If I asked you to name for me some of the locations of Civil War battles I’m fairly certain you wouldn’t mention Port Hudson, Louisiana in your top five, but the events that surround that place represent an important pivot point in the Civil War. The siege that took place there in 1863 is still on the record books at the longest siege in military history from May 22 to July 9, 1863. It was only after Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, 1863 that Port Hudson succumbed five days later. The surrender at Port Hudson resulted in the Union finally controlling the length of the Mississippi River and split the Confederacy in two.

The town of Port Hudson sits atop 80-foot bluffs overlooking a hairpin curve along the Mississippi River. The cities of Memphis and New Orleans had fallen to the Union in the spring of 1862. Confederate leaders knew it was vital they kept the remainder of the river in their control.

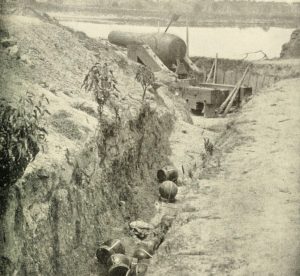

General P.G.T. Beauregard, of Fort Sumter fame, was one of the first to notice the topography along the river at Port Hudson would make it a perfect place to station Confederate guns since any approaching Union vessels would have to slow to negotiate the sharp hairpin curve, and he suggested large guns should be installed on the high cliffs. By the autumn of 1862 batteries placed along the bluffs would be able to command the entire river front including over 20 cannons arranged in 11 batteries of artillery and 9 batteries of heavy coastal artillery were placed along the cliffs at Port Hudson.

Ten weeks prior to the beginning of the siege at Port Hudson, Rear Admiral David G. Farragut decided to make a run past the Confederate’s river defenses and knock them out. When ground defenses which would assist him did not materialize fast enough Ferragut chose to act anyway on the night of March 14, 1863.

One of the Confederate soldiers manning a gun at Port Hudson was Henry Clay “Dutch” Bailey who following the Civil War lived out the remainder of his life in Carrollton, Georgia. In July 1898, “Dutch” Bailey, referred to as “Gunner Bailey,” gave his first-hand account of what happened that night at Port Hudson to The Atlanta Constitution.

There were seven Union vessels that approached Port Hudson that night under Ferragut’s command. Three of the Union ships – the USS Hartford, USS Richmond and USS Monongahela – were tied off to smaller gunboats so if the larger ships ran aground, they could immediately be pulled to safety. The USS Hartford served as Ferragut’s flagship.

Historical sources state Ferragut ordered several changes to the vessels to prepare them for a night attack including whitewashing the gun decks to improve visibility, using mortar boats for support, and lashed the anchor chains to the sides of the vessels to serve as armor of sorts. Unfortunately, he did not properly survey the Confederate defenses along the bluffs and greatly overestimated them.

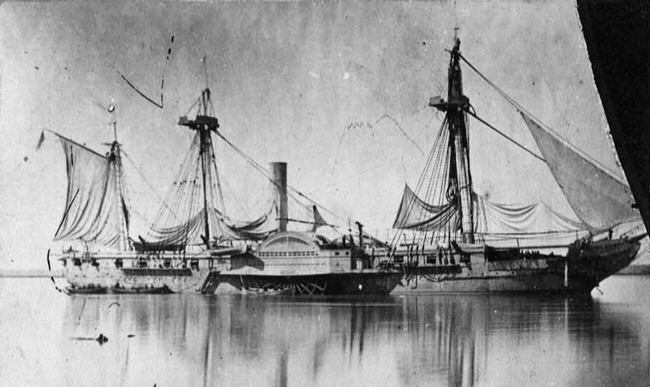

The seventh ship in the flotilla was the USS Mississippi, a steam paddle frigate. Due to the large side-wheel paddle boxes she was not tied off to another vessel. The Mississippi had quite a history prior to the Civil War seeing action during the Mexican American War, and in the early 1850s sailed for Japan as part of Commodore Perry’s expedition to open trade with Japan.

