The name Captain William Kidd or just Captain Kidd evokes images of pirates and buried treasure. Sometimes it is hard to bypass the romantic Captain Kidd and get to the real facts because he is one of those larger-than-life characters with lots of stories – some are fictional while others are just plain myth. What we do know is Captain Kidd was born in Dundee Scotland in 1645 and later settled in colonial New York City. He was a privateer or pirate depending on your point of view and which line of history you follow.

While a resident of New York, Captain Kidd had “a Turkish carpet on his parlor floor, casks of Madeira in his cellar. His house had scrolled dormers and fluted chimneys, which ships seeking New York moorage sought out as landmarks. A family man with two daughters, he owned a pew at Trinity Church” according to William J. Board of The New York Times. In his book No Man Knows My Grave, author Alexander Winston states Captain Kidd owned at least five different properties in New York City, and lived at 119-21 Pearl Street which today would be found between Wall and Hanover Streets.

Captain Kidd would lose his life to a hangman’s noose in London in 1701. Today, over 300 years later treasure hunters are still trying to track down any caches of buried treasure Kidd might have left behind.

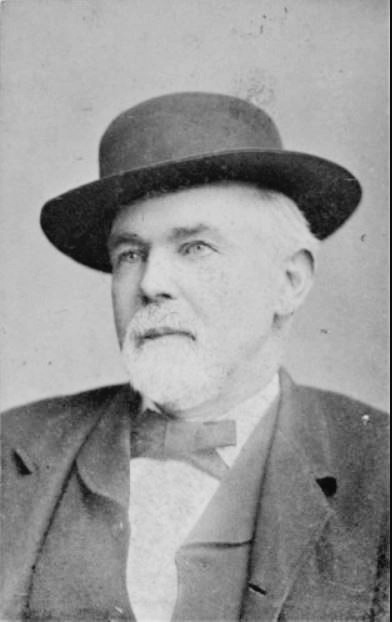

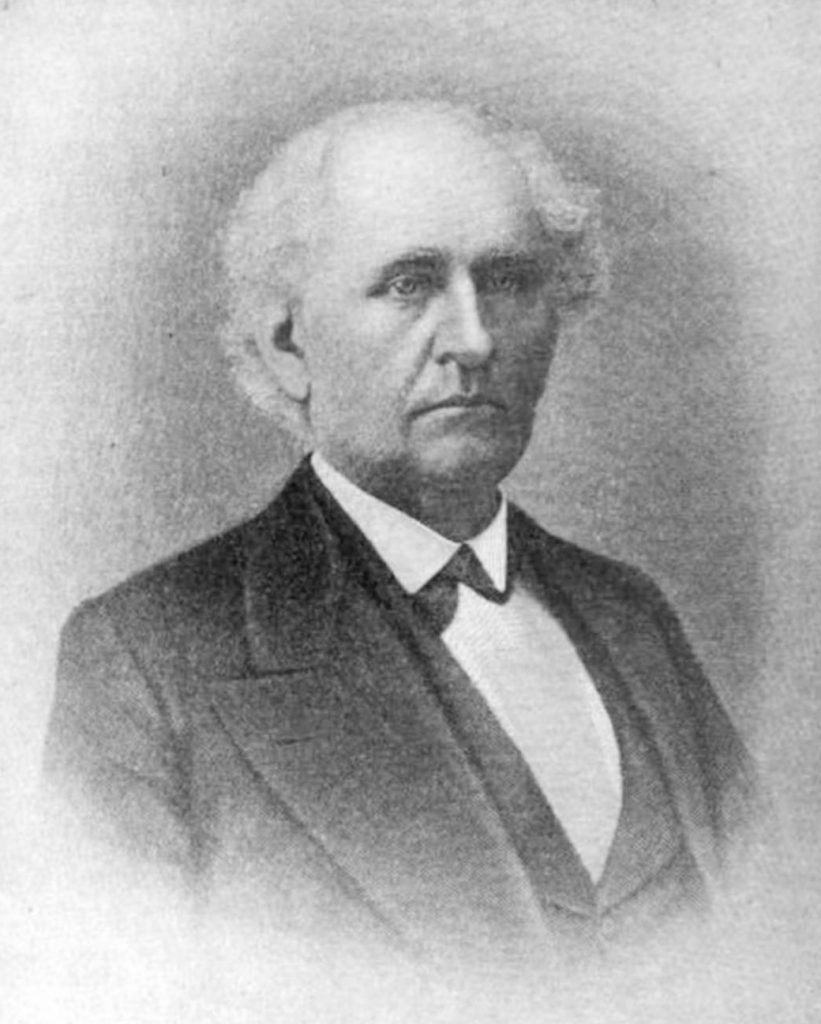

During Atlanta’s earliest days there lived a man named Captain William Kidd who was counted among the best known and most wealthy citizens, but the name is about the only similarity Atlanta’s Captain Kidd had with the privateer-pirate Captain Kidd. At the time of his death, it was stated that not only had Captain Kidd given Atlanta a land mark building, but that he was himself was a “landmark of the city.”

