During World War II a Liberty Ship was named for him. His name was attached to an underground newspaper in Madison, Wisconsin, and a group of journalists named their wire service for him. A school in the Bronx in New York City carries his name complete with a ten-foot-high limestone statue of his likeness, but I’m guessing that reading this web article might be your first introduction to Peter Zenger (1697-1746) unless you are a Constitutional lawyer, historian, or scholar.

Peter Zenger came to the American Colonies in 1710 with his family as part of a large group seeking freedom and new opportunities from the German Palantine. The Palatine was a historical region going back to the Holy Roman Empire which lasted from the year 800 to 1806. Through the 1600s and 1700s the Palatine area was repeatedly devastated due to invasions and war. Thousands of Palatine refugees headed to Great Britain and then to the American colonies. Zenger’s family cross the Atlantic with a large group of German Palatine immigrants that filled ten ships provided by the British government.

Unfortunately, the voyage for the Zenger family was marked with sickness and tragedy. Peter’s father was one among many who died in during the crossing. The arrival of hundreds of immigrants was no surprise to then New York governor, Geradus Beekman (1653-1723). He had been alerted by the British government, and a series of tents along the Hudson River was waiting on the immigrants as their first home. Zenger and his family were eager to find out who they would be assigned to for their indenture contract or apprenticeship to pay the fees incurred for their passage to New York.

Many people undertook the journey to the early American colonies by agreeing to be indentured servants or serve apprenticeships. Many entered these agreements because the person they worked for agreed to pay for their travel and other expenses. The new immigrants would agree to work for terms lasting from three to ten years with most lasting seven years. While the immigrant had no choice regarding who they worked for and some people were harsh and took advantage of the immigrant in various ways, the immigrant was able to learn a trade to support themselves.

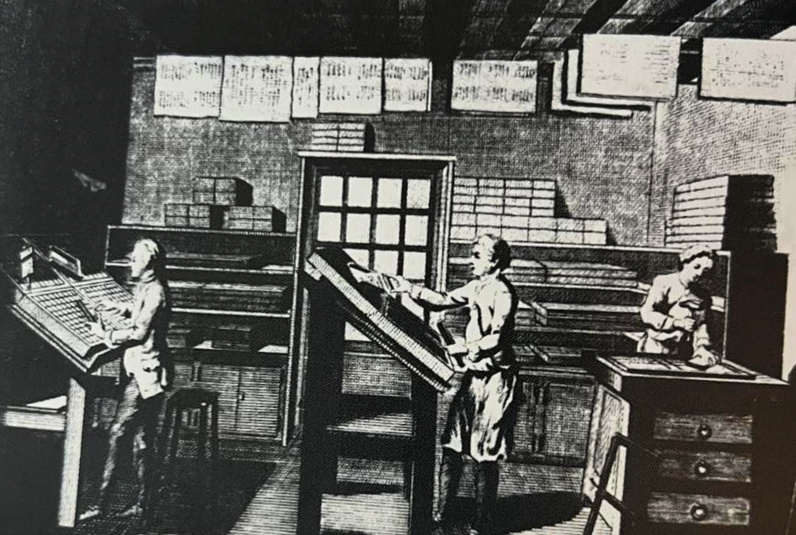

Peter’s mother and sister went to work in a Dutch household helping with the housework as indentured servants. John Zenger, Peter’s brother, was apprenticed to a carpenter, and Peter was apprenticed to William Bradford (1663-1752), a printer. He’s also remembered as the first printer in New York in 1693 after establishing the first printing press in Pennsylvania in 1685.

Zenger completed his apprenticeship with Bradford learning the printing trade during the day and completing school work with Bradford’s wife in the evening. The apprenticeship ended when Zenger turned twenty-one. He would set up his own shop for a short time in Maryland but would return to New York and partner with Bradford in 1725. That same year Bradford began publishing The New York Gazette, a royalist newspaper which was a mouthpiece for both the British and New York government. Bradford’s paper never published a dissenting word against local government or the British King.

Zenger would soon set up his own print shop on Smith Street in New York City.

King George II appointed a new governor, William Cosby (1690-1736), for New York on January 13, 1732. Thirteen months would elapse between the time Cosby was appointed and the time he arrived in the New York colony. During those months Rip Van Dam (1660-1749), senior man on the colony’s council stepped in as interim governor per the custom at that time.

