Harper’s Magazine is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. I often use back copies as historical research to help me because the magazine dates to June 1850 when it was first published in New York City by the Harper brothers I’ve pictured below. Today, Harper’s is recognized as the oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the United States. The company also founded the magazines Harper’s Weekly and Harper’s Bazaar, and grew to include HarperCollins, the book publisher.

Recently, I acquired a few original pages of an article written for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine from the December 1879 issue (Volume LX – No. 355) to add to my historical collection containing various items – postcards, images, magazine pages, etc. regarding Atlanta. I bought these pages because I loved the images, but once I began to read the article it was like stepping back in history and finding myself at Five Points in December 1879.

I found a newspaper article from The Atlanta Constitution from April 1879 advising that Evan Howell (1839-1905), editor-in-chief of the paper, had written to the Harper brothers “suggesting that an illustrated article, or a series of illustrated articles, embodying sketches of the picturesque scenery of north Georgia and facts pertaining to the vast natural resources thereof, would not only add largely to the interest of their magazine, but would be timely and much-needed advertisement of one of the most productive sections of the south.”

Apparently, the Harper brothers agreed with Howell and on April 12, 1879, Ernest Ingersoll, a writer with Harper’s, and Frank H. Taylor, “an artist of considerable reputation,” arrived in Atlanta. They would remain in the city a few days and eventually make it their base while exploring the possibility of various articles.

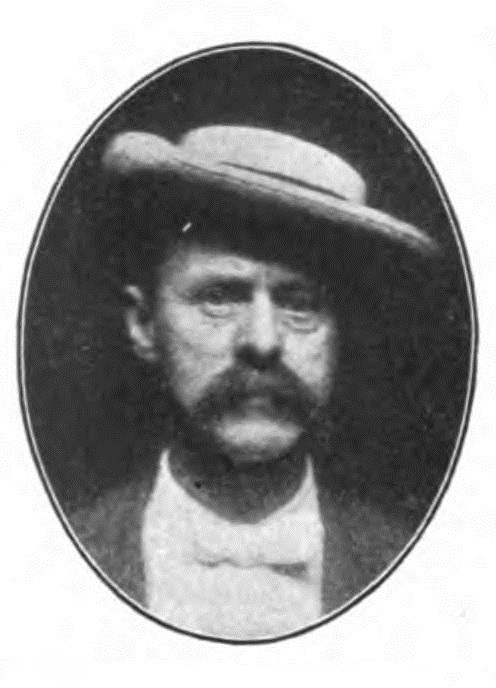

Ernest Ingersoll (1852-1946) was an American naturalist, writer, and explorer known mainly for his scientific and anthropology leaning articles including an investigation of the Mesa Verde Cliff dwellings with photographer William Henry Jackson in 1875. He also wrote articles for the antecedent of Field and Steam and from the 1890s to 1905, he updated guidebooks for Rand McNally.

Frank H. Taylor (1846-1927) opened his own lithography firm in Philadelphia in 1870 after completing a five-year internship with another firm. That same year Taylor also began serving as a “special artist” for various newspapers and publications including Harper’s. A “special artist” made sketches on-site that were later turned into wood engravings for printing. Special artists were used as photojournalists are today before the use of photography in newspapers became commonplace.

While I’m more interested in Taylor’s work in Atlanta and around Georgia, his most memorable assignment was in 1880 when he accompanied former president Ulysses S. Grant, General Philip H. Sheridan and their wives to Florida, Cuba, and Mexico. In retirement Taylor became known for his watercolors, washes and drawings of Philadelphia and other locations.

Too often I hear from the folks who read my books, from people who follow my social media pages, and members of my Facebook group – The Atlanta History Files, “If only I could go back in time and walk these streets…”

Well, here’s your chance to experience the streets of Atlanta in 1879 as Ingersoll and Taylor saw them. I’ve included here in italics the text of the article titled, The City of Atlanta along with Taylor’s sketches and additional information where I felt clarification might be necessary.