I would venture that there might be twenty-five Atlanta citizens today who know of Captain William Kidd and his gift to Atlanta that no longer exists, the Centennial Building, a location where Atlanta citizens pointed to with pride when discussing how rapidly the city rose from the ashes of the Civil War.

Atlanta’s Captain Kidd was born in Londonderry, Ireland in 1818 and came to this country in the early 1800s on the same ship as another pioneer Atlantan, William Rushton (1818-1881) who hailed from Manchester, England and was connected to the Georgia Railroad for many years. Kidd also found work with the Georgia Railroad as a locomotive engineer and later he took a position as a machinist. I am assuming his rank of Captain came from his involvement with Atlanta’s early volunteer fire companies since he is listed on various lists for managing the yearly Firemen’s Ball.

Kidd took some of his railroad earnings an invested in an ice business. In fact, he was the pioneer iceman in Atlanta. This business positioned Kidd on his way to becoming a wealthy man. This article from “The Atlanta Weekly Examiner” for May 1, 1856, introduced the business to the city.

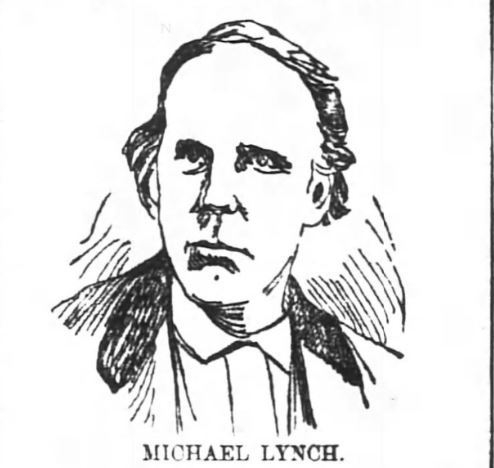

Kidd developed several different income streams. In 1862, he placed an ad looking for a suitable place for a saw mill. Later he would dabble in the book business with Michael Lynch (1825-1893). The census for 1870 notes Kidd’s occupation at that time was a book merchant. Like Kidd, Lynch hailed from Ireland arriving in Atlanta in the early 1850s. He found work at Atlanta’s only bookstore at that time owned by William Kay (1822-1859.) Though the business would change hands Lynch would eventually wind up as its owner.

Another stream of income for Captain Kidd was the grocery business with John Henry Mecaslin (1825-1906), another pioneer Atlanta citizen who was a member of Atlanta’s first fire company, an all-volunteer concern, and like Rushton and Kidd took a position initially with the Georgia Railroad. Kidd and Mescaslin would go on to purchase various properties together.

With no wife or children to provide for Captain William Kidd quickly became a wealthy man. By 1875, a list of men in the city who were paying taxes on $10,000 or more indicates Kidd remitting taxes on a little over $97,000, an incredible sum for one man just ten years after the end of the Civil War.

