As far as I can tell the infamous Aaron Burr was in Georgia two different times. Burr’s first sojourn in Georgia occurred in 1804 immediately following his infamous duel with Alexander Hamilton. While the coroner was still making inquiries, Burr packed his bags and headed south. You can read about his stay along the Georgia Coast visiting people of note and riding out what is remembered to be the worst hurricane to hit the Georgia islands here.

Burr’s second visit to Georgia found him once again facing legal charges. This time instead of visiting friends along the coast, Burr was forced to travel through the wilds of western and middle Georgia under armed guard. The destination was Richmond, Virginia, and the charges were treason.

Burr was accused of attempting to use his international connections and support from a cabal of American planters, politicians, and army officers to establish an independent country in the southwestern United States. Burr’s reply to the charges was he simply wanted to farm 40,000 acres in the Texas Territory which he had leased from the Spanish Crown.

Officials stated Burr’s plans involved much more than farming, but it was difficult to know what the former Vice President of the United States was doing became he told different stories to different people.

The large tract of land the Spanish had leased to Burr was known as the Bastrop Tract along the Ouachita River in present-day Louisiana. For more background information regarding the tract of land see page 113 at this link.

Spanish ministers later recounted how Burr discussed he wanted to set up an independent nation in the Mississippi Valley. Some reported the independent nation would be in the Spanish territory in what is now Texas, California, and New Mexico. British officials were led to believe Burr’s plan would separate the states and territories west of the Appalachians from the rest of the Union and create an independent nation with Burr as its leader.

Many firmly believed the exact details did not matter at this point, but there was a scheme afoot of some sort and Burr was the instigator.

One of the men associated with Burr’s plans were General James Wilkinson (1757-1825), the first Governor of the Louisiana Territory from 1804 to 1807. Burr and Wilkinson had served together during the American Revolution and had taken part in General Benedict Arnold’s campaign to take Quebec City. It was Aaron Burr who persuaded President Jefferson to appoint Wilkinson to oversee the Louisiana Territory. By the time Wilkinson accepted the position he was a paid spy for Spain. While this was suspected at the time, it was not proven until decades after his death. Wilkinson also had a murky past having attempted to separate Kentucky and Tennessee from the Union in the 1780s.

Between 1805 and 1806 Burr corresponded with various contacts from the United States, Britain, and Spain to gain political and military support for his scheme using an island owned by Harman Blennerhassett (1764-1831) that sat in the middle of the Ohio River in western Virginia, now West Virginia. Blennerhassett offered up his island as a training and outfitting center for Burr’s activities.

Many officials at various levels left knew what Burr was up to. It was an open secret of sorts. Finally, the U.S. Attorney in Kentucky filed charges against him, but a grand jury declined to indict Burr, so he continued with his plans.

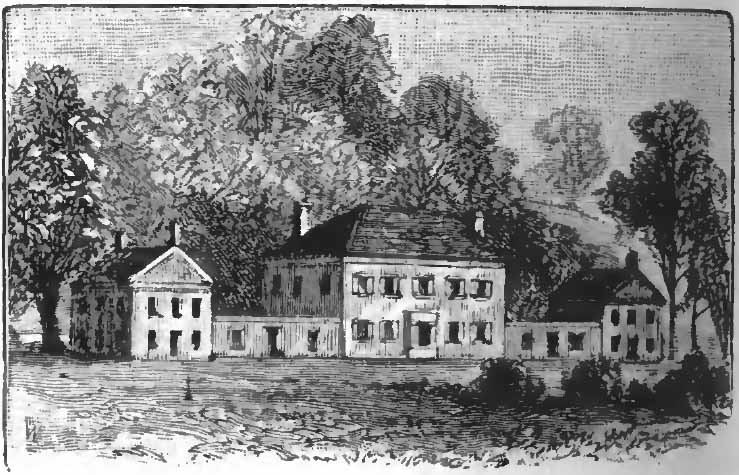

When state militias were sent to Blennerhassett’s island they seized and destroyed some of the boats Burr’s men had gathered there. The militia men took over the Blennerhassett mansion on the island where Burr had stayed in great comfort while making his plans. The home would be destroyed by fire in 1811, but a reproduction can be seen today at the Blennerhassett Island Historical State Park.

Burr and at least sixty men escaped capture by heading downriver towards New Orleans. Their hope was to begin a revolt of some sort among French settlers.