Enjoy your step back in time…

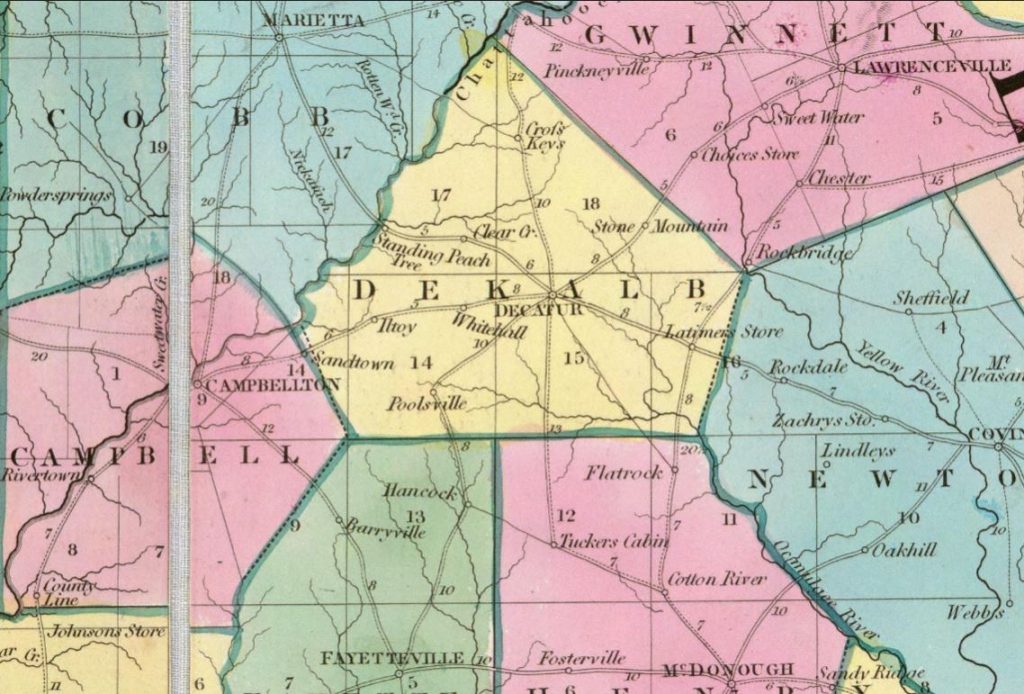

Atlanta, the present metropolis of Georgia, has had a history peculiar for a southern town. Those who have spoken of the city as the “Chicago of the South,” appear to have struck not very wide of the mark. Forty years ago, there was nothing at all here. Maps of the period, very minute and careful in their topography, show no such place.

Forty years prior to this article would be 1839. Below is a snippet from 1839 map of Georgia & Alabama produced by David H. Burr showing the vicinity where Atlanta would eventually show up but is too small in 1839 to register on a map.

All the wagon roads centered at Decatur, at Marietta, and Canton. Creeks and Cherokees occupied the whole region, and there was hardly even cross-roads at this point. The turnpike between Georgia and Tennessee did not pass through it, and no large river furnished facilities for navigation, or offered power to move machinery. How, then, did Atlanta come to exist at all; and much more, how did she succeed, like the goddess whose name she suggests, in outstripping all her older sisters, Augusta, Savannah, Macon, and the rest?

