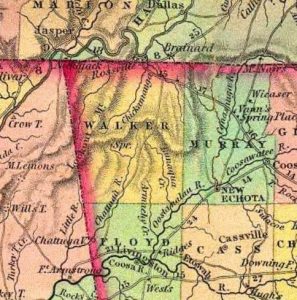

Walker County, located in the extreme northwest corner of Georgia, was created on December 18, 1833 using land that had been part of the Cherokee Nation. By the end of its first year of existence Walker County had chalked up its first legal hanging.

In 1834, Walker County was much larger than it is today covering what is today not only Walker County but Dade, Catoosa, a part of Whitfield and a part of Chattooga counties. White settlers were slow to enter the area mainly due the mountain ranges trending eastward and westward make it inaccessible from the Tennessee settlements on the north and the settlements in Georgia on the south. The pioneers had to follow circuitous routes through the narrow valleys, and it was for many years very sparsely settled.

One morning, in 1834, an Indian woman appeared and stated two men had been murdered at a cabin in an adjacent valley. The alarm spread, and a small posse of white men repaired to the lonely cabin, where they found the bodies of the men who had been brutally slain with an ax.

John Hog Smith, who had a trace of white blood in his veins and was known to be a rather desperate sort with a bad reputation, was the only person living in the vicinity, and he was placed under arrest, as the Indian woman had already accused him of committing the crime. When arrested blood was found on his person and on the key of the door with which he unlocked his cabin.

The book, “The History of Walker County” by James Alfred Sartain (1932) differs from many newspaper accounts that state the murder scene was John Hog Smith’s cabin, and that he and another Cherokee murdered the white men when they were found asleep in the doorway of the cabin.

Either way, two men were murdered, and at least one Indian was accused of the murder.

The sheriff of Walker county was concerned thinking settlers might resort to mob violence and didn’t feel he had the sort of secure jail that was needed, so the Sheriff took the prisoner to Lawrenceville in Gwinnett County, a trip that was one hundred and fifty miles away due to the winding mountainous roads. Later, Smith was moved again to Cassville, the county seat for the now defunct Cass County (today’s Bartow county) for trial. The testimony was overwhelming, and Smith was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged.

An effort was made to move legislation through the Georgia legislature to pardon John Hogg Smith, but the bill failed in a Senate vote at the end of November 1834.

Naturally, many of the Cherokee Indians were terribly stirred up over the sentence, and many expressed a desire to rescue him. They argued the white settlers were determined to make an example of Smith to overawe the lawless element across the broad area of Walker county.

The Indian woman who first reported the crime to authorities let the Walker County sheriff know a party of Cherokee warriors were planning to rescue Smith, so a counterplan was quickly devised.

The sheriff mounted his horse and secretly rode away before dawn on the Tuesday morning before the execution on Friday. At the same time a runner was sent to advise the white settlers on the Tennessee River of the threatened trouble.

The brave sheriff rode night and day, up and down steep mountainsides and hills, till he reached Cassville just as the officials were getting ready to depart with their prisoner for the scene of the hanging.

The mountains were full of Indians, and what were far worse, renegade white men, many of them members of the famous “Pony Club,” the most daring desperadoes that ever terrorized the law-abiding people of four great states – Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida.

The lawmen took every precaution to prevent a surprise and rescue, for well they knew that such a formidable force could be raised as to completely overpower them in some of those narrow passes of the mountains unless they kept well on their guard.

The presence of such a show of force alone prevented a bloody outbreak, and through the silence of the wild mountain passes and the uncultivated valleys they made their way with never a solitary Indian in sight.

At last, on Friday morning, they reached the spot designated for the execution at Crawfish Springs, a place important to the Cherokee and named for Chief Crawfish. Natives also had called the place “Spring of Dead-Man’s Land” became so many Cherokees had died at the location due to typhoid fever at one time.

A crude gallows had been erected in the grove near the spring. The troops drew up in a hollow square about the gallows with a crowd of eager spectators that had come from every direction to witness the first hanging that had ever occurred in that county.

The old citizen from whom the facts of this story were gleaned was a boy at the time and was present on that momentous occasion. The appearance of the culprit made a deep impression on his mind. Smith was a splendid specimen of physical manhood – tall and brawny, but with a forbidding, murderous face, which gleamed with a terrible expression of mingled fear and anger as he mounted the scaffold. He had evidently been informed that an effort would be made to rescue him and preserved a defiant demeanor and maintained a sullen silence to the last.

The sheriff read the death warrant, an aged minister prayed for the doomed man and delivered a short exhortation. The prisoner, just as the black cap was adjusted, cast a despairing glance over the multitude of merciless faces; the trap was sprung, and the savage murderer was launched into eternity.

A grave had been dug near the foot of the gallows and as no one appeared to claim the body, it was buried there in the lonely forest, near the spring, and there remains in its solitary resting place without any sign to mark the exact spot.

In later years the village of Chickamauga sprung up near the famous spring and eventually became one of the most picturesque and popular summer resorts in north Georgia as well as the site of a notable Civil War battle, but there are very few who are aware of the fact that the first victim of justice in the newly formed Walker County met his punishment there and that his body rests beneath the shelter of those old trees whose shade adds so much to the attractiveness of that romantic resting place.

If you enjoyed this true history tale you will like my latest book – Georgia on My Mind: True Tales from Around the State which contains 30 true tales from all around the state including three stories from Atlanta, and yes, there will be volume two out soon! You can purchase the book here…in print and Kindle versions.

Leave a Reply