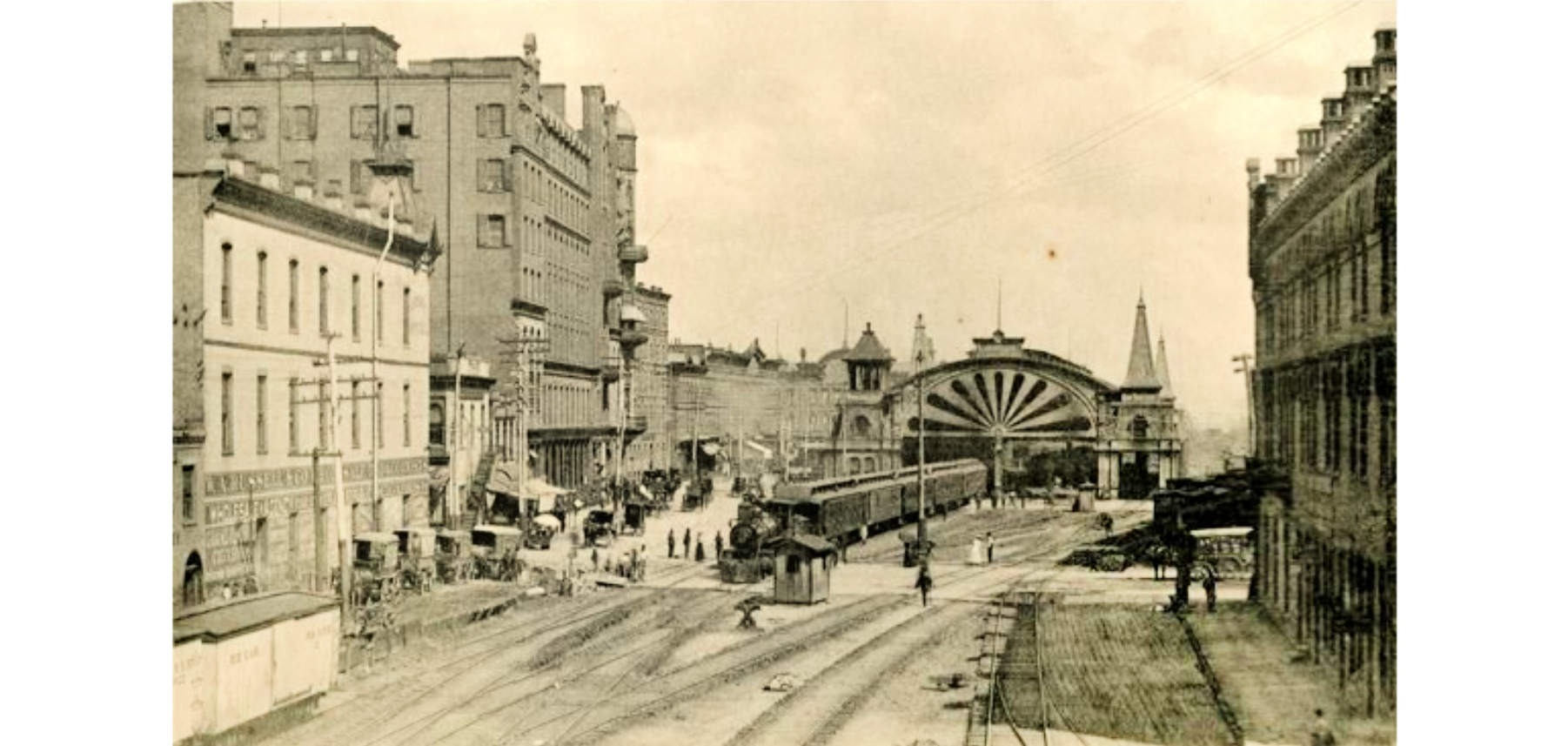

The fortune allowed Kidd the ability to build one of Atlanta’s lost landmarks – the Centennial Building located on Whitehall Street close to the Union Depot. In the image below you can see the second version of Union Depot in the middle and to your right is the Centennial Building or Centennial Block as it was often referred to in the newspapers.