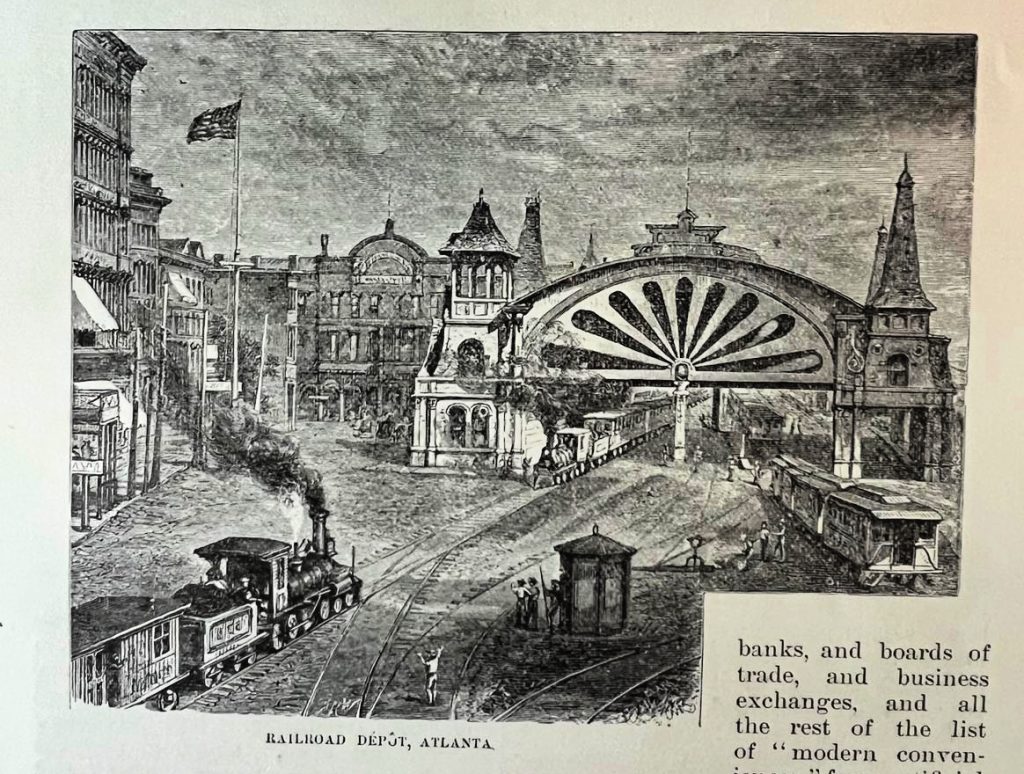

The answer is found in one word – railways.

Atlanta is a “flat” town and was put where she is by act of [the] legislature rather than by the natural course of events. It is an interesting and exceptional example of prosperity ensuing from forced conditions, and came about in this [way]:

When the experiment of steam locomotion had proved a success in England and was being introduced on this side of the Atlantic [Ocean], Georgians were quick to perceive that they needed this new invention, and as early as 1838 charters were granted to several interior railway companies. It was also seen that [Georgia] required railway communication with the West and Northwest, in the shape of a trunk line, in the advantages of which all the interior [railroads] could share.

The [state] legislature was there consulted, and in 1835 an act was approved authorizing the construction of a railway from the Tennessee line, near the Tennessee River, to the southwestern bank of the Chattahoochee River, “at a point most eligible for the running of branch roads thence to Athens, Madison, Milledgeville, Forsyth and Columbus.”

A survey was made accordingly, and it was found that at this point, seven miles east of the Chattahoochee, spurs of the Blue Ridge intersected in such a manner that a natural centre occurred for all the most likely routes of railway communication then surveyed or likely to be laid out. Here, then, right out in the woods, it was resolved to begin the “State” railway north to the Tennessee line, and the spot naturally came to be known as “Terminus.”

Passengers on the Air Line [rail] Road to Washington will remember a little breakfast station called Central, up in the mountains of Western South Carolina. As the train comes round the bend of the hill, and slows up, a dinner-bell is heard and the eye takes in a white building, with a long cool piazza, where stands a man whose genial smiling face and fat throat, whose generous amplitude of waist and solid support of legs, augur well for the fare that awaits within. He rings the bell steadily with one hand, and with the other busily welcomes the passengers as though they were all old friends. Then how urgently he presses upon you a choice of good things! How distressed he is if you do not eat as heartily as he thinks you ought! How solicitous to assure you that there is time enough! And with what benignity, mildly protesting against the necessity, does he take your fifty cents! Do you wonder that he is known from one end of the Cotton States to the other, and that everybody loves “Cousin John” Thrasher?

That path to a man’s heart lies through his stomach, it is said, and this generous, easy-natured caterer has secured the right of way in this part of the world. Well, the point of this digression is that “Cousin John” is the original oldest inhabitant of Atlanta, because in 1839 he came here and built the first house. Soon after, other families settled at Terminus, and Mr. Thrasher opened a store; but he had little faith in the future of the village, for in 1842 “Cousin John” sold out, for a few hundreds, land now worth half a million or more, and departed.

