In the winter of 1853, as Georgia lawmakers assembled in Milledgeville, a bill was introduced that would create a new county from a portion of sprawling DeKalb County. On December 7, on the bill’s second reading and during deliberations in the state Senate, Senator John Collier of DeKalb amended the bill to insert the name “Fulton” into the previously blank line intended for the county’s name. With this action, and with the approval of Governor Howell Cobb on December 20, 1853, Fulton County was officially born.

But a curious question arose in Atlanta’s historical community in 1932: for whom was the county named?

For close to eighty years, the prevailing assumption—one taught in schools and published in official state histories—had been that Fulton County was named for Robert Fulton, the famed inventor of the commercial steamboat. Fulton’s 1807 voyage up the Hudson River aboard the Clermont secured his place in American lore. Georgia, deeply connected to international trade and coastal commerce, had reason to admire the man whose steam-powered innovation promised new possibilities for travel and freight, however upon closer examination it does seem a bit strange to honor Robert Fulton when a Georgian – William Longstreet – had been experimenting with steam navigation going back to 1788 when he received the first and only patent issued by the state of Georgia for applying steam to navigation (patents were issued by the states under the Articles of Confederation and prior to the adoption of the U.S. Constitution in 1787. The first U.S. patent was issued in 1790). It’s also important to note that Longstreet made a successful trip on the Savannah River two days prior to Robert Fulton’s journey into fame and history with the Clermont.

You can see my article regarding William Longstreet here.

As early as 1932 James W. Mason (1871-1957), attorney and historian and Walter G. Cooper (1860-1939), a journalist, historian, civic and religious leader, challenged the Robert Fulton namesake narrative. Cooper included Mason’s take on the matter in his book, Official History of Fulton County (1934). Stephens Mitchell (1896-1983), an attorney, historian, and brother of the author, Margaret Mitchell, also publicly raised doubts about the Robert Fulton tradition in 1932, citing Mason’s belief that Hamilton Fulton, not Robert, might be the true namesake.

It doesn’t surprise me that the name Hamilton Fulton is new to most people. He seems to be historical footnote regarding the history of Atlanta area. Even so, that doesn’t make him any less important.

Hamilton Fulton was born on May 26, 1781, in Paisley, Scotland, an area best known for the Paisley cashmere shawls many women wear including myself. He was the son of a grocer named Hugh Fulton (1759-1825) and became a civil engineer of some fame both in Britain and in the United States working for a time in North Carolina and Georgia. His early work began in the Scottish Highlands and North Wales with well-known engineers, John Rennie and Thomas Telford, surveying roads. Between 1809 and 1810 Hamilton Fulton worked on projects in Sweden and completed a survey of the Stamford Canal. In 1815, he was commissioned by the British Admiralty to travel to Bermuda to report on naval constructions at the Ireland Island dockyard. Two years later he was doing the same thing in Malta.

At some point Hamilton Fulton and Peter Brown, a successful attorney and member of North Carolina’s legislature crossed paths. Brown was interested in internal improvements and traveled to Great Britain in 1818 seeking a qualified man to serve as North Carolina’s chief engineer. Fulton accepted the position enthusiasm and moved to the United States with his wife and children.

Fulton’s duties in North Carolina included improving the navigability of the state’s waterways alongside his assistant surveyor, Robert H.B. Brazier. Notes posted at Fulton’s Find-A-Grave webpage state his “focus was on practical improvements for navigation, not for steamboats but for flat boats that could carry produce from river landings to points of shipment. He deemed rivers like the Catawba and Yadkin navigable almost to the mountains and proposed the reopening of Roanoke Inlet, which had been closed since 1795. Fulton’s recommendations were meticulous, reflecting his understanding of the necessity to preserve natural vegetation and employ natural and mechanical forces to maintain an open inlet. His reports conveyed his skill and understanding, and although the Roanoke Inlet project did not come to fruition, his plans remained the basis for state planning for the next twenty years.”

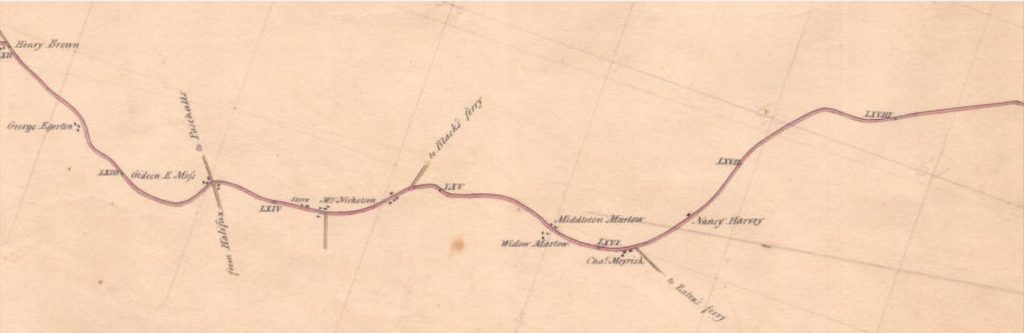

The North Carolina State Archives have many of the survey maps Fulton created mounted on linen in his capacity as state engineer. I share below a close-up section of one survey he completed in 1822 showing “The Plan of the Stage Road from Fayetteville [North Carolina] to Raleigh.”

