A few days ago, I posted part one of this article you can find here.

In this article I’m providing the full text of an article that appeared in the December 1879 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine and was written by Ernest Ingersoll, a writer with Harper’s and Frank H. Taylor, “an artist of considerable reputation,” who were invited to visit the city and write an article by Evan Howell (1839-1905), editor-in-chief of The Atlanta Constitution.

At this point I would like to remind my readers that this article was written in 1879 in a time far different than today using language that was the accepted vernacular of the day. Rather than censor the article I wanted to include each paragraph as part of the historical record. However, it does contain offensive language or negative stereotypes reflecting the culture or language of a particular period or place.

Part one ended with a wonderful discussion of an outdoor auction. Part two begins with a discussion of a proposed market-house.

As yet Atlanta has no market-house; but it is proposed to build one at an early day, which shall be supported upon arches over the railroad track between Whitehall and Broad Streets. This would utilize (and handsomely too) a waste space; but if a locomotive should explode its boiler under there, wouldn’t the rise in breadstuffs be so sudden as to disturb the market?

Next Ingersoll describes dealing with the many brush boys and men that inhabited the city’s hotels trying to earn a few coins by using a whisk brush to clean a gentleman’s clothing. The brush man’s counterpart today might be those attempting to wash your window at a red light or hawking water bottles at every street corner.

Another event of the traveler’s life in Atlanta, which may or may not be amusing, is his contact with the brush fiend. This imp, or rather this species of imp, for there are many individuals, finds its home at the hotel, and there lies in wait for the unwary tourist, as the spider crouches in quiet anticipation of its muscine meal. You enter the door and walk halfway across the marble floor, when you feel a gentle stroke upon your shoulders, and turn your head to see an uplifted whisk in the hand of a darky, who grins in a conciliatory manner. But you harden your heart, proceed to the register, and lend your autograph in support of the imminent respectability of the house to which that much-blotted book is supposed to testify. The flourish is not yet from under your pen, when your modest hand-bag is seized, and down comes a broom upon your coat tail. A look fails to arrest the brush, and you flee. At the foot of the stairway is a shadowy corner. You are unsuspicious, not having yet learned to give it a wide berth. Just as your foot is upon the first stair, out leaps a whiskbroom and begins upon you. Now you must shout your menaces in language strong if you would be saved. Escaped this, you meet a fiend at the first landing. You watch him firmly grasping a brush as you approach, but you are ready. Fixing upon him your eagle eye, you say, “Lift that whisk-broom but one inch, and I pitch you down the stairs!” You turn your head as you go past, and never relax the deadly gleam of your eye until he is far behind. Finally, you reach your room, and the porter opens the door, sets down your baggage, raises the curtains, glances at the toilet arrangements, and being satisfied, civilly retires to the door, hesitates, seems to be trying to remember something, and softly asks, “Would you – like to have your coat – “ while out of his pocket steals the handle of a broom. The heavy matchbox is nearest, and it flies, while you look for the iron poker with one hand and feel for your pistol with the other. But the imp is used to this and has prudently banished. You bolt the door and find yourself in possession of the field; but he is the real victor, and until you either maim him for life or pay generous tribute of dimes, the brush fiend will torment, and the spirit of whiskbrooms refuse to be laid.

Atlanta has been a military post for United States troops for many years, and the McPherson Barracks in the northwestern edge of the city, is one of the points of interest for a stranger.

Ingersoll is not referring to Fort McPherson that many of us remember, but the original McPherson location on the land off Peters Street where Spelman College is today. McPherson Barracks was named for Union General James Birdseye McPherson who lost his life during the Battle of Atlanta on July 22, 1864. The military post was located there from 1867 through the early 1880s.

Money was appropriated in 1885 for a new military base and General Winfield Scott Hancock was tasked with choosing the new location – approximately 140 acres along the Central Railroad and the East Point wagon road. The new post was to be named for Hancock, but at point some those in control decided to keep the McPherson name. Completed in 1888, Fort McPherson grew to 487 acres before it was closed in 2011. The site continues to be in various stages of redevelopment.

Ingersoll goes on to describe the post saying, the Barracks are commodious, and the officers’ quarters, surrounded by neat gardens and hidden in masses of honeysuckle and wisteria, form attractive homes. A succession of regiments has held them, and they have bewailed when orders came sending them to the frontier or transferring their posts to some fever-haunted garrison on the seacoast. At present the Fifth Artillery are stationed here, and making themselves agreeable to the citizens, who find the presence of the garrison pleasant as well as profitable. From the Barracks, which are upon high ground, a wide and enchanting landscape spreads northward before the eye, terminating in the pale outlines of Tennessee mountains, where Lookout, Mission Ridge, Resaca, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga recall such exciting memories. Nearby towers the lofty double peak of Kennesaw Mountain, scene of the most severe fighting of the whole Atlanta campaign; and my companion, captain of a Confederate battery, has a bloody incident to tell of each landmark as he guides my eye over the wide expanse of this vast field of battle.