“Cousin John” Thrasher earned his nickname because it seemed as if he or his wife were related to everyone in the state of Georgia. Not wanting to slight anyone he greeted everyone calling them cousin. Ingersoll was correct in his article that Thrasher arrived in the area that would become Terminus in 1839 to work on the railroad along with members of his crew of workmen. The small cluster of homes and a general store was nicknamed Thrasherville. A state historical marker stands on Marietta Street today noting the existence of the small community. Thrasher purchased land at what is today West End because rumor had it that the area would become the location for the zero-mile marker of the railroad. It was expected to become a business hub soon after the rails were put down, but delays in the rails and slow growth for a couple of years caused the impatient Thrasher to move on. It didn’t help that Lemuel P. Grant, also a railroad employee, donated land northeast of Whitehall for the railroad and the location of Terminus changed. Trasher sold his land at a significant loss and moved to Griffin. By 1844, Thrasher had moved back to what was by that time Marthasville and opened a store on Peachtree Street and was involved in opening the city’s first jail, first school, and the implementation of street cars. By 1870, Thrasher had moved along again and founded the city of Norcross naming it after his good friend Jonathan Norcross, the fourth mayor of Atlanta. By the time Ingersoll wrote his article for Harper’s in 1879 Thrasher had moved to Central, South Carolina where he maintained the restaurant mentioned by Ingersoll along the rail route from Atlanta to Washington, D.C.

While Ingersoll mentions “Cousin John Thrasher” as the first settler in what would become Atlanta, Hardy Ivy (1779-1842) is recognized today as the first person of European descent to permanently settle in what would be Atlanta when he purchased Land Lot 51 of the 14th District of what was then DeKalb County in 1833 building a double log cabin where the Marriott Marquis now stands at the corner of Courtland and Ellis Street. His wife’s brother, Richard Copeland Todd had settled nearby ten years earlier, but their land lot (17 of the 14th District) was outside the original Atlanta city limits when the city was incorporated by charter on December 29, 1847.

Patience fails to recount the growth of the settlement into a village, and the expansion of the village into the city which now calls itself a metropolis. It seems to have been essentially a pioneer town, owing its life wholly to the railways augmenting its size as new lines were opened and the business of the older roads increased. It was in 1842 that the first locomotive was seen in Atlanta. It did not come, as locomotives usually do, upon tracks laid up to that point, but was dragged across the country from Madison – then the terminus of the Georgia Railroad – upon a wagon drawn by sixteen mules.

To most of the rustics of that region a locomotive was a novel sight, and they gathered in a great crowd to witness its trial trip. The engineer saw a chance for a practical joke and claiming that he must have help to get the machine started for the first time, persuaded a great number of young men to push. Their first efforts were of no avail, and the crowd began to jeer at the engineer. But he induced them to make a second trial, and just as they were putting forth their strength prodigiously, he turned on the steam, and sprang from under them, leaving a sprawling and dusty crowd to take his place as the butt of rustic raillery.

This same year also witnessed the first sale of real estate by public auction, and one of those three town lots, bought then for an insignificant sum, has remained ever since in the hands of its original purchaser. It stands at the very centre of business, is covered by a block of brick buildings, and simply by increase of value now forms a snug fortune, giving a large annual yield to its owner.

Speculation in real estate soon began, however, when it was seen that the prediction of John C. Calhoun, made years before, that Atlanta would be the metropolis of Georgia, was about to be verified. Before many years fancy prices were asked for property, and rents required that were out of all proportion to value. It was supposed at first that the town would be built some distance west of its present location, and money was invested in that region. Then a shrewd landowner gave the site of the present Union passenger station, which was accepted by the railroads, bringing the centre of growth in the town over to that spot.

The Union passenger depot was located at what is now Wall Street between Pryor Street and Central Avenue and was the second Union depot at that location. The first was destroyed when Federal forces left Atlanta for the March to the Sea during the Civil War.

