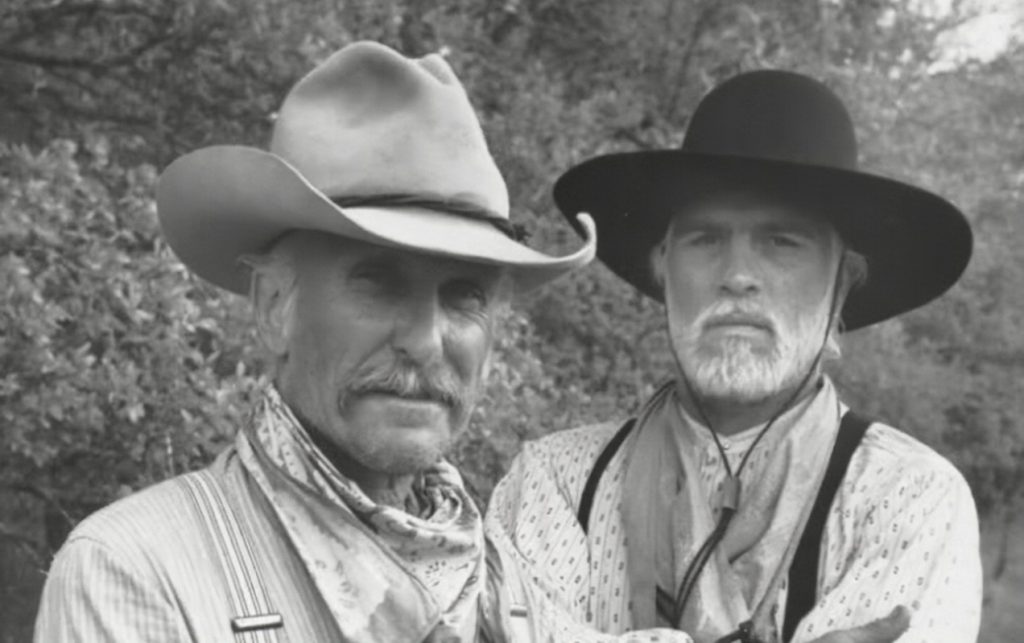

The American West is full of larger-than-life stories, but few can rival the tale of Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving—two cowboys who forged a legendary cattle trail and left an enduring mark on history. Their partnership, built on grit, vision, and sheer determination, helped shape the cattle industry and the great era of long drives that followed the Civil War.

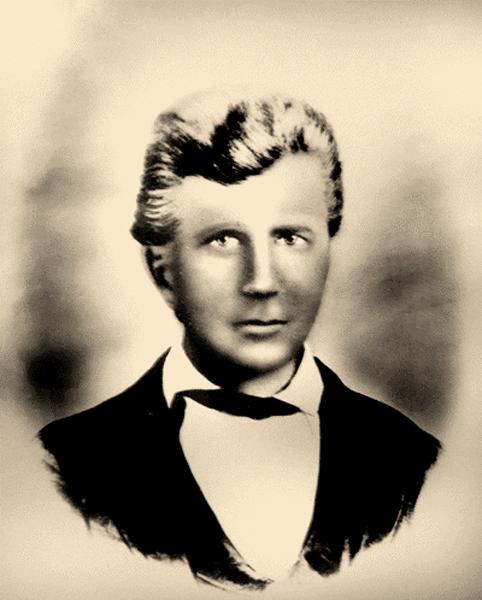

Charlie Goodnight was a pioneer with a plan. He was born in 1836 and descended from the German immigrant Hans Michael Gutknecht, making him a distant relative of President Harry S. Truman. But Goodnight wasn’t concerned with politics—he was a Texas Ranger, a rancher, and a man with a sharp eye for opportunity. He knew the land, the weather, and the dangers that lurked along the frontier, from Comanche war parties to the brutal landscapes of the Llano Estacado. And in 1866, he saw a way to turn Texas’s surplus of wild longhorn cattle into gold.

