As you might already be aware historical research interests me.

No surprise there, right?

I realize it might not be your thing, but it’s mine. I conduct the research in order to find the quirky things that draw people in, the hidden information that never makes it to the textbook or your eleventh grade history teacher’s lesson plan.

I use it to remind folks about things they know, but have filed them away somewhere in the dark recesses of their minds.

I use the research to write curriculum so other educators can share it with their students.

I use the research to feed my need to write, and learn.

I do the research to find little pieces of larger history puzzles I’m trying to put together, and that’s where the irony comes in. Most of the time I find little puzzle pieces here and there when I least expect them, most certainly when I’m NOT looking for them.

Sometimes those little puzzle pieces are monumental because they hold the key to solving a historical mystery.

I’ve never been that fortunate locate something like that, but Hugh Harrington has experienced the joy of a monumental find while looking for something else.

Hugh was on the hunt for information regarding a mass escape from a woman’s prison, so he was pouring over microfilmed issues of the Southern Recorder, a Milledgeville paper that was published during the Civil War. He happened upon a list of soldiers who had died at Brown Hospital during the last months of the Civil War.

The hospital, named for Governor Joseph Brown had been in Atlanta, but then moved under the direction of Dr. R.J. Massey to Milledgeville when General Sherman began marching south.

The list of soldiers had nothing to do with what Herrington was searching for, but he had hunch that the list might be important.

He knew there was a Confederate Memorial at Memory Hill Cemetery in Milledgeville to unknown dead. He knew this because he had been involved in indexing the many of the graves at the cemetery. He knew at least two of the soldiers were named in the Confederate section, and their names were on the same list he had just found in the newspaper archives.

It was more than a hunch. Herrington had stumbled upon the identities of the unknown soldiers – all of them.

Hugh Herrington did just what I would have done.

He went to the cemetery, walked to the memorial and announced to the men at rest there, “I know who you are…”

What a personal moment of joy for Mr. Herrington!

Then he met with members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and shared his discovery. They immediately agreed with him that he had found a resource to identify the graves.

He went through the list to determine which men were shipped home, and narrowed the list to 24 names. He determined they all died in August or September, 1864 while patients of the hospital. They all died of disease of one sort or another and they were all citizens of Georgia and part of the militia.

However, between September 6, 1864 when the newspaper article provided the names of the men who died and 1868 when the monument was erected folks didn’t remember a list existed, and the names had been lost all that time until Hugh Herrington happened to be looking for something else.

Astounding!

I have to wonder though if Mr. Herrington ever found anything on those wild women who broke out of prison.

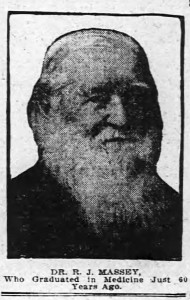

I’ve written about Dr. R.J. Massey, the head surgeon at Brown Hospital. He was instrumental in saving the State House in Milledgeville from Sherman’s torch and happened to live in Douglasville for a bit.

Through my months of research I’ve come to the conclusion that Douglas County history is packed with interesting people who contributed to our area and to our state in very important ways.

Some of those people were born in Campbell/Douglas County, lived here and died here like Joseph S. James. There are others who lived here for a time and then left to make their mark on the world like Hugh Watson, and still others who arrived in Douglasville for a brief time and then moved on like Dr. Robert Jehu Massey.

Dr. Massey was born near Madison, Georgia in October, 1828 and grew up near Penfield, Georgia. He received his degree from the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta and began a medical practice in Penfield before moving to Atlanta, Georgia. He married Sarah Elizabeth Copeland on June 16, 1850.

During the Civil War Dr. R. J. Massey assisted the Confederacy by serving as a surgeon. He often worked right in the field. In fact, an Atlanta Constitution article from 1908 concerning Dr. Massey’s 80th birthday has him recalling his efforts to save the life of General John Bell Hood when he was severely injured at Chickamauga. The article states, “When General Hood was operated on at the old Alexander bridge hospital, Dr. Massey administered the anesthetic.” In fact, several sources indicate Dr. Massey performed approximately 2,000 surgeries using anesthesia. Hood had been wounded so severely his right leg had to be amputated four inches below his hip. General Hood’s leg was sent along with him in the ambulance because it was thought Hood wouldn’t live much longer and at least his leg could be buried with him.