Thus, money was lost and made, but the city increased in population, got rid of the criminal element which had predominated in her earlier history, educated the country people, became enterprising, and in assuming the powers and legal privileges of a municipality, took to herself city-like ways and pride, and asserted herself to be the gate of the South, through which all commerce and emigration from the Northwest must pass.

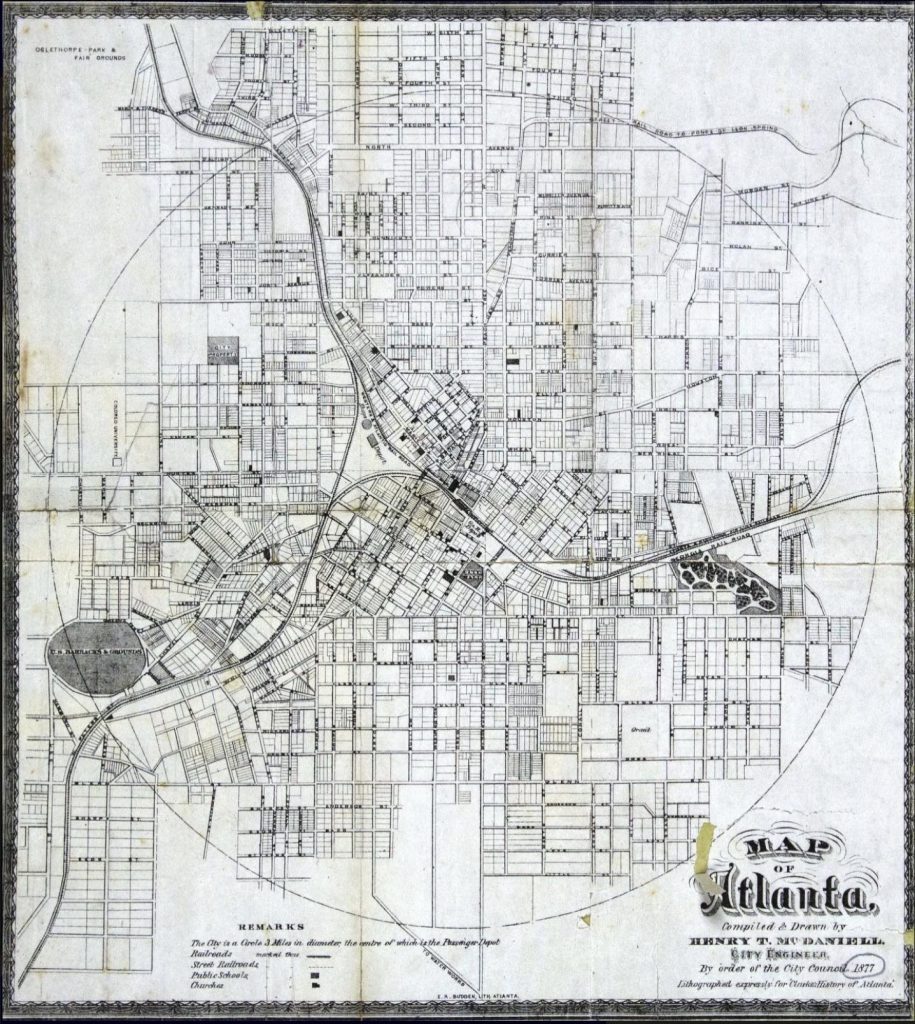

The map of Atlanta shows a circular line representing the boundary and having for its centre the railway station. The radius is one and a half miles. Within this circle (and somewhat also outside of it) is an array of streets so utterly irregular that you wonder how it was possible they ever could have been built up in that way. They go crooked where it would have been easier to go straight, show acute angles where a square corner could be made with less effort, and come to a sudden stop to run away into vacancy at the most unexpected points.

The map shown below of the city was created in 1877 two years before Ingersoll’s article for Harper’s.

