This web article began with a simple vintage postcard featuring an old motel I recognized from my childhood along Stewart Avenue now known as Metropolitan Parkway – the Colonial Motor Lodge. I was researching the motel to verify the owner’s name for a very short Facebook post in the group I administrate – You’ve lived in ATL a long time if you remember…, and instead of a simple business history, I ran across an Atlanta family who not only sacrificed one son to World War II but two sons, and I wanted to document the story here.

The Carby family had lived in Minnesota and Louisiana before moving to Georgia around 1935. Henry “Hank” Clayton Carby (1894-1978) was a manufacturer’s representative for Smith Welding Equipment Company out of Minneapolis, and he and his wife, Hannah B. (Votendahl) Carby (1897-1978) settled their family in the Morningside section of Atlanta in a lovely home at 1321 Lanier Boulevard, N.E. that still stands today. You can click through to see a video of the home.

The Carby’s oldest son Henry “Clayton” Carby, Jr. (1919-1944) had begun college at Louisiana State University prior to the family’s move but soon transferred to Emory University. Middle child, Eugene Manning Carby (1922-1943), enrolled at Atlanta’s Tech High School, and baby daughter, Gayelle “Gail” Carby (1924-2003), attended Girls’ High which at that time was located on Rosalia Street. The school later became Roosevelt High School and today operates as Roosevelt Lofts.

During those first few years living in Atlanta the newspapers were full of stories regarding how Hitler was sweeping across the European continent, yet the war seemed far away, and the future appeared bright for the Carby family. Moves can be challenging for a family, but the Carby children seemed to thrive fitting into Atlanta life easily. Eugene graduated from Tech High in June 1940 and enrolled at Georgia Tech, while Gail’s name often appeared in Atlanta newspapers as an officer for the Beta Epsilon Mu sorority at Girls’ High.

Then that pivotal day came – December 7, 1941 – when the United States was attacked by Japanese forces at Pearl Harbor Hawaii. So many across the entire world had the direction of their lives changed on that day including the Carby family.

By December 1941 Eugene Carby was a cadet at the naval station on the old Camp Gordon site in Chamblee, and by January 1942 he had entered the Army Air Corps.

One month later Eugene was at Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Alabama at the Air Corps Replacement Center. There he received basic military and ground school instruction and preliminary flight training. In August 1942, Eugene was one of six Georgians who received commissions as second lieutenants in the Army Air Corps and received his navigator wings at Turner Field in Albany. By February 1943, he was stationed at MacDill Field in Tampa before heading overseas in May 1943 where he ended up as a navigator on a B-26 Marauder Medium Bomber, a member of the 449th Bomber Squadron, 322nd Bomber Group, 9th Air Force. While the photo I’m sharing below is not Eugene’s plane, it is like the one where he served as navigator.

Sadly, Eugene was killed on June 4, 1943, when his plane crashed three miles southeast of RAF Pembrey, an airfield used by the military during World War II located in Pembrey, Carmarthenshire, Wales on the coast. The site is now a public airport. A memorial service was held for Eugene who was only 21 years old on June 20, 1943, at Morningside Presbyterian Church where the Carby family were members. Eugene has a page at the American Air Museum here. He most certainly lived up to the motto of the 322nd Bomb Group – Recto Faciendo Neminem Timeo or I fear none in doing right.

Tragically, the Carby sacrifice wasn’t over.

The Carby’s oldest son, Henry “Clayton” Carby, Jr. was attending Emory University when the United States entered World War II.

By January 1942, Clayton one of eight Georgians appointed as aviation cadets in the United States Naval Reserve. At the end of May 1942, he was transferred to the U.S. Naval Air Station at Miami, Florida for advanced flight training having just completed his primary and basic flight training at Jacksonville. Advanced flight training was completed by mid-July 1942 and Clayton Carby was now Ensign Carby. By February 1943, he was stationed as a Navy pilot aboard an aircraft carrier with the Atlantic fleet and was at Norfolk, Virginia when he received word of his brother’s death in June 1943. Based on a citation for an award Clayton received posthumously I was able to determine he was assigned to the USS Bunker Hill (CV-17).