William Cosby’s bad reputation preceded him even though Bradford’s paper printed glowing reports regarding the newly appointed governor. Cosby’s previous appointment had been on Menorca in the Balearic Islands, an archipelago in the western Mediterranean where he had illegally seized a Portuguese ship carrying a cargo of snuff hoping to sell the cargo for his own benefit.

Once Governor Cosby arrived in New York City, he began causing issue after issue including wrangling with the colony council over the fees that had been paid to interim Governor Van Dam. Cosby demanded Van Dam turn over half of the fees he had earned as interim Governor. Van Dam refused, and the legal case ended up being heard by New York’s Supreme Court. In a vote of two to one the court ruled for Governor Cosby.

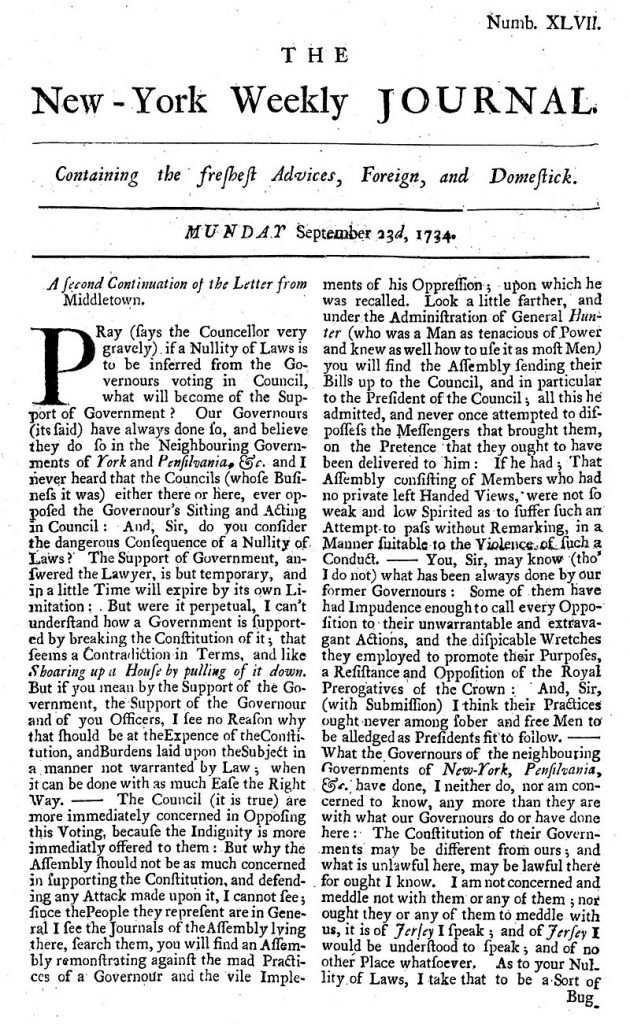

Chief Justice Lewis Morris (1671-1746) providing the dissenting opinion which he printed in full in The New York Weekly Journal along with an explanation letter saying, “If judges are to be intimidated so as not to dare to give any opinion, but what is pleasing to the Governor, and agreeable to his private views, the people of this province who are very much concerned both with respect to their lives and fortunes in the freedom and independency of those who are to judge them, may possibly not think themselves so secure in either of them as the laws of his Majesty intended they should be.”

When Governor Cosby read what Morris had to say he upset, and he was livid once he saw that Morris had printed his opinion and further explanation in a newspaper. In retaliation Governor Cosby removed Morris from the court and replaced him with a Royalist, James De Lancey.

The New York Weekly Journal where Morris printed his opinion had been established by Morris and some of his friends including Rip Van Dam and two attorneys – James Alexander and William Smith. Peter Zenger agreed to print the paper beginning in 1733. The paper gained a large following and gave rise to the Popular Party which disliked Governor Cosby’s harsh actions and wanted more freedom for colonists.

The men behind The New York Weekly Journal wanted to give the citizens of New York another view regarding the King, Parliament, and the Royal Governor of New York. They did this by submitting anonymous articles to the newspaper and sometimes used fictitious pen names. The New York Weekly Journal was like a newsmagazine full of news regarding world events as well as events in all the American colonies. The paper also included what some historians describe as “spicey articles” where no one was spared the Popular Party’s version of the truth including stories that accused Governor Cosby of taking bribes, stated he took land away land from the legitimate owners, and committed election fraud. He gave salaries for life for his Royalist cronies, and totally ignored his duties to continue to forge good will with Native Americans.