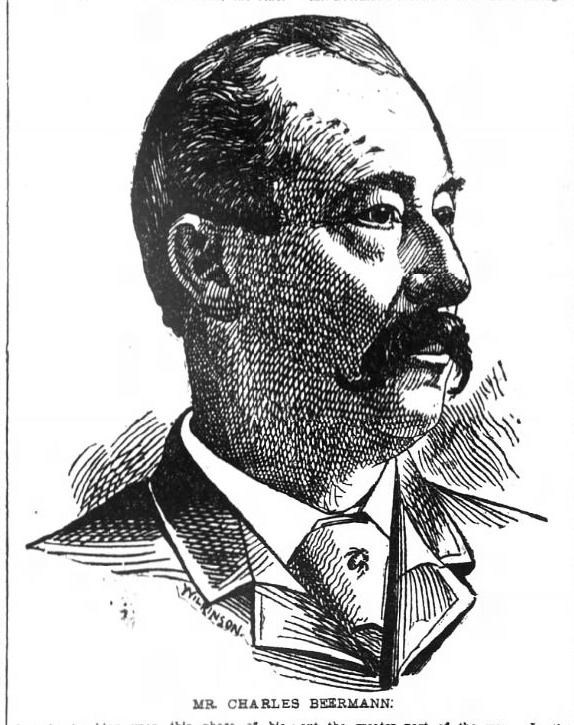

Captain Kidd had owned the property for several years having purchased it from the Georgia Railroad in the late 1840s probably for an extremely low price. He had erected what was described as “a row of shanties next to the railroad on Whitehall Street in the hasty poverty of 1865” and even then, it known to be “the most valuable property in the city.” In those early days William Kay, the bookseller, rented a small space from Kidd in those shanty buildings as did Charles Beerman (1833-1896), a German immigrant who had gotten his American start in the city of Charleston followed by Savannah and then Macon selling songbirds before reaching Atlanta in November 1858 where he established a barbershop and cigar stand. In fact, he established Atlanta’s first tobacco factory. His partner at the Kidd property next to the railroad was named Garcia, a native Spaniard. The shanty space was only sixteen by fourteen feet, but once the Century Building opened Beerman remained a tenant of Kidd’s with a new firm name of Beerman & Kuhrt. Beerman would later go on to own Atlanta City Brewing and Ice.

More than likely Kidd conceived the idea for the building’s name due to the constant news streaming out of Philadelphia regarding the Centennial International Exposition that would be held from May 10, 1876 through November 1876 – the nation’s first official world’s fair that celebrate the one hundredth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The Exposition’s main building was referred to as the Centennial Building. Another source of information involving the news coming out of Philadelphia would have been two of Kidd’s sisters – Mary A. (Kidd) Miller (1843-1904) and Rebecca (Kidd) Pigott (1824-1855) lived in Philadelphia. She was married to William Pigott an accountant and long serving armorer of the Frankford Arsenal. I do not doubt that Captain Kidd felt Atlanta should have its own version of a Centennial Building to celebrate the nation’s milestone birthday.

Kidd demolished the shanties in the Spring of 1876 and began construction on what would be known as the Centennial Block. The Centennial Building was three stories and at the time of Kidd’s death was described as a “magnificent brick building” and was “one of the best constructed buildings in the city with an iron front and conveniently arranged to afford every room ventilation and light.”

The building contained five storefronts carrying the addresses of 1,3,5,7, and 9 Whitehall Street. There were also twenty-seven offices and room, and one large hall with three rooms attached.

Some of the first tenants of the Centennial Building in October 1876 were Beerman & Kuhrt (mentioned above) in the corner location and the Lynch & Thornton bookstore was above it.

Michael Lynch (mentioned above) was one of the partners in the bookstore and was Captain Kidd’s longtime friend and former partner. The middle store was rented by the clothing store of M & J. Hirsch which was a second location for them. Another early tenant was the real estate firm of Marcus A. Bell & Son. I’ve written about Marcus A. Bell and his home known as the Calico House, another of Atlanta’s lost landmarks here.