North Carolina wasn’t the only state interested in internal improvements. The Georgia legislature created a Board of Public Works in 1825. The seven-man board consisted of George M. Troup, Georgia’s governor at the time, as well as Wilson Lumpkin and James H. Couper. The board’s mission was to explore ways to improve the state’s internal transportation infrastructure, whether through roads, canals, or railroads.

Today, we mainly remember Wilson Lumpkin for his term as Georgia’s governor from 1831 to 1835 when the remaining Creek and Cherokee lands were ceded to Georgia and tribe members were removed west to the Indian Territory, but as early as 1818 and again in 1821 Lumpkin oversaw running the survey lines for territory ceded by the Creek Nation following service as a state representative for Clarke County.

James H. Couper (1794-1866) was a man of many interests. He was an archaeologist, geologist, an architect who designed the present-day Christ Church in Savannah on Bull Street and was a contractor for the Brunswick Canal, historian, and plantation owner including Hamilton, Cannons Point, and Couper’s Point on St. Simons Island and Hopeton on the Altamaha River.

During Governor Troup’s annual message in 1826 he announced the appointment of Hamilton Fulton as Georgia’s Chief Civil Engineer calling him “a gentleman of renowned integrity of character.” In his book The Removal of the Cherokee Indians from Georgia (1907) Wilson Lumpkin would say of Fulton, “He had seen more, read more, and knew more, upon all the subjects pertaining to his office than [Governor Troup] and all the board put together.”

The top agenda item for the Board of Public Works was to provide a system of internal improvements for Georgia including the feasibility and/or construction of canals, railroads, and roads across the state. The board planned two projects that would cross the state. The first would reach from Tennessee to the Atlantic Ocean, and the other would begin at Savannah and head inland to the Flint River. Two surveying parties were formed to travel through the area, conduct surveys, and return to the Board with recommendations if the landscape was feasible for canals or railroads.

Hamilton Fulton and Wilson Lumpkin worked together to lead a survey party charting a route from the Atlantic Coast to the Tennessee River, passing directly through the region that would later become Fulton County. This included some settled portions of the state as well through portions of the Cherokee Nation, but overall, the land they surveyed was a vast and often harsh wilderness. Fulton and Lumpkin’s survey was no small feat. It required immense logistical skill and endurance.

Fulton was the first to advocate for railroads over canals in Georgia – an idea revolutionary for the time, when railroads scarcely existed, and canals were the dominant model of internal improvement. The Erie Canal had been completed the year before and there were scarcely twenty-two miles of railroad in the entire world!

Lumpkin wrote in his book, “After laborious and instrumental examination of the country from Milledgeville to Chattanooga, it was the opinion of Mr. Fulton and me that a railroad could be located to advantage between the two points above named, but that a canal was impractical. It is a very remarkable fact, too, that the route selected by Mr. Fulton and me, a large portion of it then in an Indian Country, and but little known to civilized men, should in its whole distance have varied so slightly from the location of our present railroads now in operation.”

James H. Couper had been wary of railroads along with other members of the Board of Works, but after hearing Fulton’s full recommendations and seeing Governor Troup was leaning towards railroads, he supported the Board and “recommended the abandonment of the system of canals and trial, on a limited scale, of railroads as a substitute.” It is interesting to note, however, that Governor Troup balked at the idea of steam-powered locomotives and declared he could only support horse-powered railways. Still, he reported to the state legislature saying, “It need not excite surprise, if, before a long time, with the exception of the level alluvial country, the rail will universally supersede the canal, having the advantage of cheapness, expedition, healthfulness, safety and certainty.”

In his History of Atlanta (1934) and citing sources such as Edward J. Harden’s Life of George M. Troup (1859) and Phillip’s History of Transportation in the Eastern Cotton Belt to 1860 by Ulrich Bonnell (1908) Cooper says, “These men were ahead of their time, for the canal era was then at the height of glory and the railroad era lay in the future. The Board was abolished in 1826 as public opinion was not yet prepared to support a railroad program.”