On January 18, 1944, Clayton Carby’s parents received a telegram that their only surviving son’s torpedo bomber and its entire crew had been reported missing somewhere in the Pacific by the U.S. Navy as their aircraft had pounded the enemy at Kavineng, New Ireland on Christmas Day 1943.

Kavineng is the capital of the Papua New Guinean province of New Ireland located at Belgai Bay. The island had been taken by the Japanese almost a year prior and most of its European citizens were killed over time. The war destroyed the island, and today, planes and shipwrecks litter the harbor at Kavineng as a reminder of that horrible history.

The last letter the Carby family had received was dated December 17, 1944, and Clayton mentioned he had been recommended for the Purple Heart and two Air Medals. The medals were probably due to his actions during the Battle of Arawe that had begun on December 14, 1943.

There was no word about Clayton’s whereabouts for several days until February 10, 1944, when Clayton and his gunner, C.A. Morken, were found on a tiny pin-point island in the Pacific Ocean. They had crash-landed into the sea. The radio operator, R.C. Reynolds, died. Carby and Morken, floated in a tiny rubber boat for 27 days until they reached a tiny spit of sand where they had remained for another 14 days.

The pair were spotted by a patrol bomber and taken aboard a seaplane tender around February 3, 1944, but this rescue proved to be ill-fated as well. In a tragic twist of fate while the Carby family was rejoicing in Atlanta, the pair were again missing as passengers on a rescue plane from the point where they were picked up. I cannot even imagine the joy of being rescued after an ordeal like the one Carby and Morken suffered only to experience another crash landing during their rescue.

By April 1944, the men were presumed dead and were listed as lost at sea.

Emory University included Clayton’s name during their tribute to the Emory students who died in service in World War II in early June 1946, and it was announced in November 1944 Lt. Henry C. “Clayton” Carby would receive another medal – the Soldier’s Medal – an award given by distinguishing oneself by heroism not involving actual conflict with the enemy.

In a ceremony in November 1947, Clayton’s medal was presented posthumously by Captain E.T. Neale, the commanding officer at the Atlanta Naval Air Station to his mother. The citation stated, “For meritorious achievement in aerial flight as pilot of a Torpedo Bomber in Torpedo Squadron Seventeen, attached to the USS Bunker Hill, in action against enemy Japanese forces in the vicinity of Rabaul, New Britain, on November 11, 1943. Although wounded during a determined fighter attack in which his plane was riddled by 207 bullet holes, Lt. Carby boldly executed a close-range torpedo run over a heavy combatant ship despite intense antiaircraft fire from ship and shore batteries and thereby contributed to the success of the mission in this area. By his skilled airmanship, courage and devotion to duty, Lt. Carby upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

There were no remains found for Clayton, and I am not certain Eugene’s body was returned to the states, but in July 1948, the three remaining Carby family members held a funeral service for their heroic sons at Westview Abbey, and it was stated the entombment would also be in the Abbey where you can find them listed among the Find-A-Grave entries here and here.

The Carby’s only surviving child, Gail, had graduated from Girls’ High and was attending Oglethorpe University in 1943. She would go on to the University of Georgia where she was assistant news editor for the Red and Black in 1945. By 1959, when she became engaged to L.C. Lanier, she was working for WRC Publishing in Atlanta.