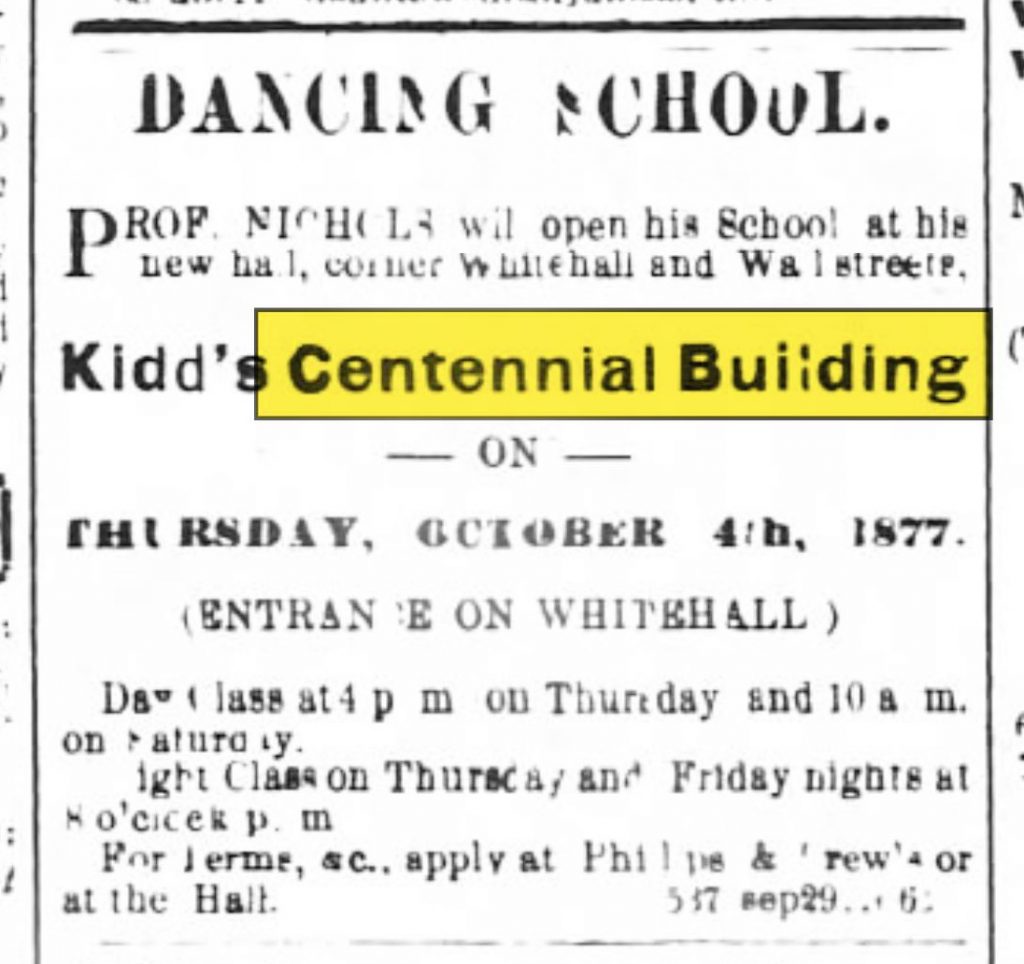

By 1877 Dr. George W. Marvin had professional offices in the Centennial Building “where patients could get reliable treatment for all diseases.” Also, in September Professor Nichols had a dancing school in the building evidenced by this advertisement from The Atlanta Constitution for September 30, 1877. In the late 1890s another dancing school would take over the space headed by W.J. Faulkner.

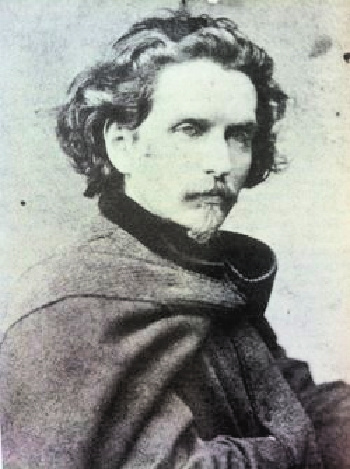

In 1878, the artist Albert Capers Guerry (1840-1898) had some of his paintings on exhibit at the Centennial Building. Guerry traveled up and down the east coast to make his living and had painted several Georgia notables. Guerry would go on to paint three U.S. Presidents – Harrison, Cleveland, and McKinley. All three portraits are part of the White House art collection today. Guerry lived in Atlanta from 1892 until his death and is buried in Washington, Georgia where his daughter lived. In 1893 his studio was located on the top floor of the Equitable Building.

Just prior to Captain Kidd’s death in 1881, a four-story brick building was added to the Centennial lot with “a wide and spacious area separating it from the Centennial Building.” The new building had a “large brick smoke stack, making it suitable for light manufacturing purposes.”

Since both buildings were in what was then the central business section of the city, Captain Kidd could ask for and receive the highest rents in the city. In fact, the Centennial Building earned $10,000 per year in rental fees for Captain Kidd, and it was estimated that the new four-story building would have earned him an additional $2,400 per year in rent.

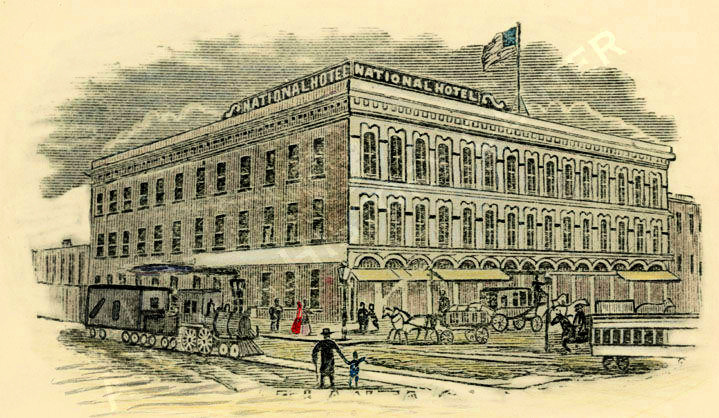

Captain Kidd was well known across the city of Atlanta and was seen on the streets right up to the day he died because of a paralytic stroke. His remains were removed from the rooms where he lived in the National Hotel to the home of his good friend and business partner, John Henry Mecaslin, where Kidd’s funeral would be held.

