I believe making goals, creating a plan to meet those goals, and pursuing the plan is a worthy endeavor. It takes hard work and determination. It includes taking the time to give each move careful consideration and changing course when necessary. Unfortunately, we often get impatient. We get weary regarding the time it takes to reach our goals, and that’s when we are susceptible to taking an ill-timed short-cut.

Short-cuts can be a good thing, but then when it comes to our goals sometimes taking a short-cut results in ending up with something that is mediocre at best. I can think of at least one short-cut that resulted in tragic and horrifying results for one group of people.

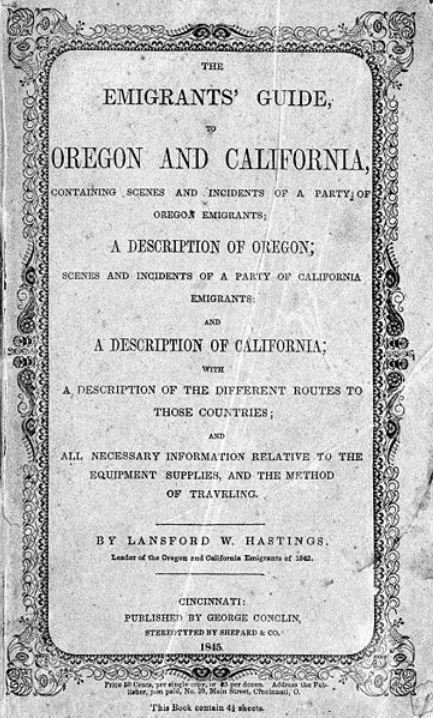

These words represent that tragic short-cut, “…The most direct path would be to leave the Oregon route, about two hundred miles east of Fort Hall; thence bearing west south-west, to the Salt Lake; and thence continuing down to the bay of San Francisco…”

It was these few words that sealed the fate of the Donner-Reed Party as they headed from Springfield, Illinois to California beginning in the Spring of 1846 along the Oregon Trail. Many other pioneer settlers had travelled the Oregon Trail before them and based on those experiences the members of the Donner-Reed Party knew the trip should take four to six months. They chose to take a short-cut which bypassed the established trails and instead crossed the Wasatch Range in the Rocky Mountains and the Great Salt Lake Desert in present-day Utah. This resulted in the Donner-Reed trip taking much longer and only forty-seven members of the original party of eighty-seven lived through the horrific ordeal.

Looking back on the entire trip those in charge of the Donner-Reed Party made many poor choices that plagued the trip but choosing to take what was described as a short-cut added 125 miles to the trip, resulted in the group being snowbound during the winter of 1846-1847 in the Sierra Nevada Mountain range, and resulted in some of the members resorting to cannibalism to survive. They ate the bodies of other members of their party who had died due to starvation, sickness, or from the extreme cold temperatures. They also ate the bodies of two Native American guides who were killed deliberately for the purpose of providing sustenance.

The short-cut was known as the Hastings Cutoff, a route which took travelers across what is now Utah to get to California, and the words I provided above came from the book The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California published in 1845 by Lansford Warren Hastings (1819–1870).

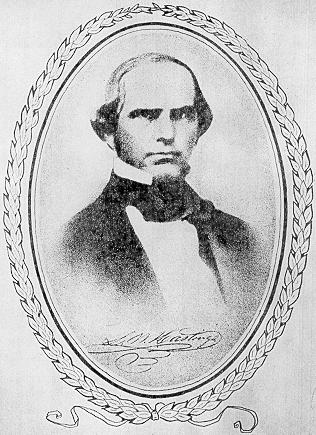

Hasting was born in Ohio to a prominent family that could trace their lineage in the United States back to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634 when their ancestor, Thomas Hastings, arrived from East Angelia in England. Though he was trained as a lawyer, Lansford Hastings wanted to explore the newly opened lands to the west. According to the California Trail Interpretive Center he was an ambitious man with dreams of building his own empire.

By 1842, Hastings was in Oregon where he represented pioneer settler, Dr. John McLoughlin regarding his claim that would eventually become Oregon City, the first incorporated city west of the Rocky Mountains.