Imagination alone must fill the distance with the action which his stories relate; but as he explains the method of advance, the successive retreats and conquests by which the lines of attack were narrowed more and more upon the beleaguered city, the evidences of war become more apparent, and we can bring the remains of hostile operations actually before the eye, helping the fancy to picture the stirring scenes.

Down there in the valley stretches a long, low, irregular embankment, not yet overgrown with grass. That is the inner line of intrenchment which surrounded the city. Beyond it, appearing now and then in the second growth of woods, here lost in a valley, there enlarging into a fort upon a commanding hill top, is an outer line, and all about are scattered the little piles of earth thrown up at the rifle-pits, and the half-filled trenches which the pickets dug to protect themselves from sharp shooters and stray cannon-shot. Georgia seems to have little desire to hide her scars.

The red soil upturned by the soldier’s spade contains no dormant seeds and takes so slowly to a new planting that for fifteen years compassionate Nature has tried in vain to hide these marks of Mars under her mantle of herbage and wild shrubbery. Everywhere as you ride out of Atlanta you cross cordon after cordon of earthworks, pass through woods torn with round shot, where shells cut long pathways, and wander across fields sown with the leaden seed.

Gradually the city is extending itself beyond these red lines of embankments, and in twenty years their scant remains will become curiosities to the traveler.

Ingersoll is correct since one must be a Civil War expert to be able to identify battle locations as most only exist today within the text of a historical marker and lie underneath expressways and buildings.

In the rural districts, however, they bid fair to last a very long time. Five or six miles out on the Peachtree Road, for example, is a fort crowning a hill, whose lines and angles and full height are as well preserved today as though the work was thrown up only yesterday. It saw no fighting, however. The tide of war swept by without coming under the range of its guns, and its symmetrical outlines were never trampled beneath the feet of a storming column.

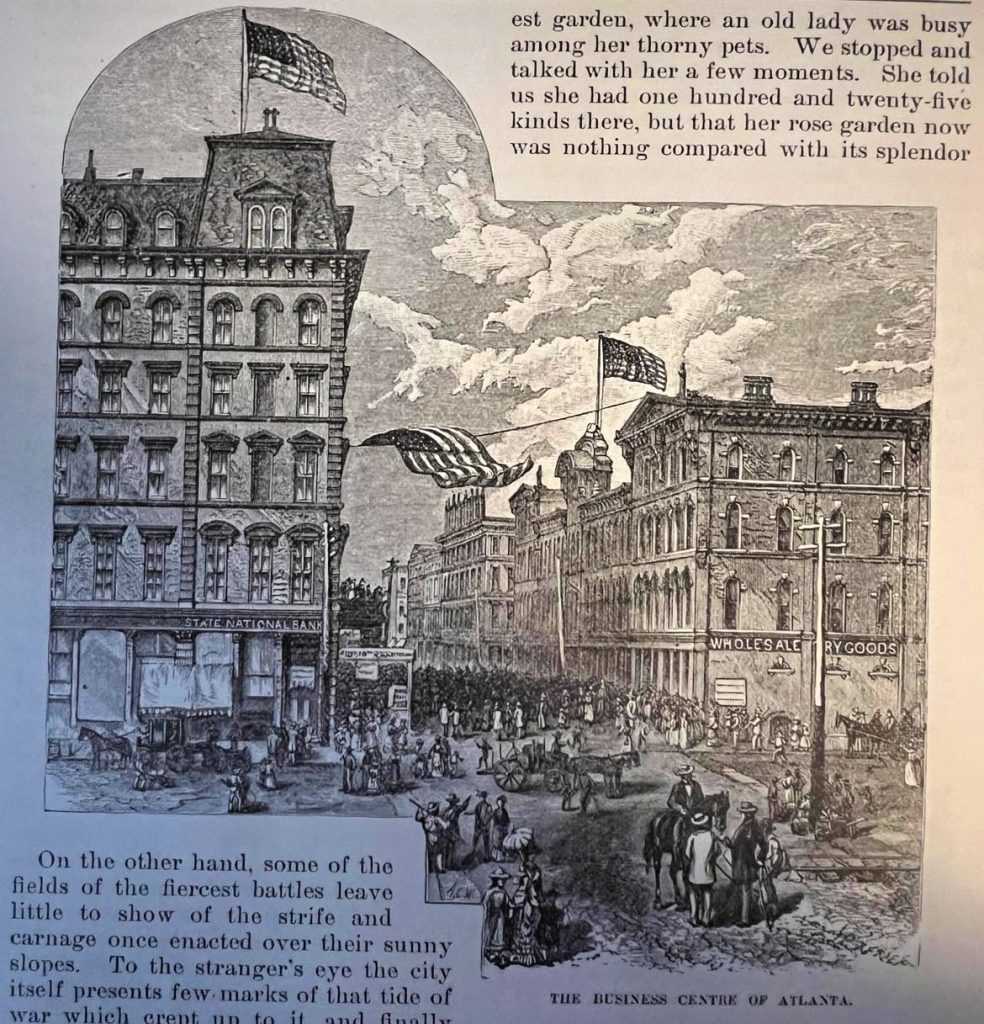

On the other hand, some of the fields of the fiercest battles leave little to show of the strife and carnage once enacted over their sunny slopes. To the stranger’s eye the city itself presents few marks of that tide of war which crept up to it, and finally surged so destructively across its whole area. There are ruins in the suburbs of what were once stately mansions, that have never been rebuilt, and you see scattered about the lonely stone chimneys that stand as monuments of a fireside forsaken, and a roof-tree [or ridge pole] long ago thrown down or burned away. The city itself has been rebuilt, and the houses that survived the shelling are already becoming dignified with historical interest.