If you do a bit of investigating you can find all these instances in Cosby’s history. Historians have related how Cosby had no sense of humor, constantly retaliated against people who disagreed with him, and he’s remembered as the most oppressive governor in the thirteen colonies.

Governor Cosby made charges of seditious libels twice against Peter Zenger for printing The New York Weekly Journal. The grand jury refused to indict Zenger the first time. During the second incident the attorney representing Governor Cosby said, “just by reading the articles, you could tell they were libels.” Again, members of the grand jury sided with Zenger infuriating Governor Cosby even more since the paper continued to print with more stories exposing his actions.

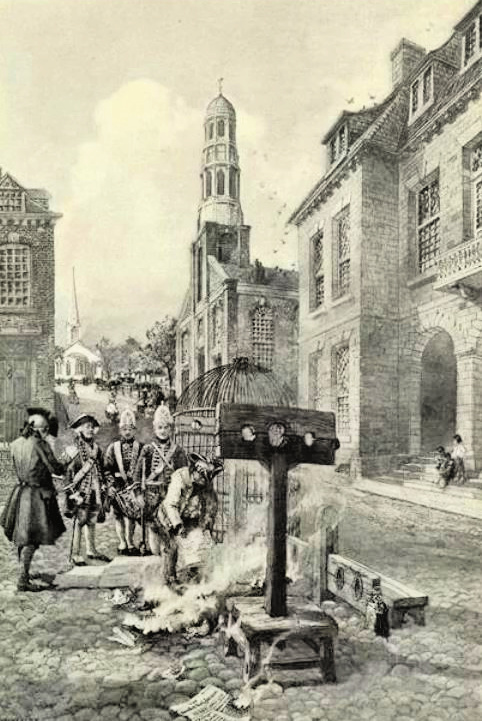

On November 6, 1734 Governor Cosby ordered copies of The New York Weekly Journal to be burned. In a proclamation the governor condemned the newspaper calling it “scandalous, virulent, false, and [full of ] seditious reflections.” He also offered a reward of fifty pounds to anyone who revealed the identities of those who was writing the articles published in the paper.

Cosby offered a reward of fifty pounds to anyone who revealed the identities of those who submitted to the paper.

This was followed by Zenger being arrested under a warrant of the council on November 17, 1734. Again, the charge was printing seditious libels. Zenger would spend a total of eight months in jail imprisoned in the attic of City Hall on Wall Street. The building was later demolished, but the present-day Federal Hall stands on the same spot. Zenger’s wife continued to print the paper in his absence.

Governor Cosby’s retaliation knew no bounds. In the days leading up to Zenger’s trial his machinations made sure Zenger’s two lawyers – James Alexander (1691-1756) and William Smith (1697-1769) – who both had submitted articles to The New York Weekly Journal – were disbarred from practicing law.

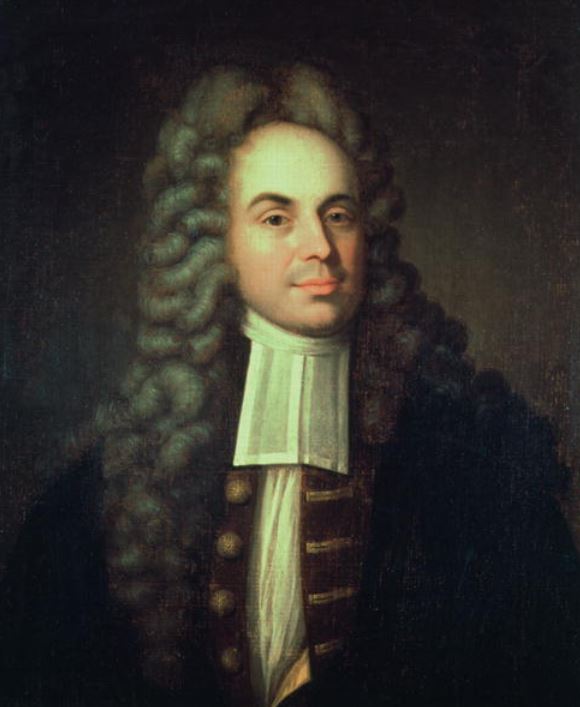

Today, if you are found guilty of a libel charge you might be accessed with monetary damages, but during colonial times under British law Zenger could have been jailed. Just when it looked impossible for Zenger to succeed someone suggested a Philadelphia attorney by the name of Andrew Hamilton (1676-1741) to defend him. Hamilton was friends with Benjamin Franklin and William Penn, and many knew he was a very capable man.