By 1843, Hastings was in Alta California which through its history as a part of Spanish territory and later Mexican territory was also known as Upper California or New California. During the final decade of Mexican control this area would receive hundreds of American and European settlers mainly due to Hastings’ book I referenced above. It’s interesting to note that between 1840 and 1845 less than 500 travelled to California, but in 1846, after the book was published the number increased to 1,500. The book became a very popular trail guide even for those who did not use the Hastings Cut-Off.

Hastings wrote the book as one of his steps to reach his goals. He wanted to establish an independent Republic of California and obtain a high-ranking office for himself in the new government. The book’s purpose was to entice settlers to the area by promoting the land and healthy climate found on the California coast. The hope was that just by sheer numbers the American settlers could gain control of California. Hastings promoted the book heavily travelling from Ohio to New York giving lectures and offering the book for sale. He told would-be settlers they could expect opposition from the Mexican authorities in California. They would need to band together in large groups. He also advised he would be waiting for travelers at Fort Bridger in Wyoming, a vital resupply point for wagon trains along the Oregon Trail, to point them in the right direction.

Historians vary greatly when it comes to blaming Lansford Hastings for the tragedy that befell the Donner-Reed Party. Some sources state that even though Hastings had traveled the area extensively, he had never traveled the route of the cut-off. Others stated Hastings had travelled a portion of the cut-off route just days before the Donner-Reed Party decided to take the route. Still another source states he had attempted the route from Salt Lake City to Fort Bridger, but did so under great weather conditions, no time constraints, and did not cross the desert at all.

Even though the Hastings Cut-Off was not as well travelled as the main trail we know that two traveling parties – Harlan-Young and Hoppe-Lienhard – had successfully used the cut-off before the Donner-Reed Party made the turn at Fort Bridger, but they travelled much earlier in the year before the snowfalls grew worse.

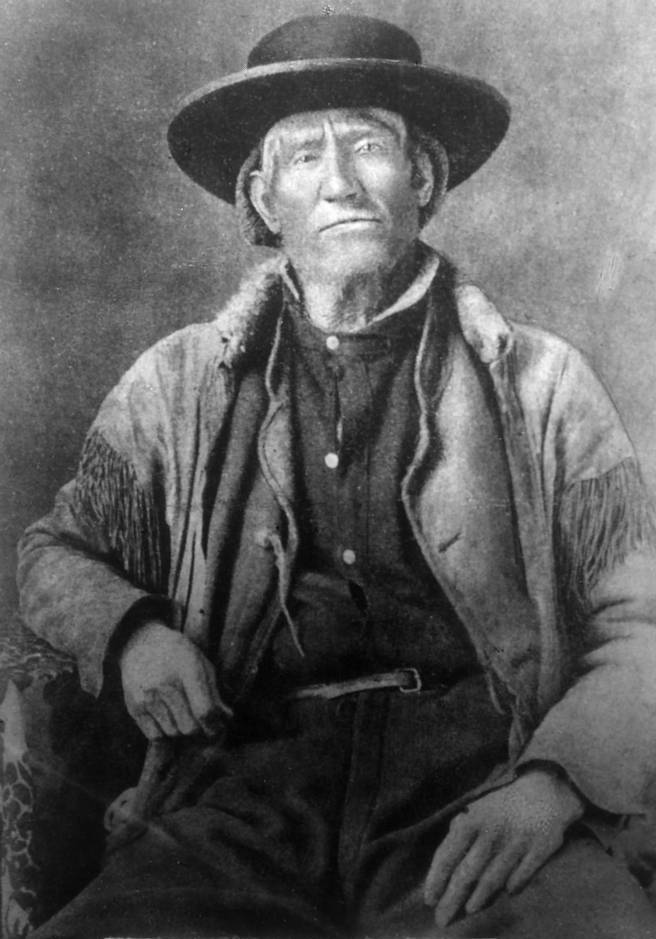

I’ve read accounts that mention Hastings would send riders out from Fort Bridger to meet up with caravans of travelers to give them letters to entice them to follow the Hastings Cut-Off. It is said these letters were often tacked to trees along the route advertising the cut-off miles before traveling pioneers would reach Fort Bridger. Some sources mention that even Jim Bridger himself was known to tell travelers the cut-off was smooth traveling.