Usually, it is some very insignificant incident which preserves the recollection of the conflict in particular places. Atlanta is a region of roses. A lover of them never tires of peeping over the fences and pausing before the conservatories in this early May season, so rich in the superb blossoms. One day we came to a modest garden, where an old lady was busy among her thorny pets. We stopped and talked with her a few moments. She told us she had one hundred and twenty-five kinds there, but that her rose garden now was nothing compared with its splendor before the war. “We had to leave during the siege,” she said; “the cannonading ruined the house, and the soldiers and all just spoiled my beautiful flower beds. I had a rare lily that was given to me by the royal gardener at Berlin, and that was killed; and I do believe, when I got back, of all the dreadful ruin, the loss of that flower hurt me the most.”It was in 1865 that the citizens and merchants came back to their desolate homes. Only one building, of all the commercial part of the town, had survived the flames. Business had to be built up from the very foundation again, and the energy with which this task was attempted shows the strong faith Atlanta men feel in their lively town. One of the first to return was the present president of the Board of Trade. He secured a cellar under the sole remaining building (on Alabama Street), paying $150 a month for its use, and began the produce and groceries trade, increasing his income by renting ground, privileges of a few feet square on his sidewalk at $20 a month each. Soon the owner of a corner lot on Whitehall Street built a brick building containing two store rooms. As soon as these were ready, our merchant and another moved in, paying $3,000 a year rent each, and giving half of it in advance, in order to aid the proprietor to go on with his construction. (The accommodations for which $6,000 a year was paid now rent for $1,500.) Thus, by mutual help and enterprise, together with a vast amount of personal labor, the ruins were replaced by substantial business edifices, new hotels of magnificent proportions were erected, churches more lofty in gable and spire arose upon the sites of those destroyed, and the vacant streets were refilled with people.

Atlanta became at once the distributing point for Western products, and now finds tributary to her a wide range of country. She handles a large portion of all the grain of Tennessee and Kentucky, besides much from the Upper Mississippi Valley. Much of the flour of the Northwestern mills comes into her warehouses and thence finds its way southward and eastward.

The same is true of the canned meats of Chicago, St. Louis, and Cincinnati packing houses: this is a very important item of her wholesale business. The provision men naturally were the first to obtain foothold in the new town. After them came the dry goods people. Most of them began in a very modest way – brought their goods tied up in a blanket almost – yet now the jobbing trade in dry goods alone amounts to some millions in dollars annually. No tobacco can be grown in the vicinity of Atlanta; hence she is without tobacco factories; but she used to handle an enormous quantity of it, and there are half a dozen firms who deal wholly in it now. It was found that Atlanta’s dry, equable climate, consequent upon her great altitude, made this point the safest place to keep stores of the grateful plant; it would not mold, as it is liable to do in a damp atmosphere. A few years ago, the revenue regulations were not as effective as at present. The practice of stencil plating packages of tobacco afforded easy means of evading the payment of duty, and great warehouses here were stored with “blockade” tobacco, from which Uncle Sam had derived very little, if any, pocket money. Enormous profits accrued, but the introduction of the stamp system put a stop to this, though Atlanta was left a very large legitimate business in storing and selling tobacco at wholesale.

Another source of prosperity to the city is cotton. The “cotton belt” of Georgia is a strip of country between here and Augusta. Years ago, the land became exhausted, and the cultivation of cotton came to be of small account. Then followed the discovery of the guano islands of Peru, and the subsequent invention of artificial fertilizers having similar qualities to the natural manure. These superphosphates are manufactured mainly in Boston, and the cost the farmer about forty dollars a ton. It was proved that by their use the worn-out cotton belt could be made to produce as bountiful crops in a series of five years as the Mississippi bottoms did; and, moreover, that cotton could be raised as far north as the foot of the Tennessee mountains. Atlanta, therefore, has come to be not only a great depot of supply for this guano, furnishing its vicinage a hundred thousand tons a year, but also the entrepôt of all the cotton produced within a circle of nearly two hundred miles. This cotton is bought mainly for foreign export and is shipped under through bills of lading to foreign ports, thus dodging the factors at New York, Savannah, and other coast cities. The business is not done on commission, but by buying and selling on a margin of profit.

There are other extensive business interests. Iron is mined nearby, and extensive foundries and rolling mills manufacture it. Great crops of corn and grain are raised throughout the central part of the state, which find their way into Atlanta distilleries, while her wine merchants are many and rich. She can make the best of brick and has a whole mountain of solid granite close by, with other building materials accessible and cheap. She sighs for only one more commercial advantage, namely, a railway to the coal regions of Alabama. Now her coal is largely supplied from ex-Governor Brown’s mines in the extreme northwestern corner of the state.