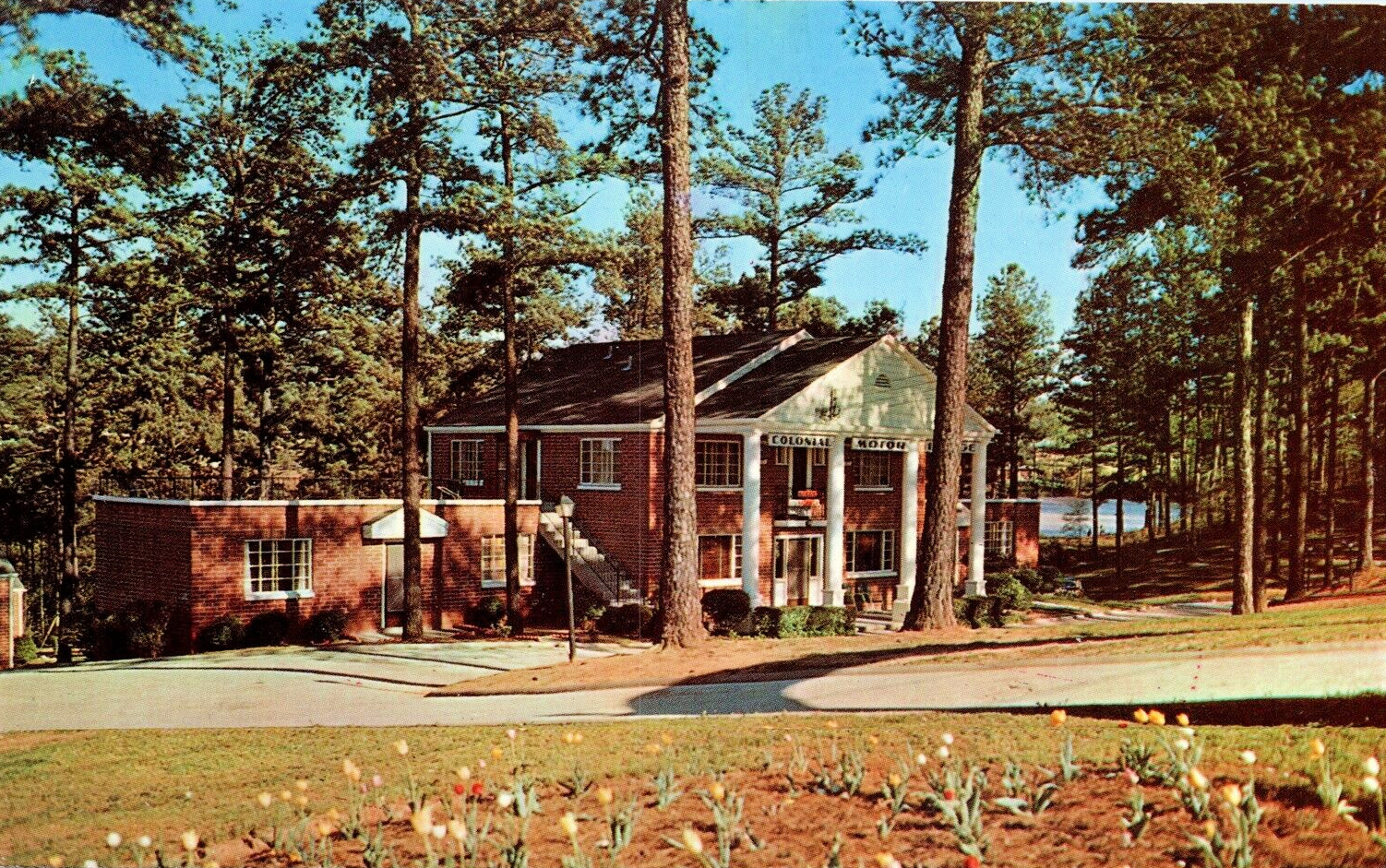

Hank Carby eventually retired from Smith Welding Equipment Company, and in his retirement went into the motel business. In 1949, he and Hannah built the Colonial Motor Lodge at 2720 Stewart Avenue. The motel at that time consisted of three buildings in a pine grove – a main building where Hank and Hannah lived along with eight rooms and two additional buildings with six rooms each.

The ad I’ve placed above indicated the rooms were paneled in fir and the lobby area in African mahogany with oak floors and Venetian blinds throughout. For a time, the motel was profitable, but the Carby’s moved on in the late 1970s noting in a “for sale’ advertisement the motel grossed $122,000 annually.

The Colonial Motor Lodge was sold to Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Bardenwerper, and Hank and Hannah Carby lived out the remainder of their lives in Pinellas, Florida where Hank enjoyed golf and dabbling in real estate. They both passed in 1978 a few months apart and are buried at Westview Cemetery in Atlanta close to their sons who forever remained in their early twenties and became members of our greatest generation and American heroes.

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my latest book – Georgia on My Mind: True Tales from Around the State – which contains 30 true tales from all around the state including three stories from Atlanta, and yes, volume two will be out soon! You can purchase the book here…in print and Kindle versions.

Leave a Reply