The Republic of California that Lansford Hastings desired did finally come to be, but only for twenty-five days in 1846 during a rebellion against Mexican rule covertly encouraged by Savannah-born, U.S. Army Brevet Captain John C. Frémont, a friend of Lansford Hastings. The Republic ended when U.S. Soldiers arrived, and the process began to annex California as part of the United States. In case you have ever wondered why the current California state flag has a bear on it, now you know. In 1848, California was formally ceded to the United States under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and with that Lansford Hastings dream of an empire in California was over.

Hastings served as a captain in the California Battalion along with John C. Frémont during the Mexican American War (1846-1848) and as a delegate to the California Constitutional Convention in 1849, but by the late 1850s he had moved his family to Yuma, Arizona where he practiced law, served as postmaster and a territorial judge.

Lansford Hastings wasn’t through with California, however. Though he was born a Yankee, Hastings sided with the Confederacy. In 1864, he traveled to Richmond, Virginia and met with Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy, to present a new scheme. This time the goal was to work to gain citizen support to separate California from the Union and join the Confederacy. The scheme is remembered as the Hastings Plot.

President Davis promoted Hastings to the rank of major and gave him permission to form a military unit in Arizona that would work to defend California. The scheme fell apart as the war soon ended.

Following the war Hastings saw opportunity again. This time he focused on the former Confederates who were having a hard time accepting the loss in war and the subsequent time known as Reconstruction. Many of these former Confederates were leaving the United States for Brazil. Hastings traveled to Brazil and met with Emperor Dom Pedro II. Hastings soon had permission to form a colony of ex-Confederates or Confederados as they are known in Brazil today and chose a tract of land along the Amazon River. The Emperor offered cheap land and slavery would remain legal in Brazil through 1888. The Emperor hoped the Confederados would provide expertise in producing cotton.

Hasting returned to the United States where he followed many of the same steps he used in his California scheme. First, Hastings wrote a book titled The Emigrants Guide to Brazil published in 1867 to begin attracting even more dissatisfied families, but just when it seemed Hasting’s dream of having high office in an empire he created seemed to becoming true, he died while at St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands where he was in the process of conducting a shipload of settlers to his colony in Brazil.

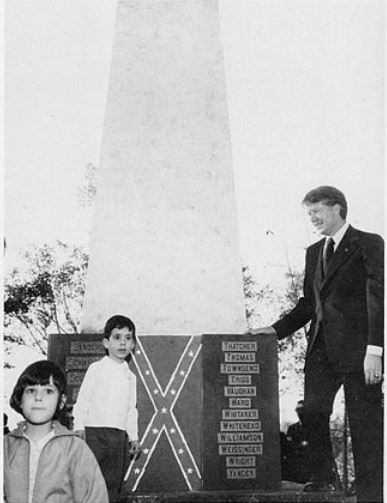

While Lansford Hastings never achieved his dream of retaining high government office, he did have a success in that today thousands of citizens of Brazil can trace their linage back to the Confederados who numbered at 115 in 1867, but in the next several years it is estimated over 20,000 Americans had joined the colony of Confederados in the San Paulo region of Brazil – a community known as Americana.

Since then festivals have been held complete with hoop skirts, Confederate uniforms, and food of the American South infused with that of Brazil. They also have dances and music that give a nod to the American South. Many southern Americans can claim kin with the Confederate descendants in Brazil including former First Lady Rosalyn Carter. Her great uncle, W.S. Wise, was one of the first Confederados in Brazil. The Carters traveled to Brazil in 1972 and paid a visit to the uncle’s gravesite. President Carter stated at the time the Confederate descendants sounded and looked like American southerners.

There are several books that discuss Lansford Hastings and his role with the Donner-Reed Party tragedy. One is Salt & Snow: Lansford W. Hastings, the Donner Party, and the Haste to Blame by Eugene R. Hart. A book that discusses the Confederados is by Cyrus B. Dawsey titled The Confederados: Old South Immigrants in Brazil.

Leave a Reply