Within three years of this article the Georgia Pacific Railroad opened (November 1883) west through Douglasville, Villa Rica, and on into the very coal regions of Alabama mentioned and even further west.

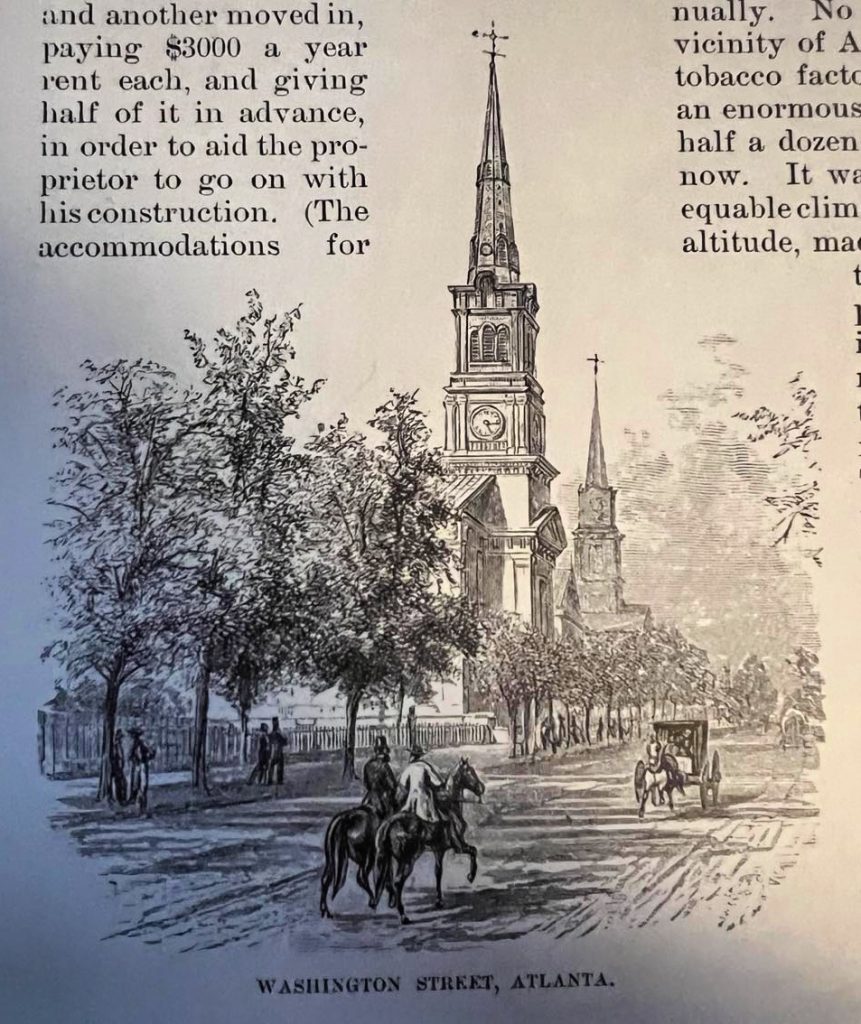

Looking away from the city, Barracks Hill furnishes a good vantage point, as I have already hinted; but to view the town itself, let me commend a ride along the new “boulevard” on the eastern edge. This broad, well-formed driveway follows the crest of one of the many ridges into which the surface of the country is cut up, and the solid squares of the city’s business houses, the lofty proportions of her great hostelries, the scores of spires of her handsome churches and school houses, and the charming, foliage-hidden avenues of her dwelling places and suburbs – all appear to the best advantage. No one will deny that she is attractive. The image below shows Washington Street which by the time this article was published in 1879 was one of the city’s finest residential streets and by the turn of the century included many mansions including the homes of governor and senator Joseph E. Brown, his brother, attorney Julius L. Brown, restaurant owner Henry R. Durand, fertilizer magnate and Standard Club co-founder Isaac Schoen. Later known as the Washington-Rawson neighborhood, the beautiful homes disappeared one by one. In more recent years the portions of the neighborhood were taken by the Downtown Connector while another section became home to the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium.

