I love the story of the Red River Raft for several reasons.

It has an intriguing name. You might see in your mind’s eye images of pioneers racing down a river with all their earthly possessions stacked on a hastily fashioned wooden log raft, but that’s not what this story is about.

In fact, the story involves the inability to move on a river.

Yes, this story is not what you expect, and if you spend any time around here then you know I like the unexpected change-up in content.

This story also embraces a bit of historical myth, which again, if you spend any time around here reading my meager little offerings you know I like to bust those myths as much as possible, but in this case, it might be okay to include the myth with the lesson content as a hook to draw students in or in my present situation to interest the reader.

This story also has geological and geographical implications and a bit of science. It spans several historical eras including Native Americans, pioneers, and the transportation age, and some interesting characters as well.

Although it was called the great raft it was in fact a gigantic log jam – a huge “raft” that clogged the Red River and ran for 160 miles. The “raft” was formed over thousands of years as the flood waters of the Mississippi River would engulf the smaller Red River forcing large amounts of driftwood upstream. The result was a tremendous log jam comprised of cedar, cypress, and petrified wood.

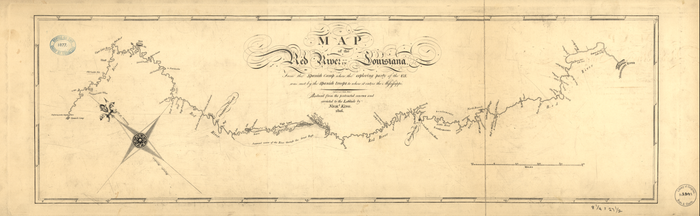

In 1806, President Thomas Jefferson assigned Thomas Freeman and Peter Custis to explore the southern Louisiana Territory. President Jefferson ranked their trip second only to the more well-known Lewis and Clark Expedition. Freeman and Custis discovered the log jam north of present-day Natchitoches, Louisiana and described it as “so tightly bound a man could walk over it in any direction.” It covered the width of the river and went to the bottom.

See the map of the expedition below:

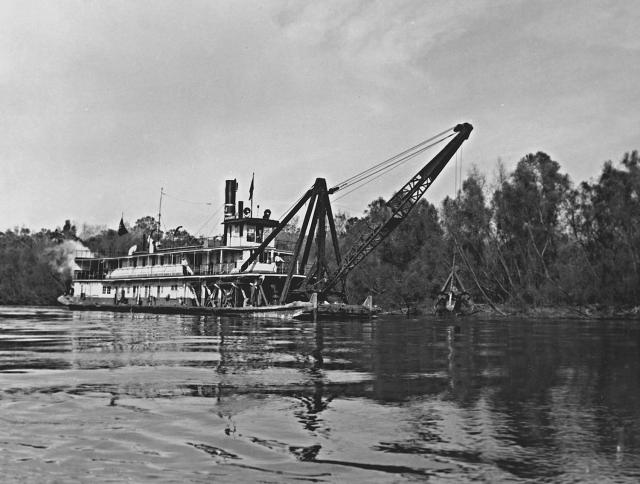

The first effort to clear the river came in 1833 when Captain Henry Miller Shreve (1785-1851) of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and namesake for Shreveport, Louisiana, used an invention Shreve had contrived called the “snag steamboat” to pull the logs out and send them floating downstream. The boats had and interesting nickname…”Uncle Sam’s Tooth Pullers”. These boats were not just used to clear the Red River Raft. They were also used to clear snags along the Mississippi and other major waterways.

It took three years to clear approximately seventy miles of the river, but by 1839, the raft had reclaimed much of what had been cleared.

One scheme after another followed for the next thirty-two years trying to free the Red River Raft. Some resources report the government spent over half a million dollars to remove the log jam.

By 1872, Lieutenant E.A. Woodruff, an Army engineer tried his hand at attacking the log jam. He used Shreve’s snag boats, but added other boats as well including boats outfitted with saws and boats with cranes to eat away at the edges of the raft.

Eventually, another tool – nitroglycerin – was utilized when the boats could not untangle the logs. What they could not untangled, they blew up.

To keep the log jam from reforming the workers dug reservoirs, dredged the main channel, and constructed dams.

By 1900, the Red River was permanently opened for trade from the Indian Territory to the Gulf of Mexico.

Now the story takes a little turn to the former port city of Jefferson, Texas, a town along the Red River described as the westernmost outpost on the river that spread out along the banks of Big Cypress Creek.

The log jam existed when the town formed, and in their case the log jam helped them. The logs made the water level rise in the Big Cypress Bayou at Jefferson and permitted commercial riverboat travel, and of course, Jefferson became a very important port in Texas between 1845 and 1872.

The town reached its peak right after the Civil War when the population rose to 7,297 people. The town’s history page states:

“The years after the Civil War became Jefferson’s heyday with people coming from the devastated southern states seeking a new life. In 1872, there were exports in the thousands of dry hides, green hides, tons of wool, pelts, bushels of seed, several thousand cattle and sheep and over a hundred thousand feet of lumber. For the same period, there were 226 arrivals of steamboats with a carrying capacity averaging 425 tons each”

Hotel registers from the early days indicate some very important folks moved through Jefferson including Ulysses S. Grant, Oscar Wilde, and Rutherford B. Hayes.

The 2020 census indicates a small population of 1,875, so, why the decline?

Enter Jason Gould (1836-1892), the railroad magnate. Mr. Gould came to town wanting to bring the Texas and Pacific Railroad through Jefferson. One version of the story goes that Jefferson’s town leaders would have nothing to do with the newfangled railroad because they were happy with the river traffic. They turned down Gould’s offer to purchase the right-of-way, and the Texas and Pacific line did not go through Jefferson.

Gould was very unhappy when the folks in Jefferson turned him down, and there is a popular story – just a story some say – that Jay Gould predicted the grass would grow in the streets of Jefferson since they turned their backs on his offer. It is said he wrote in the register of the Excelsior Hotel that the refusal to accept his offer would mean “the end of Jefferson.” There is also a story concerning the fact he gave assistance to those removing the log jam which eventually caused Jefferson’s decline as a port city.

There are those who say Mr. Gould never did such a thing mainly because he did not own the railroad until the late 1880s, and he was not in Jefferson until later either, but it does make for a good story.

Many people also point to the fact that the town attempted to build its own railroad from Shreveport to Marshall in 1860, but only forty-five miles was completed before the outbreak of the Civil War. Folks argue the town couldn’t have been against the railroad since this attempt was made.

Most amazingly considering how they protest the story isn’t true, the city of Jefferson capitalizes on the story. It seems they have Jay Gould’s personal rail car, The Atalanta, on display and own it outright.

Leave a Reply