I went by the 4-H Camp on Herschel Road in College Park often when I was a little girl. I never went there myself, but it appeared to be an interesting place. From the road you could see a baseball field. My mother’s car turned in a time or two to pick up Dear Sister who was there doing big sister stuff of some description.

That’s my limited knowledge of the 4-H Camp. Since then I’ve discovered through friends who also grew up in the area that its formal name was Camp Truitt, but recently I came across this postcard.

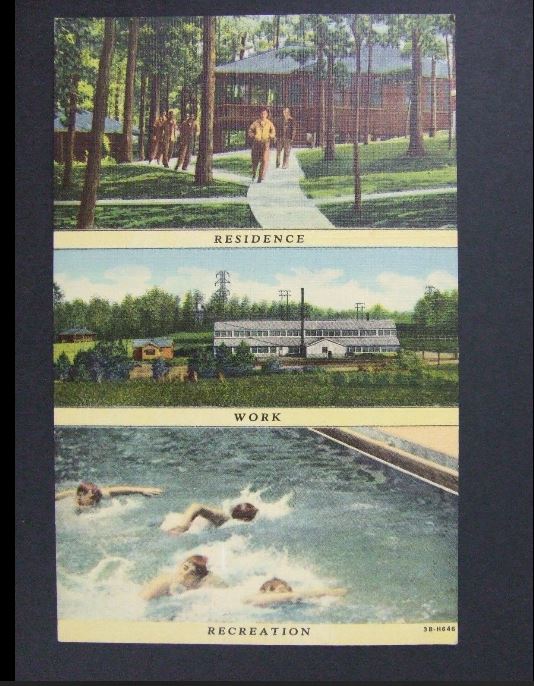

On the front are three different views with the words “Residence,” “Work,” and “Recreation.”

The description on the reverse side says, “Resident war training. Project of the National Youth Administration at College Park, Georgia. War training is offered in aircraft, sheet metal, foundry, machine, radio, and welding shops.”

From my teaching days I knew the National Youth Administration was originally part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal and focused primarily on work and education for young people between the ages of 16 and 25.

Think vocational school on steroids.

By 1942, the NYA was transferred to the War Manpower Commission, and by 1943 the program was discontinued.

In 1938, the federal government allocated $44,000 (another $34,000 had already been spent) that would go towards completing a 4-H Camp at Chapman Springs, near College Park. Fulton County would supply the rest of the funds for the Chapman Springs project transforming it into an industrial training school to provide skilled mechanics and machine operators for the Atlanta region. The camp would be made available to the 4-H Clubs and youth farm organizations during the summer months for use as a camp and workshop. A concrete swimming pool and several frame buildings had already been built. A large central building, a dining hall and residence cottages would complete the institution.

In the late 1930s, Fulton County would supply the rest of the funds for the Chapman Springs project transforming it into an industrial training school to provide skilled mechanics and machine operators for the Atlanta region.

The camp would be made available to the 4-H Clubs and youth farm organizations during the summer months for use as a camp and workshop. A concrete swimming pool and several frame buildings already have been built. A large central building with a raftered ceiling, a dining hall and residence cottages would complete the institution.

One of the newspaper articles I accessed mention the land for the camp had been donated by John Chapman, and the mention of him and Chapman Springs certainly made sense to me since one of the streets intersecting Herschel Road close to the camp was Chapman Springs Road. The road fronted Jamestown Shopping Center which comes up in the top ten places my mother went when she was running errands. I spent a bunch of younger years at the Woolworth, Kroger, Jacob’s Pharmacy, and Nick’s Bakery that made up just a fraction of the businesses located at Jamestown. Behind the shopping center was a park with a slide and other things called Chapman Springs Park.

Well, I was intrigued enough to go forward with more research wanting to know more about John Chapman and Chapman Springs. Twenty-seven typed pages later was all it took for me to make a few major connections to details I remembered from my childhood.

The children in the photo below are from Orchard Knob and have just arrive at Camp Truitt for 4-H camp.

Beginning in 1938 and for the next few years Camp Truitt/Chapman Springs had a duel purpose. During the summer the place was filled with different groups of at least 40 youngsters who had received free scholarships to the camp as a reward for carrying out wild life projects and keeping records on the work. Other children would arrive at the camp who paid a small fee. During the week campers would hear talks by noted conservationists and see moving pictures dealing with wild life. During the other nine months of the year the property would be used as a war training center.

Next, I went on a hunt for John Chapman, and my search brought me to this place you see in the photo below.