From the Georgia Republican published in Savannah for January 6, 1807 a report from Cincinnati, Ohio dated November 25th, 1806 (news travelled slowly in those days) said: Aaron Burr arrived in town on Friday evening last. On the same evening two gentlemen arrived here who informed that they had passed two boats descending the Ohio – one was a large keel loaded with French muskets; and they believed the other was loaded with ordinance and muskets. The crew spoke nothing but French during their stay on board, and that they passed every town…after night. They further mention that several large boats loaded with provisions, would shortly follow, under the command of Blennerhassett. Burr’s arriving here on the same evening, gives it rather a squally appearance.

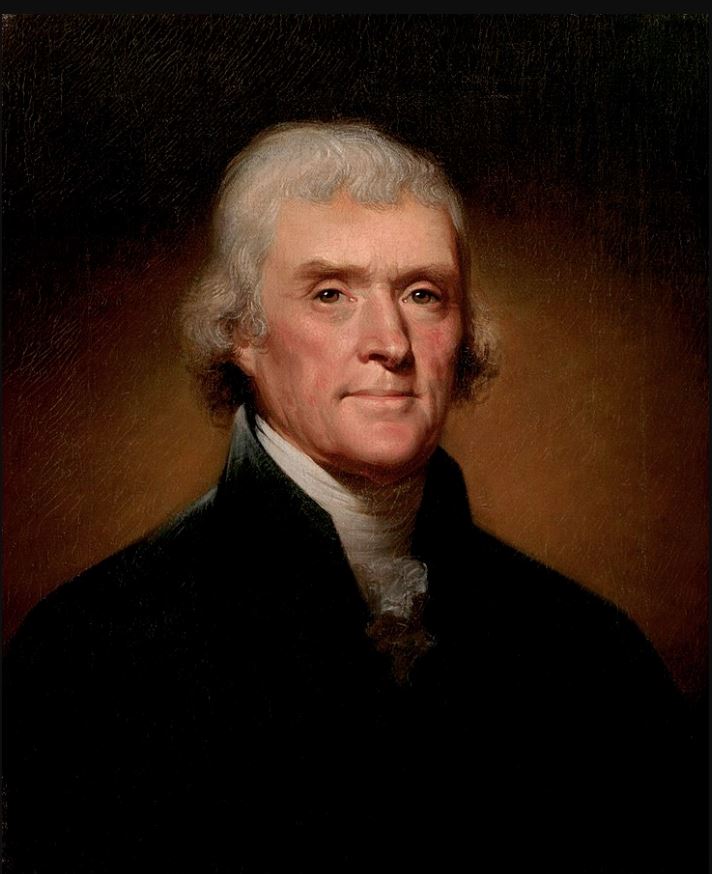

James Wilkinson, recognizing that the scheme was doomed to failure, decided to betray Burr. He wrote a letter to President Thomas Jefferson stating that Burr had “commenced the enterprise” and had secured the protection of Britain. Wilkinson described Burr’s plans as a “deep, dark, wicked, and widespread conspiracy…to seize on New Orleans, revolutionize the territory, and carry an expedition against Mexico.”

President Jefferson immediately ordered Burr’s arrest declaring him a traitor without indictment.

News of the arrest warrant and the Burr’s alleged scheme was published in newspapers across the country. By the time he reached New Orleans around January 10, 1807, Burr was aware of President Jefferson’s feelings and the arrest warrant pending against him. Burr turned himself into authorities and was examined by a couple of judges. They let the accused traitor go stating Burr’s actions had been perfectly legal.

Jefferson’s warrant remained, however, because the President was convinced Burr was a dangerous man and he wanted a conviction regardless of the evidence some sources say.

Due to the news coverage Burr’s support quietly went away and Burr fled to the wilderness along the Gulf Coast.

Federal troops caught up with Burr on the night of February 18, 1807 in an area north of present-day Mobile, Alabama near Wakefield and taken to nearby Fort Stoddert located on a bluff of the Mobile River close the confluence of the Tombigbee and Alabama Rivers. The fort served as the western end of the Federal Road which ran through Creek lands to Fort Wilkinson in Georgia. More details regarding Burr’s arrest can be found at this link.

Burr would remain at Fort Stoddard until he could be taken to Richmond, Virginia to stand trial for treason. During his stay there a Spanish officer came up the river to the fort and requested to see Burr, but he was refused.

