The basics are this – the state of Georgia purchased several hundred guns in 1859, paid half the purchase price, and then issued bonds to cover the balance which would mature in 20 years. The matter of the bonds came before the Georgia state legislature regarding payment in 1869, 1893, 1904, and 1906, and as far as I can tell, the bonds were never been paid.

To understand the matter we have to go all the way back to November, 1859 when the Georgia legislature directed Governor Joseph M. Brown to buy sufficient arms to equip all of the militia companies of the state that then existed and might be formed in 1860 by appropriating $75,000 for the purpose. On November 14, 1860 Governor Brown contracted with the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company of Hartford, Connecticut to supply the state with 1600 rifles for a stipulated price.

By the end of the month the guns were delivered to state authorities at Milledgeville, and the state of Georgia paid the arms company a cash payment of one-half the purchase price – $25,000 – with the authority of the legislature.

Governor Brown then issued bonds for the unpaid half. However, there was a delay in engraving the bonds, and they did not reach the Governor until February 1, 1861. The bonds were made payable to the bearer at six percent interest and due twenty years from the date making the maturity date February 1, 1881.

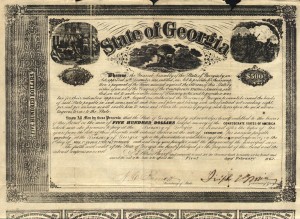

The bond I’ve posted below is not one of the bonds for the rifles, but it is similar to how the Mattingly bonds would have looked.

In 1868, George Mattingly of Washington, D.C. purchased twenty-two of the bonds. There were others described as northern capitalists who also purchased the bonds, but Mattingly seems to be most aggressive regarding payment demands.

The matter of payment was first brought up in the legislature in 1869 where the judiciary committee seemed agreeable regarding payment, but a house vote was never taken.

In 1893, the legislature was again pressed for payment when the bond holders asked permission to have the matter adjudicated in the courts. This was denied. The Georgia legislature would be the only tribunal to settle the matter.

In 1904, the claim was again pressed, but no action was taken. The matter came up again in July, 1905 with a special committee. By this time Mr. Mattingly had passed away and his heirs were pressing for payment. The committee of eleven – one representation from each congressional district, made a favorable report and introduced a bill making an appropriation of $24,200 for the payment of principal and interest, but a vote was never taken.

In August, 1906, B.H. Hill, of Dooly County introduced the Mattingly Bond Bill asking for payment once again. Representative Hill’s brother, Charles D. Hill who was Solicitor General for the Fulton County courts also lobbied for the bill as the brothers represented the Mattingly heirs.

The discussion of the Mattingly Bond Bill occupied almost the entire time of the session. The justice of the claim was supported by some and questioned by others. The debate on the measure was long and impassioned, and the house seemed almost equally divided. During the roll call nearly every member took advantage of the opportunity to explain his vote in a three minute address which in some cases became an impassioned argument.

It seemed rather cut and dry. Guns were purchased and funded through bonds. The bonds had matured and should be paid.

So, what was the problem?

Some of the legislators stated everyone should pay their debts – individuals, church, or state.

Mr. Milliken of Wayne County said he might have had one of these guns at Sharpsburg, but he was willing to pay his pro rata share of them. One of the legislators read a letter that had been written at some point by General Robert Toombs to a man in Connecticut stating it was a just debt. The point being made that if a staunch Confederate like Toombs who never regained his American citizenship following “the war” could agree to pay anything to a Yankee, then there was no reason why the legislature should as well.

Mr. Kelly of Glascock County opposed the payment because the north had taken the guns during the “late war”.

The discussion even caused a fight on the house floor the next day between Dr. T.R. Whitley of Douglas County, a member of the house and Solicitor General Hill of Fulton County. During Dr. Whitley’s remarks he voiced his opposition to paying the bonds, but mainly he made reference to the men who were alleged to be lobbying for the Mattingly bill – the Hill brothers. Mr. Hill accused Dr. Whitley of being against the bill because he had received no money to vote in favor of it. Dr. Whitley and C.H. Hill had a bad history going back a couple of years when they had found themselves on opposite sides of a slander lawsuit involving Judge Janes of the Tallapoosa circuit. Dr. Whitley accused Mr. Hill of using perjured testimony.

I’ve included a full recounting of the fight in my history column that appears in the Douglas County Sentinel each week….to be published Sunday, December 4, 2016.

This date the bonds were issued – February 1, 1868 – is important because it was twelve days after ordinance of secession was passed in Georgia. The guns had been delivered to the state of Georgia, a part of the United States, but the bonds dealing with the remaining payment for the guns were enacted by the state of Georgia, a part of the Confederate States of America.

The real point of issue between the speakers turned on whether these rifles, purchased in 1861 from the Sharp Rifle Company, were purchased for the purpose of rebellion with a view to the secession, which followed shortly, or merely to arm the Georgia militia against domestic disorder similar to the John Brown raid which had taken place shortly before in 1859.

Mr. Covington delivered an address in opposition to paying the bonds which had great effect. He drew a picture of the period when the bonds were issued by Governor Brown under the advice of Robert Toombs and Benjamin Hill. He connected the dots regarding how southern states were arming themselves for a great conflict, and that war was in the air in 1859. There was no doubt that the arms were purchased for the purpose of rebellion, and that the payment of this money was prohibited by the U.S. Constitution.

Remember learning about the 14th Amendment in your high school history classes? Basically, students are taught the 13th Amendment freed the slaves, the 14th gave the freed slaves citizenship, and the 15th amendment provided them the vote, but there’s so much more to it. A section of the 14th Amendment prohibits payment of any debt incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States.

That fact seemed to make the case for the legislators.

Yes, the old state debt had appeared before the house for the fourth time, and each time the claim did not get reach the voting stage until 1906 when it was finally killed in the house.

The old state debt was finally repudiated by vote of 84 to 66, and as far as I can tell the bonds remain unpaid today – 135 years later – and a little section of the 14th Amendment is the reason why!

Leave a Reply