It was a windy Kansas morning when Carry Nation, black veil flapping like a war flag, packed up a buggy full of rocks and rode into history.

Six feet tall and fueled by faith, fury, and a whole lot of Old Testament-style smiting, Carry Nation wasn’t just another woman with a cause—she was a one-woman wrecking crew, literally. Long before Rosie the Riveter flexed her bicep or Suffragettes marched on Washington, Carry Nation was hurling whiskey bottles and busting beer barrels to fight what she saw as the root of all evil: liquor.

Carry’s crusade began in heartbreak. Her first husband, a doctor, died young and ravaged by alcoholism. That loss lit a fire in Carry that would never be extinguished.

After marrying her second husband, David Nation, the couple moved to Kansas, a dry state in theory, if not in practice. To Carry’s horror, the saloons still flourished—often with the blessing of local authorities who looked the other way.

She was appalled. And she wasn’t quiet about it.

She harangued drinkers in the streets, confronted saloon owners during church services, and knelt in prayer outside bars, demanding God smite the whiskey slingers. Kansas sheriffs shrugged. The barkeeps laughed. Until one day, Carry Nation stopped preaching and started smashing.

That morning in Kiowa changed everything. Carry walked into a saloon and let fly—first with rocks, then with whatever she could grab. Billiard balls. Beer bottles. Even a hat rack. She demolished three saloons before the law arrived, and even then, no one dared stop her. The bars were technically illegal, after all.

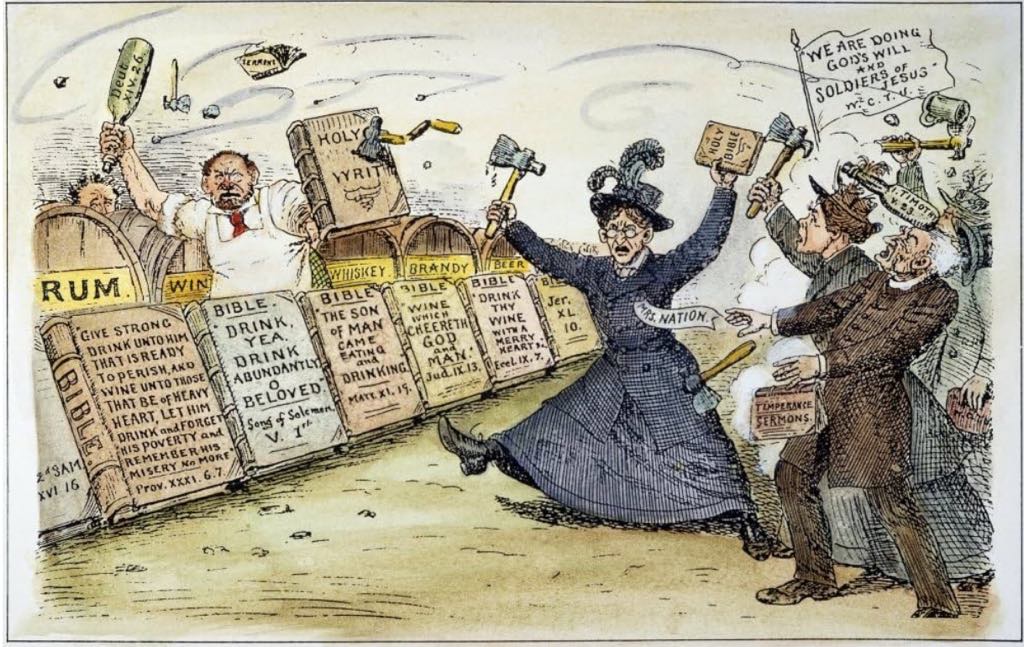

Soon she traded in her rocks for a hatchet. “Hatchetation,” she called it—her signature campaign of saloon demolition, righteousness in one hand and iron in the other. Her notoriety exploded. She was arrested. Fined. Beaten. But also funded, bailed out, and cheered on by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and ministers who saw her as a fearless instrument of divine justice.

She told women across the country: “If you don’t have a hatchet, a fireplace poker will do.”

Carry Nation became a symbol of the Prohibition movement—and a media sensation. Crowds gathered to hear her thunder against “men soaked in nicotine, beer-besmirched, whiskey-greased, red-eyed devils!” She sold souvenir hatchets.

She gave speeches across the nation. And though she couldn’t vote, she wielded a different kind of power: outrage, spectacle, and stubborn, unwavering purpose.

“If you don’t do it,” she warned the lawmakers, “then the women of this state will do it. You refused me the vote, and I had to use a rock.”

She was right. The pressure mounted for years. By 1919, the Volstead Act was passed, ushering in Prohibition nationwide. While Carry Nation didn’t live to see it—she died in 1911—her legacy was already cemented, not just in broken bar mirrors and beer-slicked saloon floors, but in American cultural memory.

History hasn’t always known what to do with Carry Nation. She was a hero to some, a nuisance to others, and a symbol of moral reform to the growing chorus of women who had long been shut out of political power. Whether you see her as a holy avenger or a well-intentioned fanatic, one thing is clear:

Carry Nation didn’t wait for permission. She didn’t sit quietly in the pews. And when the law failed, she picked up a hatchet and said, “God is standing by me.”

Leave a Reply