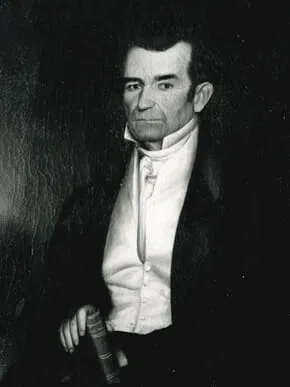

The man credited with Burr’s arrest was Major Nicholas “Bigbee” Perkins (1779-1848), an attorney, land agent, and important to Burr’s situation, a territorial militia officer.

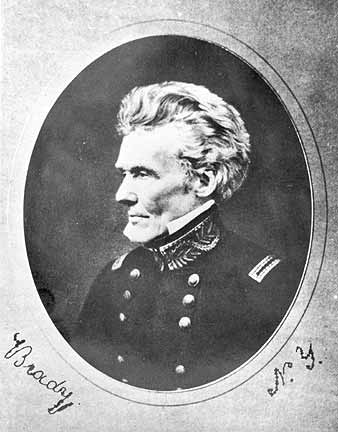

Assisting Perkins in the arrest was Lieutenant Edmund P. Gaines (1777-1849), a career United States Army Officer who was the commander at Fort Stoddart.

Perkins escorted Burr to Richmond, Virginia and both he and Gaines would later testify at Burr’s trial. The group including Perkins, the prisoner Burr, and few heavily armed soldiers set out through the wilderness with Gaines instructing them to refrain from speaking to their prisoner and not listen to anything he had to say. Finally, Burr was to be shot if he tried to escape.

During most of March 1807, the party passed through woods and swamps teeming with Indians and crossed over narrow, rutted roads, mired by chilling rain that seemed to constantly fall. The pace was grueling, covering forty miles a day on horseback. The route was chosen on purpose to avoid larger towns and villages. Major Perkins did not want Burr to have an opportunity to file a petition for habeas corpus and to avoid any altercations with citizens no matter their feelings toward the former vice president.

Little is known about the route, but we do know Burr was taken through Georgia crossing the Chattahoochee River at what is today Columbus, Georgia and ended up at the Creek Agency on the Flint River, home to the Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins. The Creek Agency was near present-day Roberta, Georgia in Crawford County. Some historians state that some of Harman Blennerhassett’s papers ended up at Hawkins’ home.

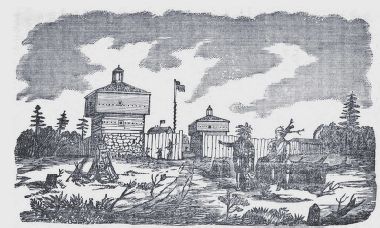

From the Flint River Burr’s captors then headed east to Fort Hawkins near present-day Macon, Georgia. It is likely that Burr was imprisoned overnight at the fort.

The fort was new having been built in 1806 as the Southeastern Command of the U.S. Army. The Lower Creek Trading Path passed just outside of the fort’s northwestern blockhouse and would later become part of the Federal Road to connect Washington, D.C. with Mobile and New Orleans.

The group crossed the Oconee River at Fort Wilkinson near the town of Milledgeville that had become Georgia’s capital city just three years earlier. The fort had been established in 1797 and had played an important role with relations between settlers and the Creek Nation. The garrison at the fort would be moved to Fort Hawkins in 1807, possibly later in the year after Burr and his guards stopped there.

There are claims including a historical marker at Warthen in Washington County that Burr spent the night in log structure there that served as the jail. Ella Mitchell’s History of Washington County (1924) says the Burr spent one night in the jail. Around 1930 newspapers began carrying her account. By 1950, a DAR marker was placed at the site, but many historians believe this to be inaccurate because prior to Ella Mitchell’s history there are no other mentions regarding Burr’s stay at Warthen. Newspapers from 1807 are quite detailed and state Burr was elsewhere during that period.

For example, the Columbian Centinel published at Augusta, Georgia dated March 21, 1807 reported from Sparta in Hancock County, Georgia (north of Warthen) that Aaron Burr “had passed through this country, about two miles miles distant from [Sparta] on Monday last, under a strong guard…”

The news report further stated, “Burr has now the same clothes on that he was taken in – a pair of course cotton pantaloons, a round coat, shoes and stockings and an old hat – having sent on his baggage to Pensacola.” The Columbian Centinel also reported that the party of men had stopped twice as they crossed Hancock County and that each time Burr experienced “execrations of his host, although they were both entirely ignorant of his being their guest” and further stated:

They stopped about twenty miles from [Sparta, Georgia] to take some refreshment, the landlord and one of the officers who accompanied Burr getting into conversation, he asked the officer, in a tone expressive of his honest indignation, ‘if he knew what had become of that [rascal] Burr and his army.’ – Burr being present replied, ‘I am the man they call Burr,’ the host rejoined, ‘Why really I did not think that he was as likely a fellow as you are.’