Of course, Hood did live to fight another day.

As the focus of the war shifted towards Atlanta Dr. Massey ended up at the Brown Hospital and helped it relocate further south to Milledgeville as Sherman’s men advanced on the city. Dr. Massey’s position was surgeon in charge.

Governor Brown and other state officials fled Milledgeville ahead of General Sherman’s army. The Union soldiers occupied the city of Milledgeville on November 23, 1864.

Lee B. Kennett in Marching through Georgia: the Story of Soldiers and Civilians during Sherman’s Campaign confirms Brown Hospital and Midway Hospital were the only public institutions still functioning when Sherman’s men entered the city.

Basically, you could say that Dr. Brown and the doctor in charge of the Midway Hospital were the only officials, of sorts, available to Sherman during his brief stay in Milledgeville.

Kennett recounts how Massey asked for Union guards at the hospital to keep soldiers from ransacking it. He had to do this more than once because the guards kept disappearing. Apparently Dr. Massey kept his eye on what the Union soldiers were doing in other parts of the city and in particular at the state house even though he had no power to stop them.

It would seem that Dr. Massey’s visibility during the brief Union occupation of Milledgeville and his interaction with General Sherman helped save the state house from the torch. Though the building was in great disarray when citizens returned to the city, important documents and records belonging to the state of Georgia were saved.

Years later the Georgia General Assembly acknowledged Dr. Massey’s actions.

Kennett also advises how General Sherman left twenty-eight of his injured men with Dr. Massey. Sherman told the doctor to give them a decent burial if the soldiers died, or if they lived to remand them over to the care of the prison at Andersonville. In return for taking care of the soldiers Dr. Massey received ten gallons of rye whiskey that had been discovered. Apparently the whiskey had been hidden by the owner of the Milledgeville Hotel in hopes the soldiers wouldn’t get it. Instead, Dr. Massey was able to use the whiskey at the hospital.

Another book, Civil War Milledgeville: Tales from the Confederate Capital of Georgia by Hugh T. Harrington discusses Dr. Massey’s efforts during the Milledgeville occupation and states Dr. Massey wrote his own articles in The Sunny South and The Atlanta Constitution regarding his war experiences that were published in the early 1900s.

Dr. Massey’s obituary from The Atlanta Constitution (March 19, 1915) states, “He possessed a wonderful memory, stored with vast knowledge of the pioneer history of the state, and his writings, which are written in a pleasing style dealt largely with this period.”

He was a great friend to Georgia’s Governor William J. Northern (1890-1894) and contributed over one hundred biographies to Northern’s book, Men of Mark in Georgia. The Library of Southern Literature also advises Dr. Massey wrote for Uncle Remus Magazine at frequent intervals.

After the war Dr. Massey practiced in Gainesville, and St. Simons, followed by a move to Douglasville. Dr. Massey’s son, Robert A. (Alexander) Massey, was an attorney, judge and Douglasville postmaster in the late 1800s.

In the book From Indian Trail to I-20 Fannie Mae Davis relates how Dr. Massey had a kitchen lab in his home which he used to concoct cures from herbs and roots he collected across the county. One such extract he marketed was Compound Georgia Sasparilla which was billed as ”The best, cheapest and most complete blood remedy in the world.” The extract could be bought directly from Dr. Massey at his office and at area stores for the sum of one dollar. Apparently, Dr. Massey also operated a drugstore in Austell before selling it to Dr. C.C. Garrett around the turn of the century.

While he lived in Douglasville Dr. Massey cultivated his love of history and exercised his writing skills. He was an early editor of The Weekly Star per Mrs. Davis. She states, “He…added great interest in the early paper which gave away to The New South a few years later and of several legends, giving the original source of the Skint Chestnut name. Dr. Massey’s story has been the most acceptable by lovers of local history.”

Thought he spent his last years writing Dr. Massey still practiced medicine. He returned to Atlanta in 1893 and served as the lead physician for the Confederate Soldier’s Home.

Dr. R.J. Massey’s grave can be found in Douglasville’s City Cemetery.

Leave a Reply