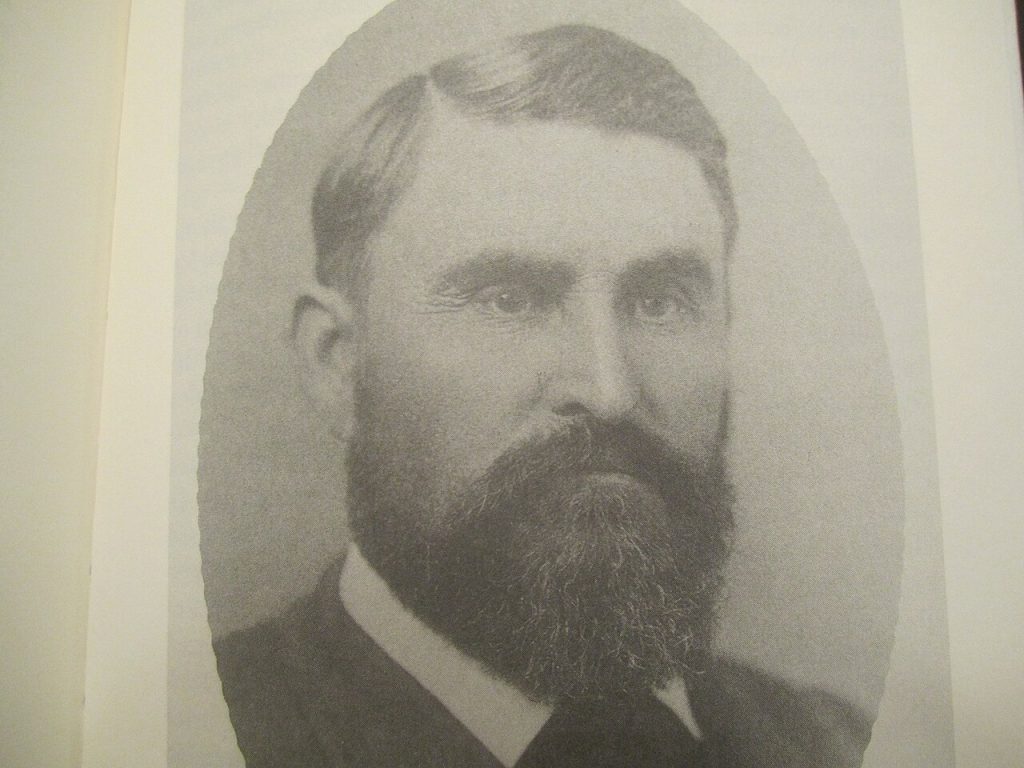

That same year, he met Oliver Loving, a seasoned cattleman who had been in Texas since the 1840s and had experience driving cattle to market. When Goodnight told Loving of his plan to drive a herd north to New Mexico and Colorado, Loving had only one response, “If you let me, I will go with you.”

Goodnight was thrilled saying, “I will not only let you, but it is the most desirable thing of my life.”

And with that, the Goodnight-Loving Trail was born.

Goodnight and Loving’s first drive can be described as going through hell and high water.

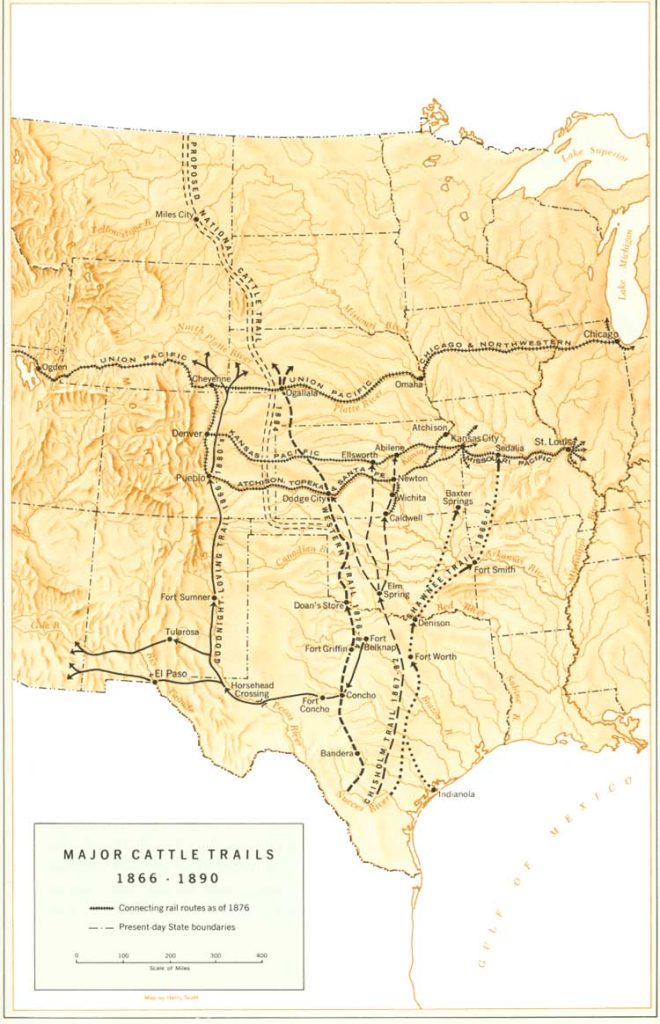

The two men, along with eighteen cowboys and 2,000 head of cattle, set out across some of the most unforgiving terrain in the West. Their trail took them across ninety miles of the arid Llano Estacado before reaching the Pecos River at Horsehead Crossing. In blistering heat, the cattle staggered forward, dropping one by one in the dust. The cowboys wrapped their faces in bandannas against the swirling grit and drove the herd relentlessly forward.