Hamilton Fulton continued working as Chief Engineer of Georgia. He prepared plans for the enlargement of the old Capitol, at Milledgeville, and oversaw this work in 1827-1828, but despite his visionary work, Hamilton Fulton’s tenure in Georgia was short-lived. The bitter political rivalry between the Troup and Clark factions led to his dismissal under the administration of Governor John Clark (or Clarke depending on the source), and he faded from public life in Georgia soon after 1828. He continued to influence engineering in Great Britain through the early 1830s until his death in 1833.

Hamilton Fulton’s life work stands as a testament to the impact thoughtful and sustainable engineering can have on society’s progress.

Hamilton Fulton rests in the churchyard at St. John the Evangelist, a church known locally as St John’s Waterloo. It was built between 1822 and 1824 on swampy ground close to the Thames River in the Waterloo section of London on Waterloo Road. There are 110 graves in the churchyard at St. John’s, the most famous being William Godwin, Jr. (1803-1832) who tragically passed early in his writing career due to a cholera epidemic. He was the stepbrother to Mary Shelley (1797-1851), author of the Gothic novel, Frankenstein.

It is important to remember that the survey work completed by Hamilton Fulton and Wilson Lumpkin set the stage for later development in Georgia – a system upon which Atlanta and, by extension, Fulton County, would eventually be built. The Georgia General Assembly voted in 1836 to construct the Western & Atlantic Railroad. It would generally follow the same route of Fulton and Lumpkin’s survey completed ten years prior. Present-day Atlanta was the site chosen as the southern end of the rail line – the terminus – and between the years 1841 and 1843 following his years as Georgia’s governor, Wilson Lumpkin worked with the Western & Atlantic Railroad. It was during this time, in 1842, Lumpkin was approached by prominent men who wanted to name the little village that had sprung up at Terminus for him due to the work he had done with the state’s Board of Public Works. At that time there was probably thirty residents and six buildings including a two-story brick depot. Lumpkin was honored but asked the delegation to name the little village for his youngest daughter instead, so on December 23, 1845, the little village became Marthasville. It was a name that stuck until 1847 when the growing rail hub became known officially as Atlanta.

It could be argued that some sort of perpetuation of Hamilton Fulton’s name would be fitting as well, but I have found no proof. Governors Troup and Lumpkin and James H. Couper were still living in 1853 when the Fulton County legislation was moving through the legislature, and it may be that Senator Collier who introduced the legislation and eventually filled in the name “Fulton” on the blank line knew of or had been told of Hamilton Fulton’s great service to the state and so perpetuated his memory. Perhaps he wanted to honor the overlooked engineer who had first envisioned the transformation of the area where Atlanta sat from vast wilderness to the railroad hub of the South.

This was basically the crux of James W. Mason’s argument supporting the Hamilton Fulton theory. He asked why would a county in railroad-born Atlanta be named after a man of steamboat fame, especially when Georgia’s own rail infrastructure owed much to an engineer with the same surname?

He noted that Robert Fulton’s name had little relevance to Georgia’s internal development. Further, Robert Fulton had been associated with the infamous New York steamboat monopoly—a partnership with Robert Livingston that was struck down in 1824 by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). In this case, the monopoly was ruled unconstitutional in favor of Thomas Gibbons, a wealthy Georgian. As Mason noted, it would be odd for Georgians to honor the man who had opposed one of their own in such a critical legal matter.

Moreover, Mason emphasized that Atlanta and Fulton County owed their very existence to the railroad, not river traffic. To name the county after a steamboat inventor, when the region’s genesis was tied directly to the Western & Atlantic Railroad, seemed incongruous. In contrast, Hamilton Fulton had physically surveyed that very corridor in the 1820s, and his reports laid the groundwork for Georgia’s pivot from canals to railroads.

Yes, the perpetuation of Hamilton Fulton’s name was certainly warranted, but there is no definitive proof other than theory and conjecture.

Stephens Mitchell and Mason further observed that there is no legislative record explaining the choice of name. Senator Collier inserted “Fulton” into the bill without comment or elaboration. I’ve researched a few namesakes for various Georgia counties and the legislative timeline for the formation for them and I must note here that there is no legal requirement that the namesake has to be explained or even noted in the legislation. In fact, it would be rare. Namesake information generally can be found in newspaper mentions as the county’s legislation was filed or mention during floor discussions and speeches in the General Assembly which during this time were often published word for word in the newspapers.

Enter the definitive Atlanta historian, Franklin Garrett, to finally settle the matter regarding Fulton County’s namesake. In 1954 officials with Fulton County were planning the county’s centennial just as Garrett’s three-volume history of Atlanta and Fulton County was being published.