According to Gunner Bailey’s first-hand account the first vessel that approached Port Hudson was the Mississippi. The boat was first sighted when within five miles of the port, but the range of the guns was only four miles and Bailey waited for the boat to get within range before firing.

“As the Mississippi came up,” Bailey said, “I began to pour solid shot into her water line. The engagement lasted only 32 minutes, but I fired exactly sixteen shots from my gun. When the boat was within one mile of my gun, I sent a shot that crashed through her center and wrecked the machinery below, crippling her engines and running her aground on the other side of the river. Before the boat could be put into shape to get into the channel we threw hot shot and combustible shells into her and she burned to the water’s edge in full view of the battery. “

The Mississippi’s crew swam ashore. Bailey related, “We sent out boats, but captured only four of the crew, as the others ran ashore, ran down the other side of the river and were taken on board the other ships of the fleet, which then returned, never again daring to pass us.”

Historical accounts mention the Confederate garrison at Port Hudson cheered as the ship went up in flames and at one point drifted loose from the shore around 3 a.m. and floated back down river sending panic through the remainder of the Union fleet. They knew the ship’s magazine could explode at any minute, and it eventually did explode at 5 a.m. The blast was so powerful it was seen in New Orleans 80 miles away.

One of the men who escaped from the USS Mississippi was Lieutenant George Dewey who would gain fame as the admiral who would sink the Spanish Pacific fleet in Manila Bay during the Spanish American War. That fact wasn’t lost on the Constitution’s reporter as he interviewed Gunner Bailey and asked him about Lieutenant Dewey.

Bailey answered he was certain Dewey used some of the experience he had learned on the Mississippi River that night in 1863. Bailey said, “If I could just get to Manila and see Dewey, I think I could show him several new points about the firing of a rifle. There is no doubt but that he would remember me and in five minutes I could refresh his memory exceedingly. Lieutenant Dewey was brave man during the action, and he steered his boat full into the channel of the river and approached our fort with colors flying, the men cheering and every gun on deck firing point blank at us. We did not lose a single man and not one of us were even injured.”

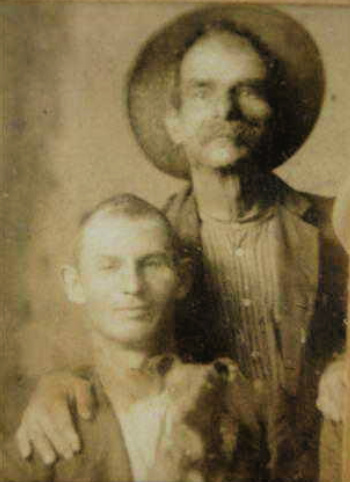

Henry Clay “Dutch” “Gunner” Bailey was born in Alabama on January 31, 1846, the son of Alabama pioneer Foster Bailey (1805-1881) and Susannah (McKensie) Bailey (1805-1870). Bailey was married to Melissa Ann (Miller) Bailey and had five children. Census data indicates he worked as a carpenter, well digging, and blasting.

Bailey also ran for Coroner of Carroll County as early as 1894 and may be been coroner when he was interviewed by the Constitution in 1898. Bailey’s war service cost him the hearing in one ear. and he suffered from hernia due to moving cannon and other large guns. No longer able to work by 1903 due to his injuries he applied for an indigent pension before finally passing away in 1911.

Bailey’s obituary in the Carroll Free Press for January 12, 1911 stated he died at his residence on West Chandler Street in Carrollton after a sickness lasting several months. He was remembered as a warm-hearted man with good character, and now we know he was the man who helped sink the USS Mississippi one March night in 1863.

If you enjoyed this true history tale you will like my latest book – Georgia on My Mind: True Tales from Around the State which contains 30 true tales from all around the state including three stories from Atlanta, and yes, there will be volume two out soon! You can purchase the book here…in print and Kindle versions.

Enjoyed the article very much as native Atlanta person it was interesting to see the service of our Southern patriots. I have a personal interest in Douglas and Cobb Counties. My ancestors had great part and building of Marietta.