Well, this certainly rang some bells with me. I lived just a stone’s throw from the cemetery for the Red Oak Christian Church also known as the Red Oak Cemetery. During my elementary school years, I probably passed this cemetery at least twice a day and depending what else was going on as many as six times a day. I was “familiar” with the cemetery and the two mausoleums on the property. The Chapman structure sits right on the road as the picture shows. I always wondered about it. Who was there? Why did they have a “house” while the other graves didn’t?

Of course, as I aged I finally figured out what the “houses” were for, but it took me fifty years to discover who was buried there. It seems John Chapman and I have had a date for a very long time for me to write about his story.

The Chapman mausoleum contains the graves of Berry Edward Chapman (1849-1885), his wife Clarinda Dorcas (Trimble) Chapman (1846 – >>>), their son John McAfee Chapman (1878-1947) and his wife Martha L. (Stevens) Chapman (1897-1978).

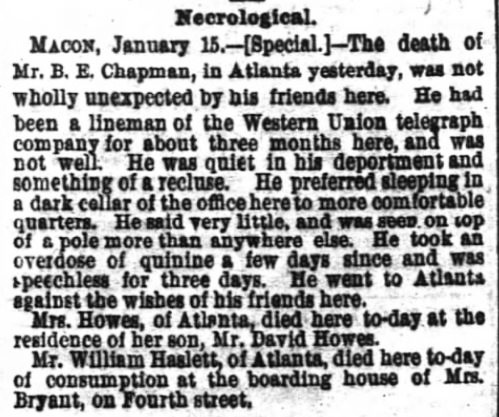

Berry Edward Chapman was born in Itwamba, Mississippi, but by 1860 he was living in Henry County with his mother and sisters stating his occupation was telegraph repairs. He married Clarinda Dorcas Trimble in January 1876. Two years later the young married couple were in Rome, Georgia when their son John was born and then moved to Campbell County at Red Oak.

I was able to discover that at the time of his death Berry Edward Chapman was doing something with the telegraph lines between Macon and Atlanta. In January 1885, he fell ill, took an overdose of quinine and died leaving his wife and young seven-year-old son to fend for themselves. The mother and son end up in Atlanta where she took in boarders.

Once he was old enough John Chapman began to work for Frank Edmondson, a well-known Atlanta pharmacist in the 1890s. Edmondson was involved in the new bicycle craze especially the new sport of bicycle racing, and he introduced it to John Chapman who became one of the best-known Atlanta “wheelmen” that you’ve never heard of!

From 1896 to 1902 John Chapman was a very active wheelman winning several national races and often described as a popular and plucky racer. In the beginning many of the Atlanta bicycle races were held at the race track located at Piedmont Park. You can still see the outlines of the large track located where the baseball diamonds are today from the air. The race track dates to 1887 when the Gentlemen’s Driving Club purchased some land where the park sits today and built the track – a half mile oval originally for horse racing.

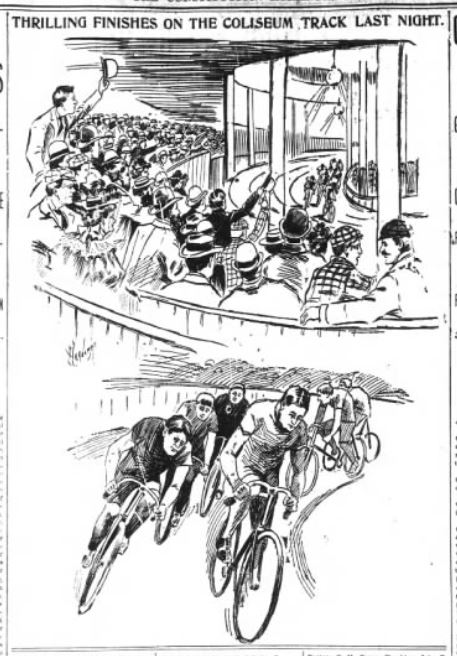

In 1895, the property was developed for the Cotton States & International Exposition. Dozens of temporary buildings were erected, but a few permanent buildings were also built including a coliseum with a dirt track where bicycle races were held during the Exposition. Prior to races the track had to be rolled and scraped until it was smooth as a floor. If the weather was favorable bikers logged some fast times.

The earliest I can find mention of John Chapman and his racing career comes at the end of June 1895 when he took second place in a race where an estimated two thousand people yelled themselves hoarse as the riders came around the last curve of a five-hour race covering 123 miles. By the final heat as the riders began their world record breaking spurt everyone was on their feet and pandemonium reigned.