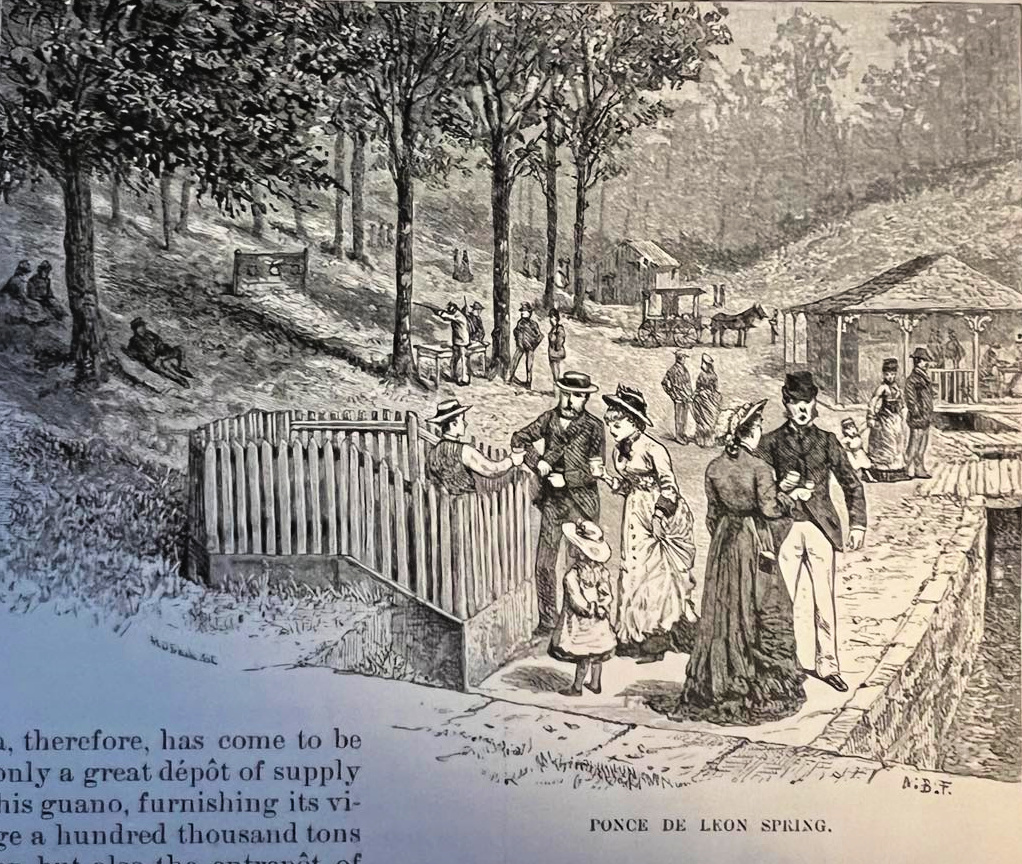

Just at the northern extremity of the boulevard is a little vale, upon which some slight cultivation has been attempted, mineral waters having been discovered bubbling out of the bank a few years ago. The name Ponce de Leon Spring was at once given to it, and the spot has become a pleasure resort, always visited in an afternoon’s drive. The horsecars run out there along a wonderful tramway, laid through a series of cuts and over a long trestlework, like a steam railroad. The waters have a sulfurous, nasty taste, and therefore is quite likely that they possess some at least of the medicinal properties ascribed to them. But I fancy the bracing violet-scented air, the tramping about under the trees, and the vigorous bowling over the ten-pins have more efficacy in accomplishing cures.

The horse car line became the famous thoroughfare we know today as Ponce de Leon Avenue. In the early 1900s, the spring was sold to developers who created an amusement park on the site, nicknaming it “the Coney Island of Atlanta.” By the 1920s, the park’s popularity had declined, and the land was sold to Sears, Roebuck and Company, who built their regional distribution and retail headquarters on the site. Today, the property is home to Ponce City Market.

On the outer side of the boulevard, as it follows the circle of the city boundary eastward and southward, runs a strip of tangled woodland, where two or three little streams meander in shadow and negligence. The ground is rough, and the authorities propose to take advantage of all this prettiness by annexing the vale and forming it into a park. It is certainly to be hoped that the scheme will be carried out. Atlanta has no park at all at present, excepting the grounds about the City Hall.

This is less to be deplored here, however, than in any other town you could find in the country, perhaps. One doesn’t appreciate how healthful is the position of this favored spot until he studies it. Atlanta stands upon an outmost spur of the Blue Ridge, eleven hundred feet about the sea – an altitude equaled by no other city of her size in the US. Her climate is equable and pleasant. “The nineties,” with which New Yorkers and Philadelphians are so familiar, are an almost unexplored region to Atlanta’s mercury, while in winter the southern latitudes preserve her from long or severe cold. The head waters of the Ocmulgee and several minor streams spring within her very boundary, and flow both east and west to the Atlantic and to the Gulf. Her drainage is therefore excellent. Men and woman do die there – no denying it; but epidemics are unheard of, and the locality is an island of health in the treacherous yellow-fever climate of the region. It is all dei gratia, however. No sanitary measures worthy of mention have ever been affected, or even tried; yet Atlanta is by no means a dirty city.

From a consideration of her healthfulness, we turn by antithesis to Oakland, the most artistic and beautifully cared for cemetery south of the oak groves. It shows a marked contrast to the decay and complete neglect of graveyards prevailing in all the rural towns. Here lie some thousands of dead Confederate soldiers, and a plain but enduring monument watches over the graves. At this grateful season the cemetery becomes a garden of flowers and is worth being seen for these alone. Here too, as elsewhere in Atlanta, the number and perfect growth of the hedges are very noticeable; but that finest of all Georgia’s hedge plants, the historic holly, is not often seen, though abundant in a wild state in all the hilly regions of this part of Georgia.