The National Hotel sat on Peachtree Street (later this location was home to the Peachtree Arcade and today’s former First National Bank building sits at 2 Peachtree Street).

At the time of his death Kidd’s fortune was said to be around $253,000 and the number increased once various properties, stocks, and bonds were sold at public auction. The entire Centennial lot was sold after Kidd’s death at auction on March 7, 1882. The sale, conducted by George Washington Adair (1823-1899), was described as “probably the most important sale of real estate which Atlanta had ever had.” It is interesting to note that even Adair was once a tenant of Captain Kidd renting space in the Centennial Building for his offices when the Kimball House burned in 1883 until 1885 when he moved to the second Kimball House. In addition to the Centennial lot another lot on Marietta Street was sold as well as a lot on Merritt’s Avenue and a long list of stocks and bonds.

Those who enjoyed a huge windfall from the proceeds of the sale and the distribution of other property included Kidd’s sister Jane (Kidd) Clark who still resided in Ireland. She easily saw at least $100,000. Mary A. Miller, the sister living in Philadelphia received a three-eighths portion, and the nephew, Hugh T. Pigott received a one-eighth portion. At the time of Pigott’s death in 1895 it was said the fortune received was “considerable” so a one-eighth portion was still quite sizable. Another cousin would receive $1,000. The Captain’s namesake, William Domineck Lagomarsino (1873-1943), son of John Lagomarsino, a candy and confection dealer, would receive one share of stock in the Atlanta National Bank. Another namesake, William Lynch, son of Michael Lynch also received a share of stock in the bank.

John Henry Mecaslin received $10,000 and all of Kidd’s interest in the properties they owned jointly which included one lot on Decatur Street, one lot in the town of West End (yes, it was once a town) that was located at the corner of Lee and Gordon, and one tract of land lying partly in the county of Macon and partly in the county of Lee in the state of Alabama.

The bidding for the sale was expected to be lively, but it was also a fact that no one at that time would have the funds to purchase the Centennial lot alone. It would be necessary for individuals to join up in a syndicate or partnership to fund the purchase.

The day after the auction a reporter asked G.W. Adair if the sale of the Kidd property was the largest undertaking of Adair’s auction business. Adair answered, “No, the heaviest sale I ever made was the sale of the Mitchell heir ‘s property – the old park – where the Kisers are now. It brought $250,000, and I made $7,500 in commissions in the one day.” When the reporter inquired about Adair’s commissions on the Kidd property, Adair promptly said, “That’s nobody’s business.”