That night they reached the abode of an honest old farmer, about three miles from [Sparta]. Burr’s treason being almost the sole topic of conversation in the country, he enquired of the company if they could tell what had become of that fellow, he, could not tell what his name was, but he used to be next man to the President, that was trying to stir up the people against the government, because they would not give him a high enough commission. To this Burr made no reply – remembering, no doubt, the repartee he had received [that] morning.”

The group finally left the Georgia by crossing the Savannah River at Scott’s Ferry, twenty-five miles upriver from Augusta. The ferry was owned by Samuel “Ready Money” Scott, who might possibly be an ancestor stemming from my paternal grandmother, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Scott Lathem Land (1892-1964). Samuel received his nickname, “Ready Money,” because he always appeared at auctions with plenty of money and always had the high bid.

The location of the ferry is still known as Scott’s Ferry, South Carolina.

Samuel Scott, born about 1750, and his wife, Joyce or Jane (Callihan) Scott, obtained a grant of land from King George III, and settled several hundred acres of land along the Savannah River in Edgefield County.

Samuel Scott took part in the American Revolution by financing the Patriots. At one point his wife rode fifty miles on horseback to Ninety-Six to report the whereabouts of Tories and that the British were storing stolen supplies and goods on a Savannah River island. The Patriots were able to recover their goods, but in turn, the British destroyed the Scott home and outbuildings as well as the ferry. Hearing Scott might have money hidden on his property they tortured him, but he would not talk. They also put a rope around Joyce/Jane’s neck and dragged her through the Savannah River almost drowning her, but she never talked either.

During the long trek to Richmond, it is said Aaron Burr never complained along the way but did attempt to escape once, in South Carolina. Major Perkins had been concerned as the group crossed into South Carolina because he knew Joseph Alston, then a member of the state legislature, was Burr’s son-in-law, married to his beloved daughter, Theodosia. The group traveled as fast as they could through each town or village they passed in a square formation with Burr in the middle and surrounded by his guards while crossing South Carolina.

It was at Chester, South Carolina where Burr tried to escape as they rode past a crowded inn where a party was underway. Burr jumped from his horse and began crying out as loud as he could that he was Aaron Burr under military arrest and must be taken to a magistrate at once. When Burr refused to remount his horse, Perkins grabbed him underneath each arm, lifted the much smaller Burr into the air, and returned him to his saddle. One of the soldiers grabbed Burr’s reigns, and they set off as fast as they could. Once down the road it was stated Burr burst into tears. Many sources state at least one of the men in the group also had tears streaming down his cheeks faced with Burr’s humiliation.

On March 26, 1807, after an exhausting three-week journey, a wearied Major Nicholas Perkins handed Burr still wearing the same clothes he had been captured in over to the U.S. attorney in Richmond.