Here’s a little of what happened from newspaper reports:

Con Baker took the lead and with a mighty effort led the racers around for one lap. Russell Walthour was playing a close second, Carpenter third, and Chapman, fourth…Suddenly, Chapman sprang into second place, and then within five feet of the line Chapman forced his wheel just a fraction in front of Baker’s. The pistol fired, and the last heat of the five hours’ race was finished, the big race had been won and lost.

Not a person in the large grandstand took seats for fully two minutes after the pistol fired. They were asking the question who won. The track filled up with the crowd and several accidents were narrowly averted. The judges in the stand were in consultation. The position of the three leaders were so close that only those sitting in a direct line with the tape were able to tell who crossed first.

It was Jack Prince, a retired English bicycle racer and promoter, who announced Chapman had crossed the tape first and the Atlanta boy was given an ovation. In 1897, Prince would build a wooden velodrome bicycle track inside the Piedmont Park Coliseum which resulted in even faster and more dangerous races as well as larger crowds of spectators.

Local newspapers described the track as an “odd affair, one-sixth of a mile in length…twenty feet wide and banked or sloped up ten feet at the curves.” The track was so slanted riders had to maintain a very high speed to keep from sliding down. It was noted that “when six men dashed around the curves at a two-minute gait and all so close together that one large umbrella would almost cover them.”

One race, attended by 3,000 fans, in the new coliseum building was described thusly:

Long before the first race was scheduled the scene was all activity. In the grandstand the audience was moving to and fro, while securing seats, and around the track were speeding a number of racers, togged out in their scanty but picturesque costumes. These multi-colored sweaters and knickerbockers were one of the features of the evening. Some of the outfits were marvels at construction and general appearance. All the colors of the rainbow were there, made up into many strange combinations…

….Only two of the racers were hurt. In the final heat of the evening O.L. Stevens of New York, took a bad tumble on the first turn. He lay stunned for an instant, but was quickly attended to by his trainer, and aside from a few bruises and a sprained arm, escaped unhurt.

At the finish of the final of the second race, John Chapman, the Atlanta boy, took a header from his machine. He was not badly hurt and quickly jumped to his feet…

While all the racing men were required to be members of the League of American Wheelmen, they didn’t always get along on or off the track. A few days after the race I describe above it was apparent that something out of the ordinary was taking place in the coliseum dressing room after several heats had been run when several policemen rushed through the gateway and disappeared into the dressing room. Apparently, the excitement had been caused by a scrap between Al Newhouse of Buffalo and John Chapman. Newhouse claimed he had been fouled by the Atlanta man and demanded satisfaction by rushing at Chapman. As he did, a score of attendants seized the two men, and all was over.

Whether this rattled Chapman or not, I do not know, but later in the evening he took what was described as a fearful tumble just as he reached the tape at the finish. About 20 feet before the finish line was reached, Chapman’s front wheel “kissed” or rubbed against the rear wheel of one of the leaders. The effect was felt at once, but on account of the momentum of the riders the fall did not occur until the line was reached. It is a significant fact, however, that Chapman did not race the second night.

One of the Atlanta wheelmen Chapman always tried to best was his friend Bob Walthour. It had long been the ambition of every professional in Atlanta to show Walthour his rear wheel for no other reason than he had always been the best of the lot. Walthour’s training regimen was so intense he would wear a sack of sand tied to each leg so that when they were taken off and he went into race, his legs would feel light and eager for the pedals. Many felt that if Walthour could be beat, John Chapman was the man to do it simply because of his talent to spring to the front very rapidly.

By September 1899, Chapman was racing in Salt Lake City, Utah where he lowered the world’s record for a paced mile on an eight-lap track to 1 minute, 47 seconds. Chapman also broke the world’s record for three-quarters of a mile handicap professional race, going the distance in the fast time of 1:29 from the scratch. Chapman returned to Atlanta in October 1899 with two gold medals, a belt full of bicycle riders’ scalps and some fine records to his credit.