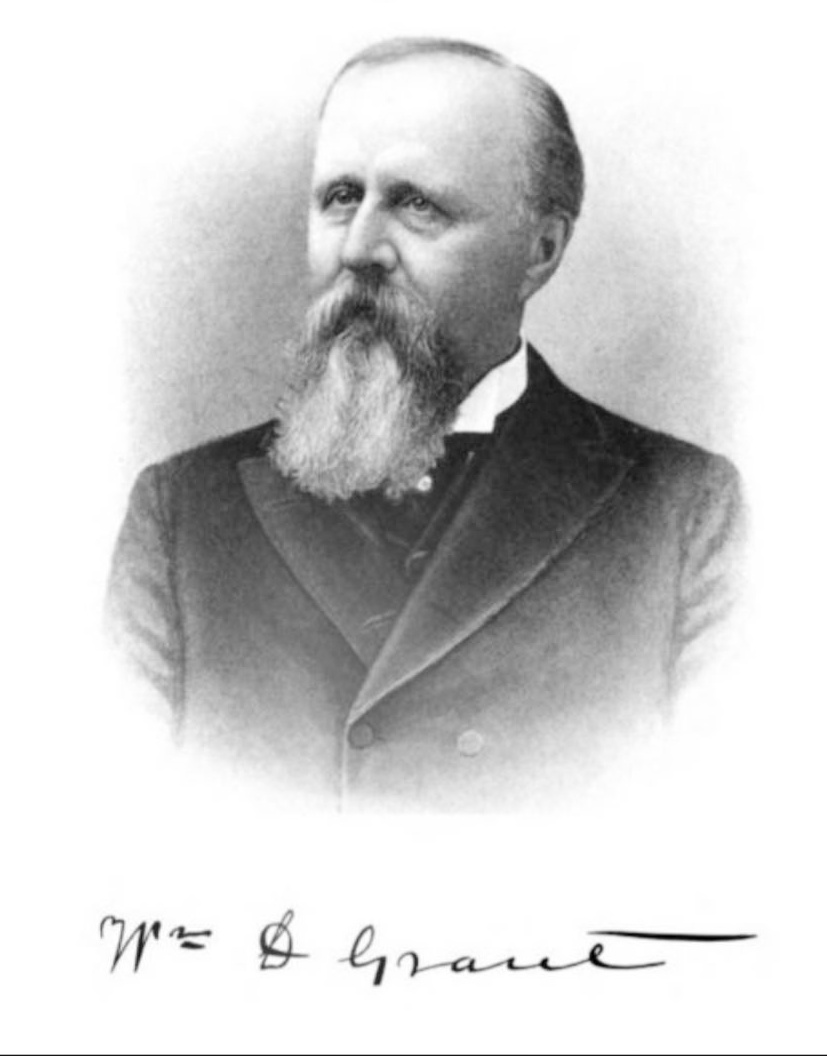

John Thomas Grant (1813-1887) and his son, William Daniel Grant (1837-1901) ended up with the highest bid for the Centennial lot, $112,000, and once the papers were signed, they immediately placed the newer four-story building for rent. John Thomas Grant was a railroad executive partnering with Lemuel Grant (namesake for Grant Park) constructing railroads not only in Georgia but all across the South. William Daniel Grant was known for supervising the fortifications around Atlanta during the Civil War and along with his father was a real estate investor. He built the Grant Building (Prudential Building) which still stands at 44 Broad Street in 1898. It is among the oldest steel structures in Atlanta and is the second oldest in the southeastern United States.