The explanation is ready and reminds one of the Dutch cowpaths which are said to have determined the pattern of lower New York. It must be remembered that before the town existed the east-and-west road from Marietta to Decatur and beyond crossed at this point a road running north and south. They were such irregular and rambling turnpikes as are characteristic of this hilly region, and the village extended itself along them without any attempt at straightening. Reckoning from the junction, as habitation spread, the road to Marietta naturally became Marietta Street, while that leading in the opposite direction was soon called Decatur Street. Not far north of the village was an old justice-court ground (a State reservation) known as the Peach-tree Courthouse. A few miles southward stood a tavern, famous among all the teamsters through Georgia as White Hall. The two crooked roads leading north and south thus became Peachtree and Whitehall Streets; and in the case of the latter, it is told that the detour made by the stage-driver in going about a bad mud hole one winter is preserved by an elbow in the street. The bend is there, certainly, but the evidence of the “chuck-hole” has gone, or rather it is distributed throughout a mile of bad paving.

Then the three railway lines introduced new factors of discord, and finally the owners of the original half-dozen farms and land lots each laid out streets for himself entirely irrespective of his neighbor. The result is a city in some parts easy, and in others very difficult, to get about in, and which, from a bird’s or balloonist’s point of view, must appear very confused.

So, deriving her success from a multitude of business advantages and from her favorable situation in point of geography and climate, Atlanta has waxed great and powerful, and withal very attractive. All the evidence of busy life are around you, and only unless you are fresh from New York, Baltimore, or Chicago do you notice the provincial air. The telegraph pole at your elbow bears the little red box that carries the electric fire-alarm to ever-ready steamers and ladder trucks; the lamppost serves as standard for the mail drop-letter box; and a policeman in full uniform will assist you into a street car for any part of the city, if you need help of the “force.” There are banks, boards of trade, and business exchanges, and all the rest of the list of “modern conveniences,” from artificial ice to a Turkish bath or a complete system of telephonic communication.

Yet, however comfortable this is for the citizen, it has the drawback to the magazine writer and artist that it makes Atlanta too much like a hundred other large towns with which we are all acquainted in the North, and leaves less that is peculiar, characteristic, and picturesque than perhaps exists in any other city in the South. She looks to me more like a Western town, since her newness and enterprise hardly affiliate her with Augusta, Savannah, Mobile, and the rest of the sleepy cotton markets, whose growth, if they have any, is imperceptible, and whose pulse beats with only a faint flutter.

Yet there are certain features that strike the stranger’s eye. On Monday you may see tall, straight negro girls marching through the street carrying enormous bundles of soiled clothes upon their heads; or a man with a great stack of home-made, unpainted, and splint-bottomed chairs, out from among the white legs and rungs of which his black visage peers curiously; or urchins under baskets of flowers poised like crowns. Troops of little black boys, bare-footed, bare-headed, and ragged “to a degree,” as a certain English novelist is fond of expressing it, go about carrying bags in which they gather up rags in a manner wholly different from the New York chiffoniers [French for rag picker]. At certain corners stand farmers in scant clothing of homespun, and the most bucolic of manners, waiting for someone to buy for a dollar, or even half a dollar, the little load of wood piled up on the centre of a home-made wagon so diminutive that two men could walk away with the whole affair, while a third carried the mule under his arm.