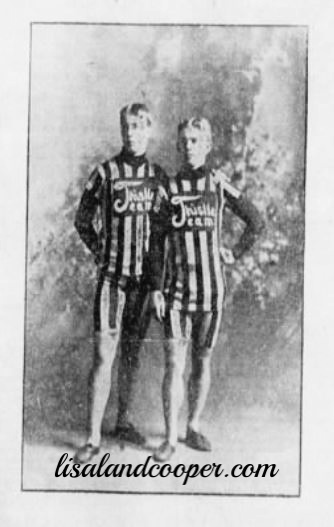

In March 1900, Chapman won the 50-mile paced race and handily broke the world’s record at Los Angeles in 1 hour, 37 minutes, and 19 second making him the 50-mile champion of America. A couple of months later the picture I’ve placed below of John Chapman and Iver Lawson hit the papers. The two had teamed up calling their tandem bicycle the “Devil Catcher,” and claimed the distinction of wining six tandem races and being undefeated.

As Chapman grew older, he began to see how he could make more money promoting the sport of bicycle racing and representing new talent. From 1907 to 1937 he was a leading promoter of the sport operating tracks in New York, New Jersey, and Utah. He operated the New York and Newark, New Jersey velodromes where outdoor racing was staged at night.

It was in New Jersey where Chapman met his wife, Martha, who was born at Madison, New Jersey. The two traveled to Red Oak where they were married at the Red Oak Christian Church on December 3, 1918 with several friends and family members in attendance.

John Chapman also managed the original Madison Square Garden for a time where his talents spread to promoting boxing matches and other events. It was at Madison Square Garden (the original structure is pictured below) where he began and promoted the six-day international bike races. During these races two-man teams would ride non-stop for six days eating, sleeping at the track one resting while the other rides. Many credit John Chapman with the growth of bicycle racing and refer to him as the “Czar of Cycling.”

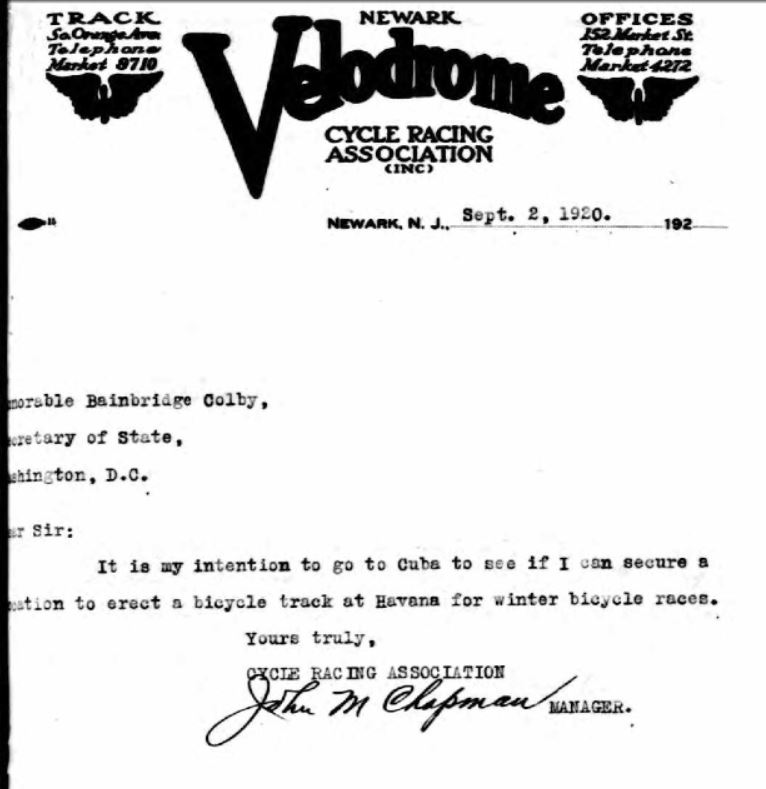

In his role of president for the National Cycle Association from 1915 to 1937 Chapman often traveled to Europe to locate and secure new talent and the sport’s greatest names of the sport. He also made many young American riders into champions. This letter shows Chapman’s intention to travel to Cuba.

These pictures of Chapman and his wife are from one of their passport applications during the 1920s.