Public buildings in Atlanta are not imposing. The United States is just finishing a custom house, courtroom and post office in the shape of an attractive structure of brick and granite, modelled in a manner happily different from the ordinary government architecture. The Statehouse of Georgia is a square, business looking building on a prominent street, having an unofficial an air as any warehouse, and almost as roughly furnished within. The courthouse and City Hall form a large square building, surmounted by an accumulation of cupolas, reminding one of the touching ballad of “Kafoozalum,” where the hero appears as a “gentleman in three old tiles.” The site is high and beautiful and will before long be adorned by an ornamental building for public purposes.

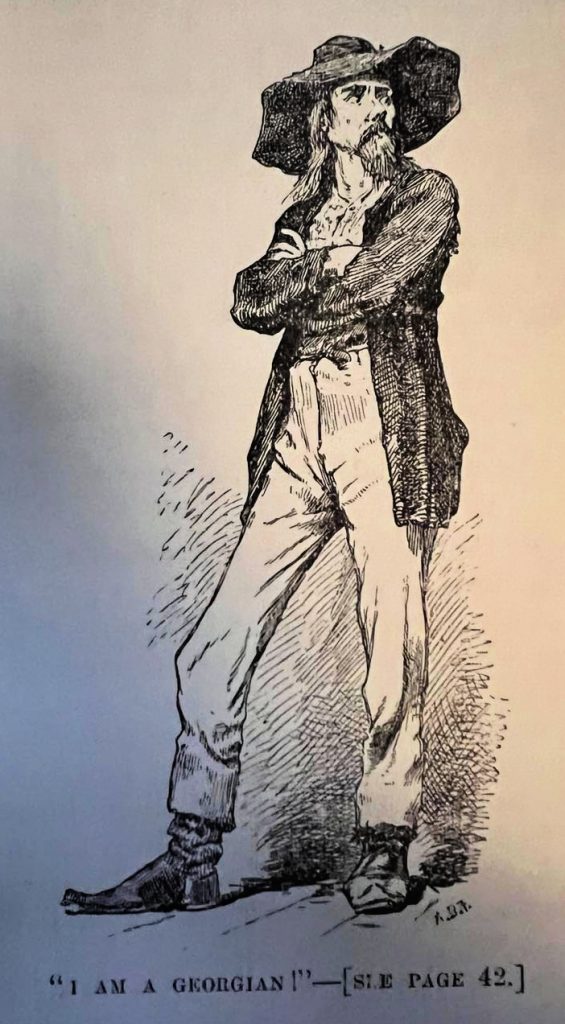

The site Ingersoll refers to is now home to the Georgia State Capitol Building.A noted trial for homicide was in progress, and I went to witness the proceedings. The courtroom was crowded to repletion with men, half of whom were smoking, though all had their hats off except an officer or two. The prisoner was in a happy mood, perhaps following Mark Tapley’s rule as to jollity under creditable circumstances. The lawyers and jury and everybody else were mixed up in the most picturesque style, and the judge’s bench had been seized upon as a good point of view by a dozen or more eager spectators. Notwithstanding these seemingly unfavorable conditions, good order was preserved. It was a good place to study faces. The audience was just such a throng as naturally would gather at a murder trial in the provinces. No city man or person of delicacy did more than glance in out of momentary curiosity, unless he had a direct part in the proceedings. It was interesting to watch these farmers and roughs, the consumption of unlimited quantities of tobacco in every shape forming a bond of union among them. I fancied an indefinable air hung over the assemblage which would not pervade a Northern crowd of similar character or want of character. Each one of these gaunt-limbed, high-cheeked, swarthy loungers seemed to say: “I may be poor, ignorant, diseased, and I may have come here in a two-wheeled cart with a mule in a rope harness and sat on the bottom because I was too lazy to arrange a seat; no doubt I’m an utterly useless Corn-cracker – but, Sir, ‘I am a Georgian!’” There have been persons in the halls of Parliament and on the floor of Congress who have attempted to assert themselves Englishmen and Americans, with the intent to be impressive in their patriotism, but I am perfectly sure none of them every really did make the asseveration half so strong as do these butternut-dyed Crackers by a single glance of the black eyes and a single toss of the shaggy head. Well, to be a Georgian is “something”; otherwise, these fellows would be hard put to it to define their position in the economy of nature.

Atlanta boasts, undoubtedly upon a firm basis of facts, that she offers the best educational privileges to her citizens of any community, large or small, south of “the line.” Unless Richmond, Virginia, be excepted, this is true. Atlanta has a complete system of graded and high schools, and they are fully attended. Then there are two or three commercial colleges, two “universities” for colored pupils who desire more than a common school education, two medical colleges, and an instructive display of the geological and agricultural resources of the State at the Statehouse.