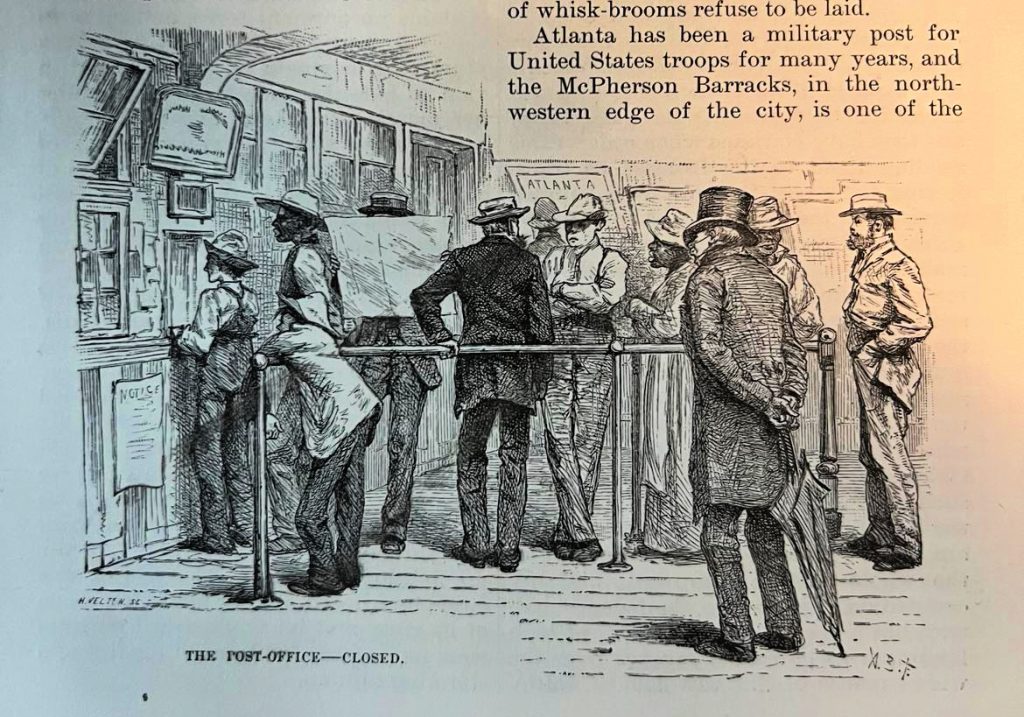

It is great fun, too, to go to the post-office after the arrival of the noon mails from the North. The office closes its windows, although it is the middle of the day, and devotes itself to the task of distribution. Meanwhile a crowd accumulate – most the rabble who get a letter about once in four weeks but mixed up of all sorts – and amuse themselves by making remarks not always complimentary to the rule of the office or stand patiently in line until the window opens. This delay in a post-office which supports the delivery system looks like a “relic”; but everybody has time enough in Georgia.

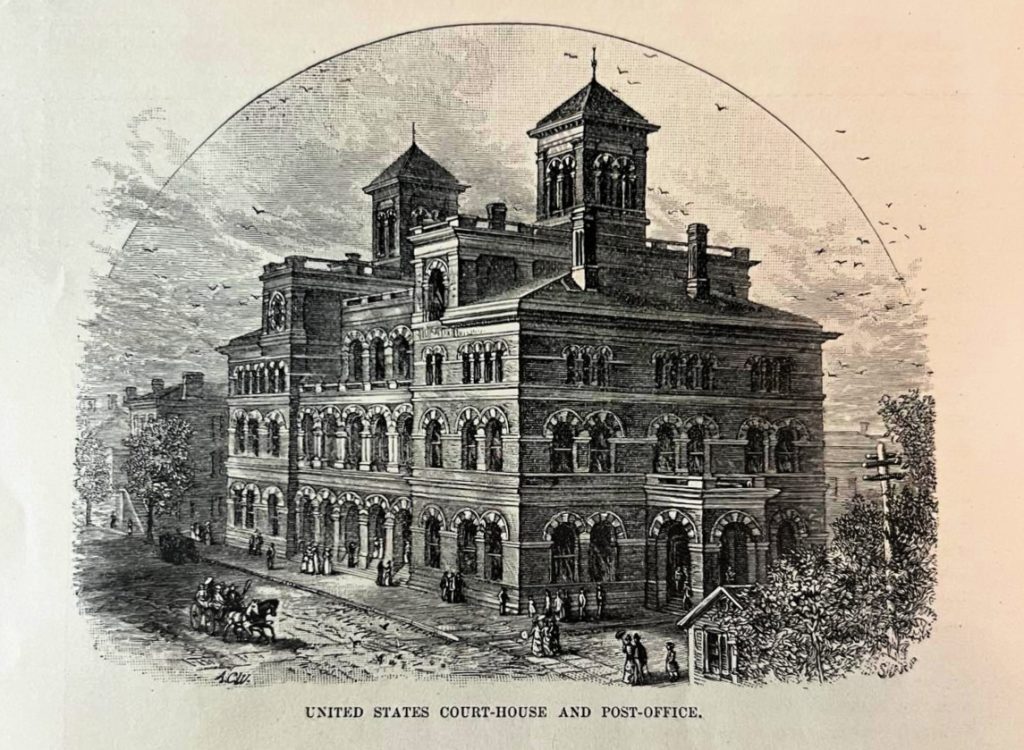

The U.S. Post Office and Customs House was located on Marietta Street, occupying the block bounded by Marietta, Fairlie, Walton and Forsyth Streets. It opened just a year before Ingersoll wrote his article. In 1910, the city would acquire the building and use it for Atlanta’s City Hall until 1930 when the building was demolished. In later years, the lot would be home to the Fulton National Bank building, and today it is home to the 55 Marietta Street Building.