Today, to provide guilt for libel, you must have published something you know to be lie, and the lie provides injury or harm to the person’s reputation. For example, if you publish someone is a thief and they lose their job because the boss reads it, you could be charged with libel. However, in the eighteenth-century libel laws weren’t very clear.

Zenger had printed nasty things about the governor, but most people thought these things were true, however the prosecutor said it didn’t matter if the things were true. Truth was no defense, he said. In those days it was bad to say something about the King, even if it was true. The prosecutor said the governor was like the king. A governor had special rights. The prosecutor also told the jury their job was to decide if Zenger published The New York Weekly Journal or not, and of course, he did. He also told the jury they were not to interpret the law or decide if there was libel. It was up to the judge to decide if libel had taken place.

Many remember Andrew Hamilton’s eloquent defense of Peter Zenger and how he countered the prosecutor by pleading the case to jury directly. Hamilton explained to those in the courtroom that juries are made up of intelligent citizens who are smart enough to matters of law as well as matters of fact.

During the trial Hamilton spoke so softly the members of the jury had to pay attention to every word he said including, “Free men have the right to complain when hurt. They have the right to oppose arbitrary power [power used without considering others] by speaking and writing truths…to assert with courage the sense they have of the blessings of liberty, the value they put upon it, and their resolution…to prove it one of the greatest blessings Heaven can bestow…”

And then Hamilton said the best thing: “There is no libel if the truth is told.”

That was it. That was the crux of the case, but Hamilton concluded by saying that the press had “a liberty both of exposing and opposing tyrannical power by speaking and writing the truth.”

Andrew Hamilton also said some words that are worth listening to today, “The question before the court and you, gentlemen of the jury, is not of small nor private concern,” said Hamilton. “It is not the cause of one poor printer, nor of New York alone, which you are now trying. No! It may in its consequence affect every freeman that lives under British government, on the main[land] of America. It is the best cause. It is the cause of liberty.”

By now you may be agreeing with me that Andrew Hamilton was a mighty fine lawyer. In fact, his performance during the Zenger trial is the reason why the term “Philadelphia lawyer” came to be since he was from Philadelphia. At one time in our history if you wanted to say someone is a mighty fine lawyer…that they are adept and clever, then you would say he or she was a “Philadelphia lawyer.”

The jury deliberated only ten minutes and found Peter Zenger not guilty on August 5, 1735. It was one of the first instances of jury nullification which occurs when the jury in a criminal trial gives a not guilty verdict regardless of whether they believe a defendant has broken the law. There are many reasons for this but in the Zenger case the jury made a statement that the laws were unjust.

Zenger’s trial marked the beginning of important differences between libel laws in England and America. Today people have more freedom to speak out in the United States than they do in Great Britain. The Zenger case helped give juries the power to decide if the law is being broken, and it remains an important tenant of American jurisprudence today though it is important for me to say that the Zenger case did not provide the legal precedent for freedom of the press, but it did lay the foundation for it.

One historian – Michael Kammen – says Cosby’s reign in New York was a period of “political awakening” in New York politics. Peter Zenger’s legal case shows this to be true with the rise of the Popular Party and the men who were behind The New York Weekly Journal.

One of the writers of the United States Constitution, Gouverneur (his name, not a title) Morris, said, “The trial of Zenger in 1735 was the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America.”

It is interesting to note an earlier legal case from 1722 involved the editor of The New England Courant and a story he printed about pirate ships. The article hinted that the legislators of Massachusetts were not interesting in catching the pirates and might be taking bribes from them. The legislators were furious and had the editor, James Franklin, thrown in jail where he remained for about a month. The newspaper continued to publish due to Franklin’s brother who was sixteen years old at the time whose name was Benjamin. Yes, “that” Benjamin Franklin.

Leave a Reply