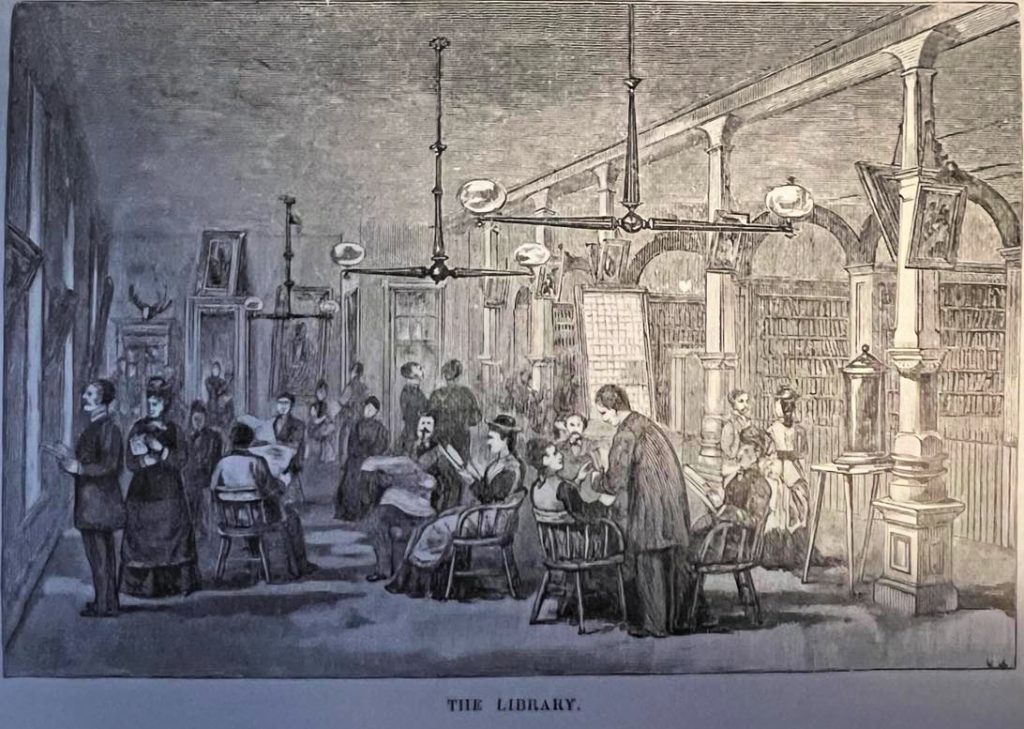

The Library of Atlanta is peculiarly southern in its associations. Around the walls of its handsome hall on Marietta Street are hung portraits and engravings of Confederate leaders, some in the gray uniform of the defeated “cause,” and some in the flowing robes with which painters love to enshroud their statesmen. Swords and banners and maps and other relics of war are profusely displayed. The library self-supporting, contains some thousands of well-selected and, what is more, well-read volumes, has chess rooms and reading rooms attached, and is a matter of just pride and comfort to the town.

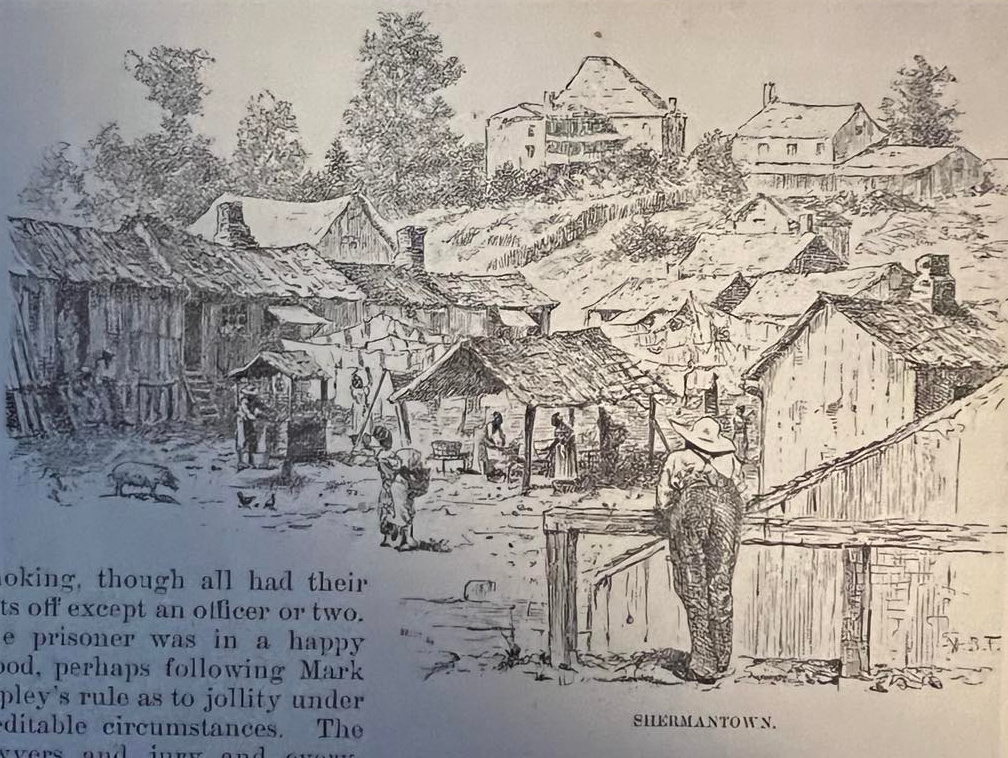

A feature of the city to which no well-ordered resident will be likely to direct a stranger’s attention is “Shermantown,” a random collection of huts forming a dense negro settlement in the heart of an otherwise attractive portion of the place. The women “take in washin’,”and the males, as far as our observation taught us, devote their time to the lordly occupation of sunning themselves. When General Sherman occupied Atlanta, it is said, barracks were located here; hence the name.