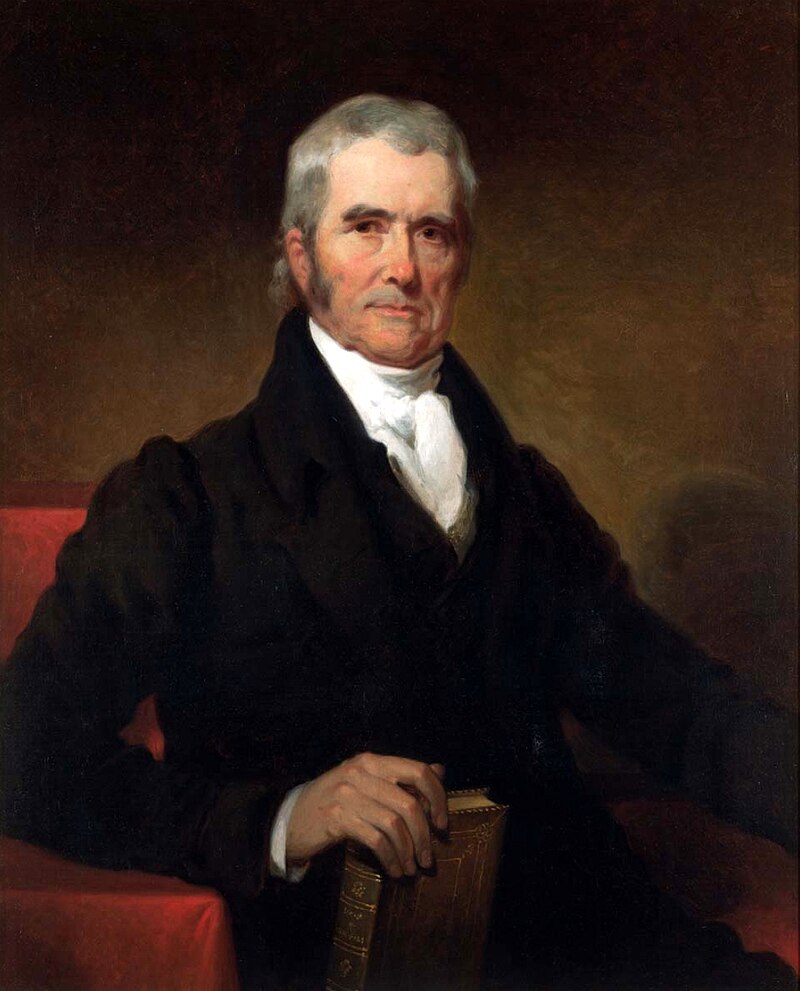

Burr’s trial for treason began four days after his arrival at Richmond with Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court John Marshall (1755-1835) presiding. It’s interesting to note that as eager as President Jefferson was to get a conviction, Marshall was equally eager to discredit President Jefferson.

During the trial Judge Marshall ruled that most of the U.S. government’s evidence against Burr was inadmissible, and he was acquitted on September 1, 1807. The reason for the acquittal was the Constitution’s very strict definition of treason as “levying war against the United States” or “giving…aid and comfort” to the nation’s enemies. In addition, each overt act of treason had to be attested to by two witnesses. The prosecution was unable to meet this strict standard. As a result of Burr’s acquittal, few cases of treason have ever been tried in the United States.

The acquittal did not improve Burr’s reputation at all. In fact, it was the final straw for many. Burr was ruined regarding his public image and any future in politics was dashed.

Following the trial Burr went to Europe, a self-imposed exile lasting four years. Not having enough money for the passage, he borrowed it from Dr. David Hosack, a friend of both Burr and Alexander Hamilton as well as Hamilton’s doctor.

Burr first went to England but was asked to leave the country when it was discovered he was making inquiries regarding support for a Mexican Revolution. Next, he went to France where even Napoleon wasn’t interested in Burr’s intrigues. Burr also spent time in Scotland, Denmark, Sweden, and Germany.

During Burr’s self-imposed exile the letters continued to flow between himself and his daughter, Theodosia “Theo” Burr Alston (1783-1813).

During her father’s exile, Theo spent her time raising money to send to her father as well as assisting him by transmitting messages to people he wanted to reach in the United States.

Burr returned to the United States in 1812 aboard a French ship and began practicing law in New York using the name Aaron Edwards (his mother’s surname was Edwards) to avoid problems his real identify might cause as well as to avoid numerous creditors.

By the end of December in 1812 Theo set sail from South Carolina aboard the schooner Patriot to reunite with her father in New York. Tragically, the Patriot was lost at sea with all aboard presumed dead. Some say the schooner was attacked by pirates or shipwrecked by a storm.

No matter the reason, Burr lost his daughter in a very tragic way.

By 1833 Burr had married Elizabeth Jumel. He was seventy-seven while his bride was in her late fifties and extremely wealthy. Her former home still stands in the Washington Heights section of New York City. The home was built in 1765 and is the oldest extant house in Manhattan.

The marriage didn’t last long. Burr’s bride secured Alexander Hamilton’s son, Alexander Hamilton, Jr., to represent her in a divorce complaining that Burr was plowing through her money at an alarming rate.

While the divorce was proceeding, Burr experienced an immobilizing stroke finally passing on September 14, 1836, the very day his divorce was finalized. He had been living in a boarding house on Staten Island named the Continental that later became known as the St. James Hotel. The hotel was located at the corner of Port Richmond Avenue and Richmond Terrace.

Burr was buried at Princeton University close to his father who was a founder of the College of New Jersey that would become Princeton and served as the school’s second president.

Aaron Burr is such a multi-faceted character in the American story. An article at American Heritage magazine states, “No one who met him ever forgot him. His charm captivated beautiful women, his eloquence moved the United States Senate to tears, his political skills carried him to the very threshold of the White House. Yet while still Vice President he was indicted for murder and was already dreaming the dreams of empire that would bring him to trial for treason. After a century and a half, historians still cannot decide whether he was a traitor, a con man, or a mere adventurer.”

What do you think?

Leave a Reply