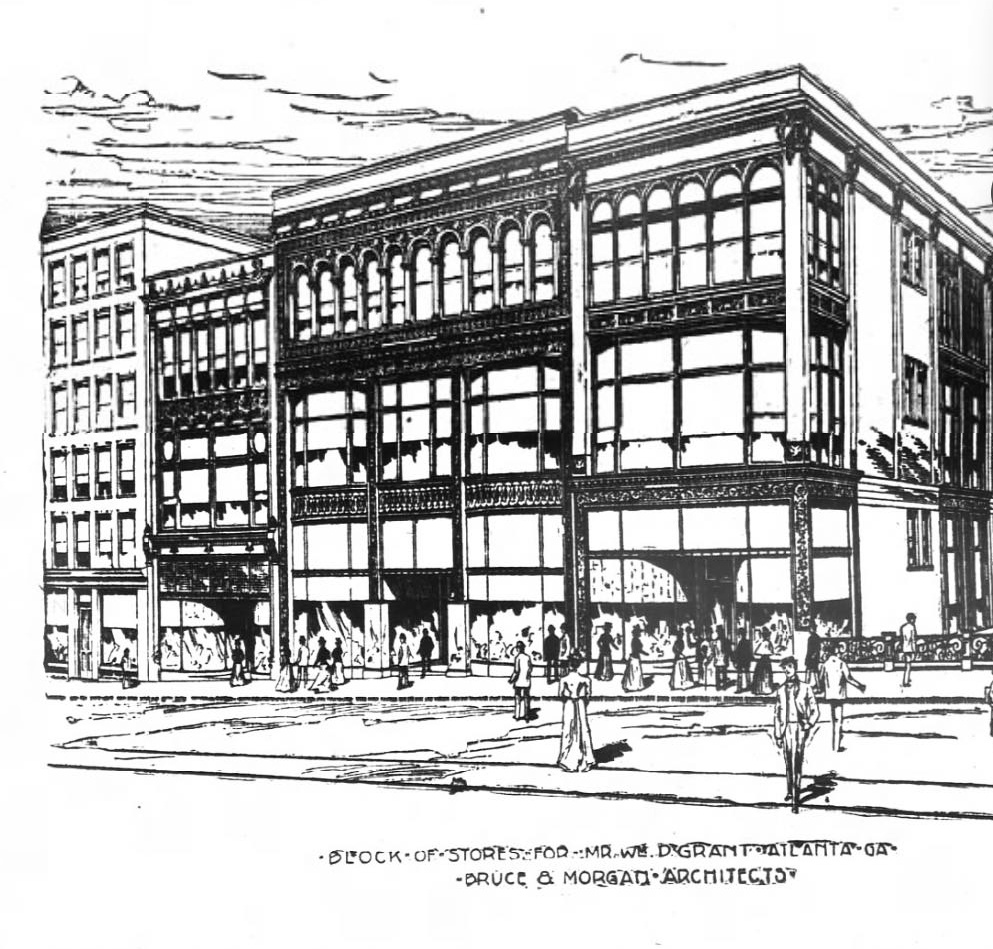

By the middle of July 1901, it was reported viaduct construction was well underway close to the Centennial Building and it had “begun taking on a bridge-like appearance.” The Century Building was also in the process of demolition to make way for a new building W.D. Grant was building which would be referred to the W.D. Grant Block that would contain three storefronts described as “the viaduct corner fronting the railroad” and the “corner of Whitehall Street and the railroad, westside.” The four-story building on the Centennial lot was not demolished in 1902 and longtime tenant, Byrd Printing Company, remained there for a bit longer.

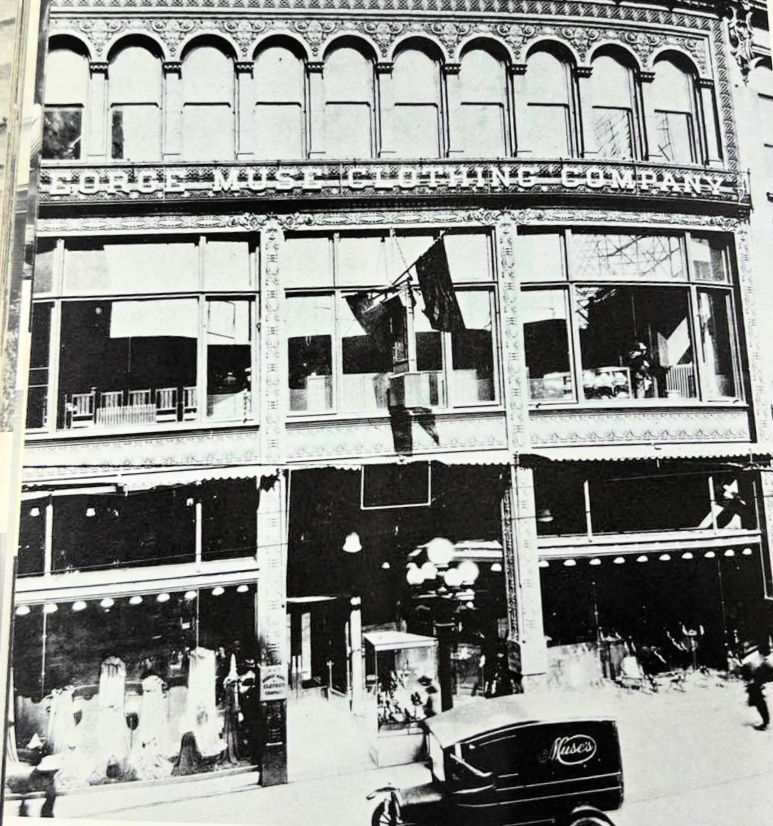

Grant employed Bruce & Morgan as the architects and C. Everett Clark Company was the contractor to construct the new building. Work was to be completed by March 1902. The drawing I have placed below was published in The Atlanta Constitution to show how the building would look. The center space would be taken by the George Muse Clothing Company, Eiseman & Weil would rent the corner store that had a sixty feet front and was thirty-five feet wide, and S.H. Kress & Co. took the spot nearest Alabama Street.

Different colored pressed brick was used for each separate storefront. Terracotta, ornamental iron, and steel were also used. There would be three stories with one story below the entrance and viaduct on the railroad front. The building also used a large quantity of plate glass mainly for light. Two large skylights, twenty-five feet in diameter, were used near the center of the stores. Underneath each skylight was a dome of ornamental art glass which was placed there to relieve the glare and to give an attractive finish to the ceiling.

Here is a 1917 photo of the Muse’s location in the new building. Muse’s would move on to another location in 1921.

So, there you have it. The long and winding history of the Centennial Building in Atlanta. It was once a landmark, something Atlantans pointed to with pride. It was connected to many of the early pioneer businessmen who were important to Atlanta’s history.

Today, the Centennial Building is just another addition to a long list of lost landmarks for Atlanta.

Leave a Reply