Shermantown still exists today in DeKalb County often described as a community at the base of Stone Mountain…one of DeKalb’s oldest African American communities found between the memorial and the downtown district. I encourage you to find out more about this historic area. There are several informative articles online.

Ingersoll continues, After dinner I take a cigar and saunter out. The streets are very quiet. People have hardly risen from their evening meal; and as I walk on out Peachtree Street, and the moon rises proof-bright towards the starry zenith, it is not easy to realize that I am in the midst of forty thousand busy men and women. Beautiful homes, varied, tasteful, sometimes grand in exterior appearance, luxurious in interior appointments, stand thickly on either side, embowered in trees, and surrounded by hedges and lawns, thickets of shrubbery, and parterres of flowers. Between the sidewalk and the hard but unpaved roadway stand lines of venerable shade trees, through who dense foliage the moonbeams struggle in uncertain manner and sketch a flickering mosaic of light and shadow across the path.

Attracted by music down a dark alleyway, I find five laborers, each black as the deuce of spades, sitting upon a circle of battered stools and soap boxes, and forming a “string” band, despite the inconsistency of a cornet. The whole neighborhood is crowded with happy darkies, and though the music is good, I choose the enchantment of distance. Not far away I strike another little circle of freedmen and discover that a guitar and a banjo are the attractions. On a vacant lot near the railway station a vendor of patent medicine has set up a rough platform and hung about it some flaring paraffine lamps. Two negroes – genuine negroes but corked in addition to make themselves blacker! – dressed in the regulation burlesque style familiar to us in cing jigs, reciting conundrums, and banging banjo, bones, and tambourine to the amusement of two or three hundred delighted darkies.

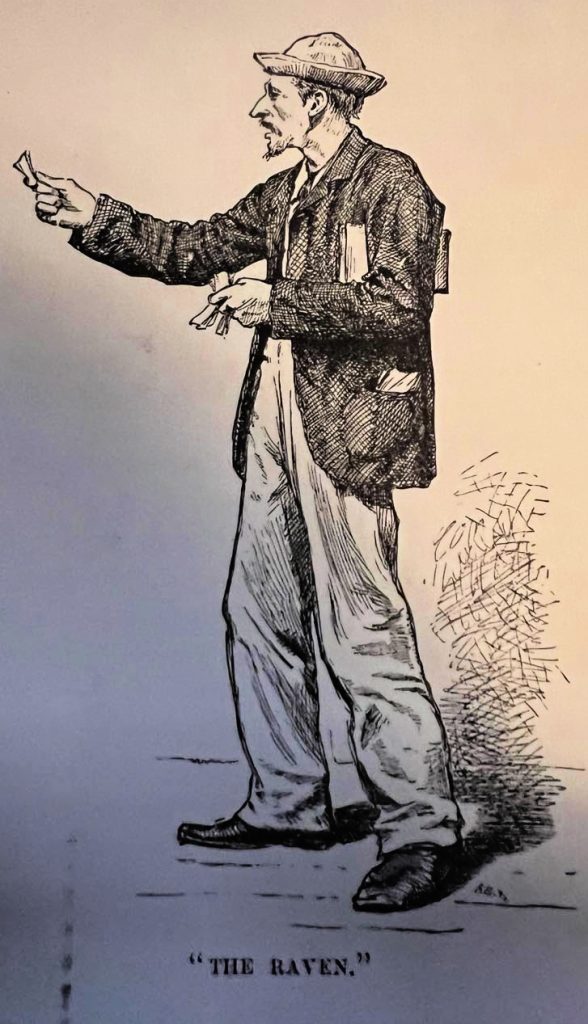

Ten o’clock arrives, and with many another lounger I saunter down to the station to see the trains from the north and east come in. Then the lights of the station are extinguished. Even the “Raven” who croaks his dismal forebodings of fatality, and sells accident policies to travelers, has disappeared.

I hope you have enjoyed this view of Atlanta from 1879. If you missed it, you can read part one here which also contains many drawings. While Ingersoll’s description of the city is interesting and amusing in certain instances, I also found it a bit disturbing such as his surprise to find the city had a library where the books appeared to have been read and his description of African Americans, but the language he uses are very common for 1879 no matter which area of the country the author called home.

As I mentioned at the beginning, Evan Howell invited Harpers Magazine to send someone to the city for a possible article, but I have not found any mention of the author, Ingersoll, and Tayor, the illustrator, or a mention of the article appearing in Harper’s December 1879 issue after its publication. I might have missed it, but at first glance no mention was made. Perhaps Howell and other powerful folks in Atlanta didn’t like the article.

Leave a Reply