In his book Atlanta and Environs Garrett states, “The discussion [regarding Hamilton Fulton as the county’s namesake] had its inception in the fact that no historian or writer upon the subject could find, or had taken the trouble to cite, contemporary evidence upon the subject. And further that Hamilton Fulton appeared to be the more logical candidate for the honor.”

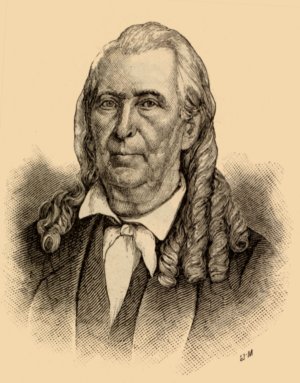

Garrett further states he leaned toward Hamilton Fulton as the honoree and was “anxious to prove it” but there was evidence to the contrary. He cites a newspaper article where Jonathan Norcross (1808-1898), Atlanta’s fourth mayor, sawmill operator and merchant, states the idea to name the county after Robert Fulton of steamboat fame came from a suggestion made by Dr. Nedom L. Angier (The Atlanta Constitution, February 5, 1896) who was also mayor of Atlanta from 1877 to 1879, but no context was provided.

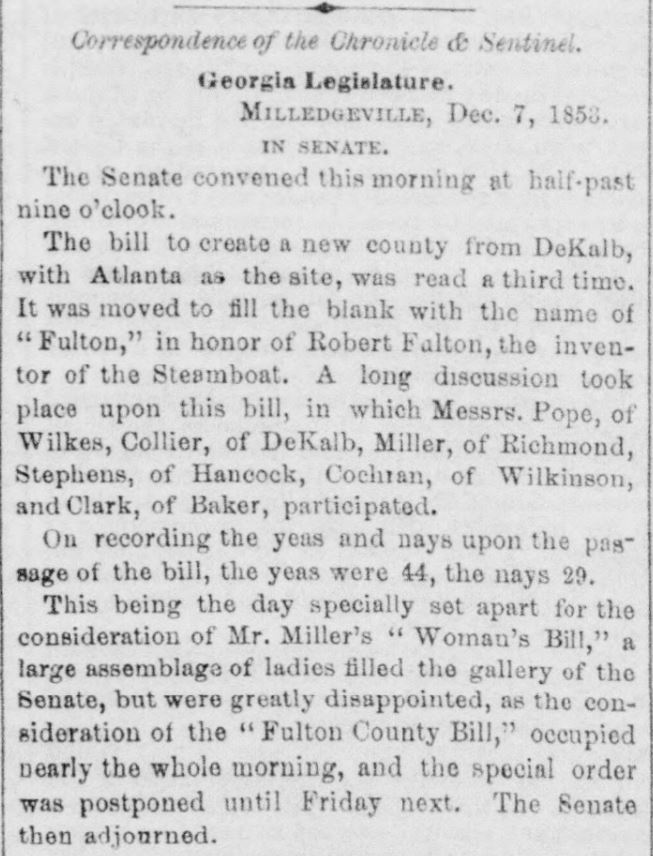

Then Garrett located the coup de grâce for those supporting the Hamilton Fulton theory. His source was a mention of the legislation published in real time during the legislation’s journey through the General Assembly in 1853.

This snippet appeared in the Daily Chronicle & Sentinel; an Augusta newspaper published December 10, 1853, which I present below. This article mentions the intended honoree for the new Fulton County.

That settles it. The honoree was Robert Fulton of steamboat fame.

With proof now in hand Fulton County officials could go ahead with creating a centennial coin – a commemorative bronze medallion featuring Robert Fulton’s likeness on one side with the dates 1854-1954 encircled by the words “Fulton County Centennial.” The back of the medal shows a simple four-columned courthouse with the words Campbell, Milton, and Fulton on its façade, naming the three counties that eventually merged to form Fulton County as it was in 1954 and today.

The coins were designed by Ivan Allen, Sr. (1876-1968), who was the president of the Atlanta Historical Society at that time and owner of one of the city’s most successful businesses. He was also the father of Ivan Allen, Jr., Atlanta’s fifty-first mayor.

Six thousand medallions were ordered.

Locating one of these medallions had been on my wish list for some time, I found one on EBAY and managed to snag it, but I must be truthful. I would rather have a medallion with Hamilton Fulton’s likeness instead, but published sources bear out Robert Fulton as the namesake of the county, so that’s that.

I took my own investigative journey a few years ago documenting the history behind the namesake for Douglas County due a perpetual myth that a group of ex-slave owners and ex-Confederates had named a new county in Georgia during Reconstruction for Frederick Douglass. You can follow the journey through my research here for the outcome.

Leave a Reply