Yellow fever has hit Brunswick.

Those five words were reported in The Atlanta Constitution on August 13, 1893 and struck fear into the hearts of every person that read them.

Even though Carlos Finlay, a Cuban physician, identified yellow fever was carried by mosquitos as early as 1881, his research would not be taken seriously for two more decades. In 1893, yellow fever was a mystery and the mere mention of it could cause a city-wide panic. The disease would sweep in, wreak havoc, and disappear just as fast. There was no consistency, no explanation, and it was a nasty way to die.

Initially, yellow fever symptoms are very similar to other ailments – fever, chills, loss of appetite, back pain and headaches – that would come and then dissipate. In approximately fifteen percent of the people who develop initial symptoms the disease transitions into severe abdominal pain, liver damage which causes the skin to yellow, internal bleeding, and bloody vomit that was termed “black vomit.”

The fear experienced by Atlanta’s citizens reading those words was nothing compared to what was going on in Brunswick. The yellow fever outbreak began with one or two reported cases. City officials tried to keep the news quiet, but once they were forced to issue statements and confirm the city had yellow fever cases the citizenry was in a panic.

One of the first reported cases was John W. Branham who happened to be the assistant surgeon of the Marine Hospital service of the United States. A quarantine zone was set up outside Branham’s home. Once Brunswick’s mayor, Thomas W. Lamb, acknowledged Branham’s illness many citizens began to send their trunks to the depots. Within a short time, the Brunswick and Western Railroad depot checked in 98 trunks for the first departing train. Eventually, five extra coaches were added to accommodate those departing. Business owners and other local leaders hurriedly published desperately optimistic reports of the outbreak being an exaggeration, but that all quickly fell apart.

By August 21, 1893 real panic had set in. The East Tennessee Railroad fixed a lower rate of one cent for the poor who wanted to escape to Chattanooga, and ten coaches were made ready for the crush of people. When the coaches backed up to the depot the sleeping car struck a pile of trunks, knocking down two ladies in the process. The impatient crowd surged to the doors and windows which were locked. It was reported that some women climbed over trunks and men’s shoulders in order to make sure they were first in line to board the train.

Soon, two more cases of yellow fever were made known to the public. Peter (S.H.) Harris was the second victim. Government officials assumed control at that point and ordered that he be moved to the Branham home inside the quarantine zone. Harris fought the authorities during the move, and it was reported that as he was carried into the Branham home, he gave one horror-stricken glance about before fainting. He never regained consciousness, and although not in an alarming condition prior to his move, he rapidly sank and by August 24th was dead.

A third case involved a young child. As soon as the parent was told his child had yellow fever, he scooped the child up and ran for the woods.

Eventually a posse located the man and his child in a cabin deep in the woods. In this case it was decided to leave them where they were because public sentiment supported the father. Guards and medical professionals were assigned to stay with them.

By this time the vicinity that had become known as the “fever district” – an area bounded by Stonewall, George, Dartmouth, and Newcastle Streets – was as silent as a tomb. Only 3,500 people remained from a normal population of 12,000.

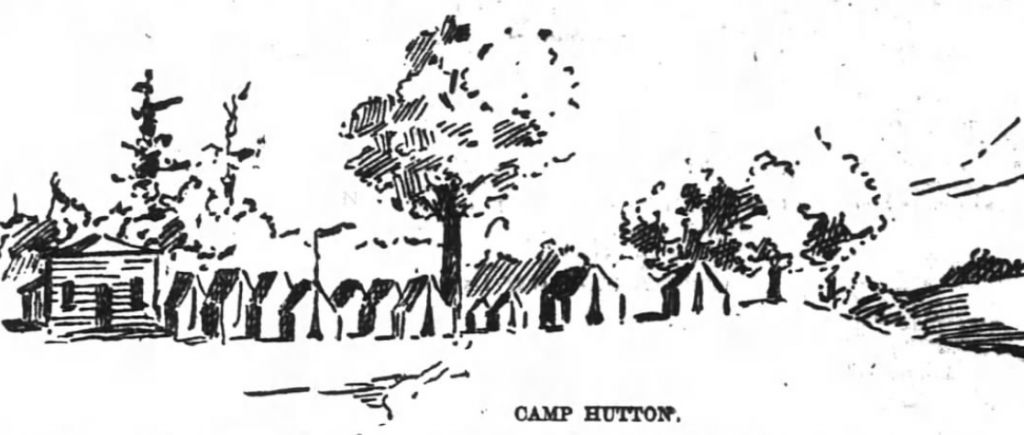

As the days wore on leaving the area grew more difficult. In fact, only the early evacuees were successful. A quarantine at Savannah kept people from going there, but the route by way of Albany and Macon was open. Still not everyone got out, so many found themselves detained by the Army at Camp Hutton at Waynesville, 23 miles west of Brunswick. Martial law prevailed.

Yellow fever and the prevailing hysteria weren’t the only thing plaguing Brunswick during this time. On August 27, 1893 the Sea Islands Hurricane made landfall at Tybee Island near Savannah. The storm moved up the coast killing an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 people mostly from storm surge that reportedly reached 30 feet in some places but only reached the 6 feet mark at Brunswick. In an online article regarding the yellow fever epidemic and hurricane by Leslie Faulkenberry it is noted that the reason why the hurricane failed to inflict a high number of casualties in Brunswick was because so many families had evacuated due to the epidemic. Most of deaths were on the barrier islands of Georgia and South Carolina dying during the storm. Countless others died to disease and starvation in the months that followed.

For those that had remained in the city the grocery stores had been closed and their stocks sent out of town. Even if those who stayed behind had money to buy food, there was none to be had. Many went for two days or more without any food at all.

Think about it…yellow fever all around and absolutely no food or other any type of services. Things broke down rather quickly and the frantic atmosphere would have quickly escalated to violence had relief not arrived.

I located all sorts of efforts from around the region to collect aid to send to Brunswick and the surrounding area in the days that followed the epidemic, hurricane, and flooding. Click through to part 2 where I detail one such effort in Atlanta.

If you enjoyed this true history tale you will like my latest book – Georgia on My Mind: True Tales from Around the State which contains 30 true tales from all around the state including three stories from Atlanta, and yes, there will be volume two out soon! You can purchase the book here…in print and Kindle versions.

Leave a Reply