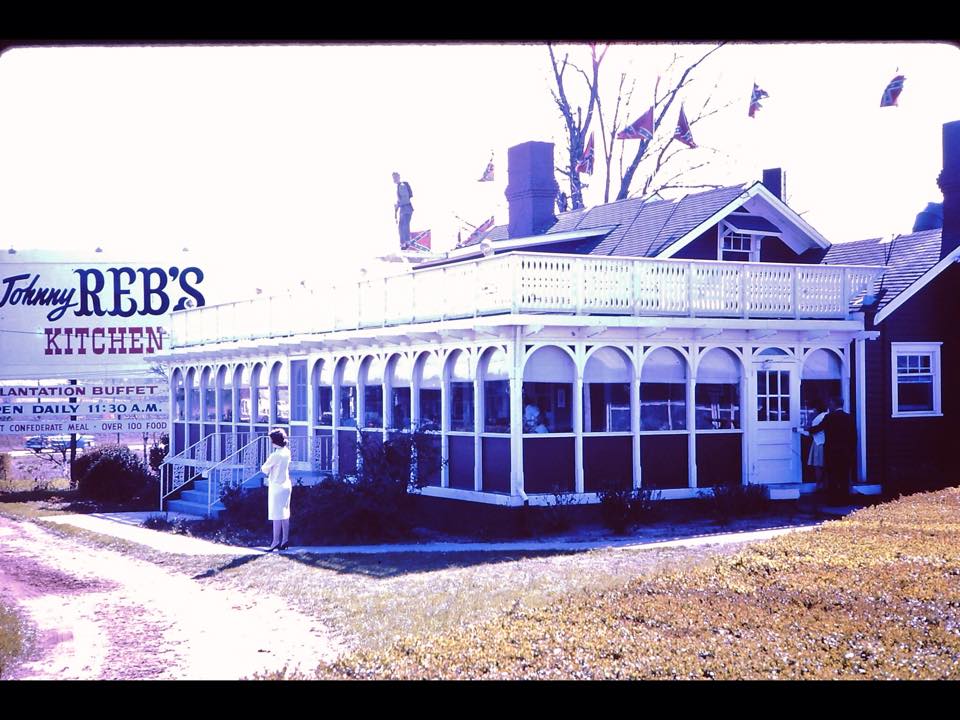

Later in life, Chapman divided his time between his home in Summit, New Jersey and Georgia where he maintained two farms. The property along Chapman Springs Road served as his residence, and as a child I had been inside it many times but had no idea who had once owned the property. Yes, the revamped home that served as the Johnny Reb’s Restaurant along Roosevelt Highway was John Chapman’s home.

Chapman also maintained a dairy in Palmetto which he named Velodrome Dairy as a nod to the profession that made him a wealthy man. The dairy sat on 825 acres where 85 head of choice cows were milked and raised in what was described as perfect conditions.

The silo at the Velodrome Dairy Farm was one of the largest in the area and had a capacity of 204 tons of feed that was raised right on the property. There were large dairy barns and a milk house which could be seen by passengers traveling on the railroad along Roosevelt Highway/Highway 29 or as it was referred to in a 1930 article “the highway to LaGrange.” One of the barns had “Velodrome Dairy” painted on the roof in large letters.

The dairy employed 30 people and was managed by J.L. Alexander. There was a fleet of trucks that delivered milk to all parts of Atlanta, College Park, and East Point. The photo below shows John Chapman (right) looking over one of his dairy cows with “Pa” Stribling, father and manager of boxers Young Stribling and Herbert “Baby” Stribling. The Stribling family story is an interesting one on its own, and I encourage you to look it up.

In a 1935 column in the Constitution, Ralph McGill knew many did not know about Chapman’s rise to fame several years earlier and tried to educate a new generation regarding the dairy name by saying, “It’s an old fashioned name, dating back to the gay nineties when velodromes were in almost every town and when the city fathers were making speed laws to stop the ‘scorchers’ on bicycles who were making 20 miles an hour through town, but few people know that Atlanta supplied the man who made six-day bike racing in America a million dollar business, but that’s why John Chapman’s farm near Palmetto has Velodrome painted on the dairy roof.”

McGill continued by discussing John Chapman’s modesty and his habit of keeping in the background, so that few people knew of him and his success and saying, “The story runs on. But there is none with more romance than that of the Georgia boy, selling newspapers on the street, who became czar of the bike game and made a fortune at it.”

…and I would have to add, that many today, still don’t know a thing about John Chapman and his impact on the sport of bicycle racing and on my hometown of Red Oak as well as Palmetto, Georgia.

Martha Stevens is my father’s aunt…he is still alive and living in Florida (90 years old)

I can remember him talking about his Aunt Martha (his father’s sister) when we were growing up.

He’s been to their house in Summit, N.J. many times as a child and describes it as “enormous”

This article was very interesting and I heard much of the information before but I had nothing to relate it to…at 90 his memory is still AMAZING!

We have a “Doll House” log cabin that was crafted by one of John Chapman’s workers…the craftsmanship and attention to detail is remarkable!

Thank you!