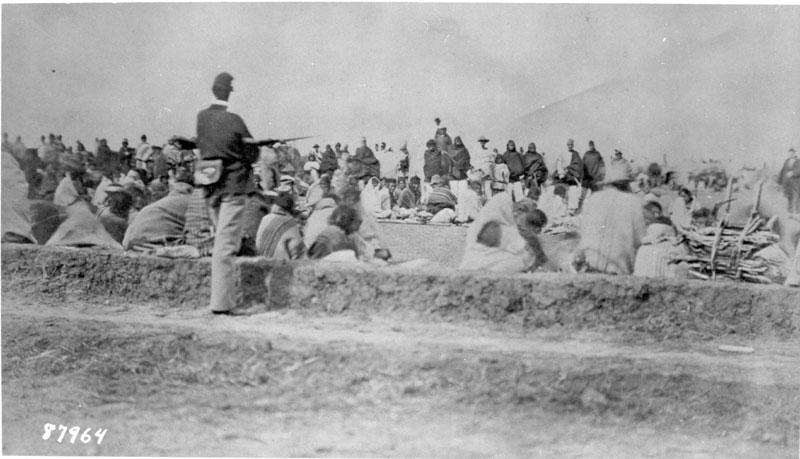

When they finally reached Fort Sumner, New Mexico, they struck gold—not in the ground, but in the form of a government contract. The U.S. Army needed beef to feed thousands of Navajos who had been forcibly relocated to a reservation there. Goodnight and Loving sold half their herd for $12,000 in gold and made plans to do it all over again.

The success of their first drive spurred Goodnight and Loving on. They partnered with legendary rancher John Chisum to supply cattle to Fort Sumner and beyond. The Goodnight-Loving Trail stretched from Texas to Colorado and eventually reached Wyoming, paving the way for countless future cattle drives.

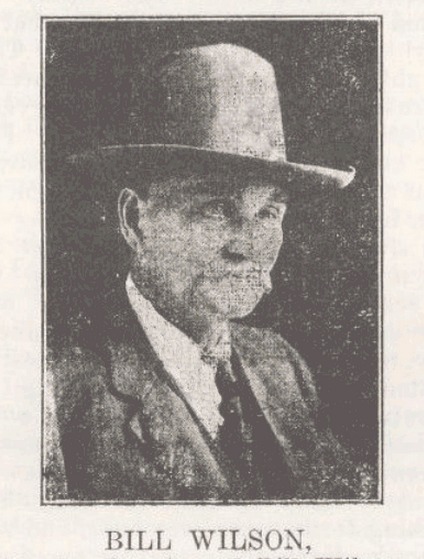

But the trail was dangerous, and on their next drive, tragedy struck. In 1867, while riding ahead to secure another government contract, Loving and his scout, One-Armed Bill Wilson, were ambushed by Comanches.

Loving was shot in the wrist and ribs but managed to escape to Fort Sumner with the help of Mexican traders. Unfortunately, his wounds turned septic. When Goodnight arrived at his partner’s bedside, Loving whispered, “I regret to have to be laid away in foreign country.”

Goodnight would hear none of it. “Have no fear about that, he promised. “I’ll take you home.”

True to his word, he packed Loving’s body in charcoal for preservation and transported it back to Texas, where Loving was buried with full Masonic honors in Weatherford’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Goodnight continued their work, driving cattle into Wyoming and helping to shape the cattle industry. He also invented the chuckwagon, a rolling kitchen that became a staple of the great cattle drives. His innovations and business sense helped define the cowboy era.

Their story has inspired countless books and films, from James Michener’s epic Centennial to Larry McMurtry’s novel Lonesome Dove (1985), which some say is loosely based on their adventures though this was denied by McMurtry.

The Goodnight-Loving Trail was more than just a path through the wilderness—it was a testament to courage, resilience, and the enduring spirit of the American West.

Leave a Reply