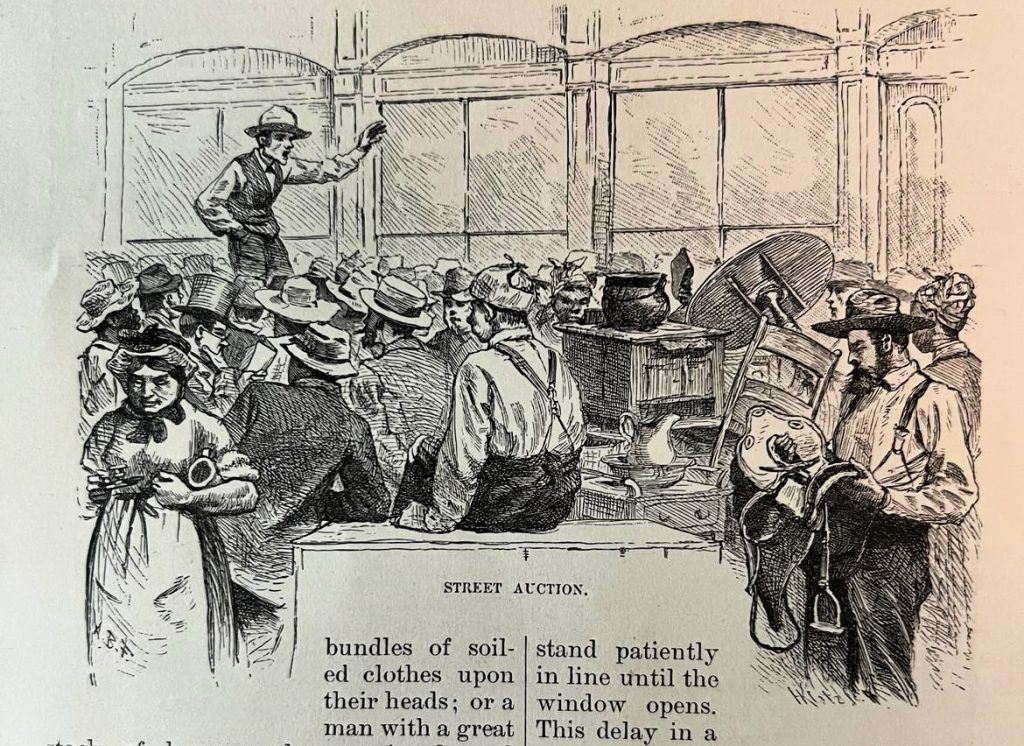

On certain days you will hear the beating of triangles, and have your attention attracted to the red flag of the curb-stone auctioneer, whose volubility will be heard above the din of traffic. These out-of-door auctions are always amusing, and the crowd of negroes, “poor whites,” and loungers that they gather afford an interesting study to the lover of physiognomy (assessing a person’s character/personality from their outer appearance – especially the face). It is like a bit of the Bowery or Chatham Street turned out of doors; but the articles sold are more miscellaneous and wretched. You may buy worn-out stoves and tables, second-hand bacon, muddy croquet sets, rubber hose of one kind and cotton hose of quite another, canary-birds, hat racks, baby carriages, old fruit jars, clothing, bath tubs, straw sun-bonnets and hats, squirrel cages, carpets, books, bedclothes made “befoh de wah,” sweet oil, saws, crockery, iron garden settees, ice cream freezers, saddles, window sashes – everything out of time and miserable, from a pair of snuffers to a horse and wagon alive and harnessed.

You can find part two of this article here.

Leave a Reply