Take a good look at the photo I have placed below. The time according to the archival notes with the photo is the 1940s. It appears to be a rainy day in Atlanta as cars and a trolley bus travel on Pryor Street. The large brick building looming in the right upper corner is the Kimball House Hotel which took up an entire city block at the south-southeast corner of Five Points, bounded by Whitehall Street (now part of Peachtree Street), Decatur, Pryor, and Wall Streets. It opened on New Year’s Day in 1885, and by 1959 had been demolished for a parking lot.

The multi-storied building on the left side of Pryor is the Thornton Building named for Albert E. Thornton (1885-1953), grandson of Atlanta pioneer Alfred Austell who had his own set of buildings located on that section of Pryor in the 1870s. The Thornton Building, built between 1931 and 1932, is still standing and today is known as 10 Park Place. The building is unique in that it is one of the last commercial buildings erected in the city before the slow down caused by the Great Depression. Another unique point regarding the building is that it has movable walls making it easy to reconfigure office space for tenants.

Across the street from the Thornton Building, you can see the neon sign advertising Shorty’s Steak House which first opened at 15 Pryor Street, S.W. in 1937.

Here is another view of the location taken in 1952 from the middle of Pryor Street.

I have always been drawn to this image due to the wet streets and glow of the neon sign. I imagined a long counter with stools, a couple of middle-aged waitresses with starched which aprons who had seen better days, and a fat bald cook in food-stained pants and a white t-shirt with a pack of Pall Malls rolled up into one of his sleeves. This would be the Shorty of Shorty’s Steak House – a man that had received his name due to a long career as a short order cook following a stint as an Army cook where he learned his trade.

Once I decided to do a little research on Shorty’s Steak House, I discovered I had been incorrect in my assumptions regarding the restaurant’s namesake because while I never discovered the exact reason why he was called Shorty, Joseph “Shorty” Werner never served in the U.S. Army. In fact, he was a Russian immigrant who came to Atlanta in 1913 when he was just fifteen years old.

Shorty first found employment at Silverman’s Restaurant in the Candler Building and later Harvey’s Restaurant at Five Points where he worked as a greeter, what we would think of today as a host greeting people as they entered the restaurant and showing them to their tables. It was at Harvey’s where Shorty met Pete Coronis, a Greek immigrant who first arrived in the United States on March 1, 1906 and was tagged for Atlanta, Georgia. Though Shorty had a thick Russian accent and Coronis tripped over his vowels when he was excited even into the late 1950s, the two men understood each other completely and made fast friends. When Shorty decided to make a go of it with his own place, Coronis joined him as cook.

They opened Shorty’s Steak House on Pryor Street in 1937 with three booths, three tables, and a tin-stool counter when one meat one meat, two vegetables, bread, drink, and dessert cost thirty-five cents.

The restaurant began serving breakfast at 6 a.m., lunch, and dinner every evening until 8:30 p.m. every day but Sunday to businessmen, lawyers, travelers who might wander down Pryor Street from the Kimball House, and many others. Coronis would arrive at work as early as 4 a.m. each morning to personally select every leaf of green or choice cut of meat. The result made Shorty’s Steak House famous among those who wanted a steak just so.

In those early days Shorty’s Steak House advertised with the tagline “A good place to eat.”

This picture of Coronis appeared in The Atlanta Journal in Morris McLemore’s Town Talk column in December 1947.

The purpose of the column was to compare Coronis with the movie star, Sidney Greenstreet I have pictured below. McLemore explained, “Shorty’s Steak House on Pryor Street has a unique dish – French fries with chills…crisp slivers of potato are a specialty, but the chills are thrown in for free. They come to the customer, usually in mid-pitch from plate to mouth, when the unwary eater is at eye level with the opening between the dining room and kitchen. At this angle he stares straight into the eyes of a man who looks exactly like Sidney Greenstreet.

The shock is terrific. The eater gets the feel of a knife at his throat and a mellifluous voice intoning deadly comments about shortening of breath.

Mr. Greenstreet is a distinguished Hollywood actor, with emphasis being placed upon his ability to get the last shred of terror from sly remarks as “The Falcon” or some other arsenic artist. You may remember him as Clark Gable’s repulsive boss in “The Hucksters.” [He also starred in the 1942 movie Casablanca.]

His Atlanta counterpart is one of the better kitchen foremen in these parts, Pete Cronis, who does nothing more vicious than whack at a side of beef with a meat cleaver…

…For forty-one years, [Pete Coronis] has called Atlanta home – he remembers when horses were watered at Five Points and later when the Piedmont Hotel boasted a rim of chairs around the lobby which faced out on the intersection of Forsyth and Luckie and was the rendezvous are for local gentry…”

Looking through old newspapers it appears like many establishments Shorty was constantly advertising for waitresses, but he did have some who stuck around for many years. Lois Garrison Stowe, a dry witted red head, arrived at Shorty’s in 1938 from Covington and she didn’t leave until well after Shorty and Coronis had gone on to their reward in Heaven.

In the Around Town column published by Hugh Parks in The Atlanta Journal in March 1963 a picture of Lois was painted for us and Parks marveled that it was astounding Shorty’s Steak House had one waitress who had been waiting on the trade there for twenty-five years.

From the column Waitress Stowe said, “Shorty…hasn’t changed a bit [since I began working for him, he’s] lost a couple of teeth. He was just as bald then as he is now, but I’ve told him you can’t have brains and hair, too.”

Mrs. Stowe briskly hand brushed her clean white uniform, “I weighed eighty-six pounds when I went to work for Shorty,” she said. “Now I weigh one hundred and sixty.” She looked up and smiled. We smiled back.

The column continues, One day a gentleman on the string-meat side informed her she had a wonderful personality and then, having softened her up, he thought, felt free to ask why she didn’t lose a little weight.

“Well, one thing about it,” replied Mrs. Stowe companionably in a voice that carried in the mezzanine, “they don’t have to shake the sheets to find me.” When he went out the door his head was bent so low that people thought he was looking for a dime.

Another customer told Mrs. Stowe she was so cheerful he didn’t believe she’d ever had a bad day, but she has had her share, she just hasn’t let them show very much. She lost her husband, Hoyt, a wounded World War I veteran, [in 1958.] He died of leukemia after lingering in a hospital for two years.

While he was sick, Mrs. Stowe, the mother of two girls, held down two jobs. She worked at Shorty’s until 8 p.m. and then hurried to Emory where she served as night supervisor of the cafeteria until 1 a.m. “I’ll tell you it was some rough going,” she confessed.

Why has she remained at the same restaurant so long? “Well, we’ve had the same customers for years,” she said, “and then Shorty – I think he has put shoes on every little white and colored child that has come up Decatur Street barefoot. He grabs them by the hand and takes them across the street to George Pierce’s.”

[She continued,] “I truly like the public – it gets in your blood.

During my research I also discovered that Shorty not only bought shoes for many Atlanta children who needed them through the years, he also gave away hundreds of meals to people who had no money but needed to eat.

Another waitress at Shorty’s Steak House known for good deeds was Gladys Morgan. She was well known in the 1940s for adopting an orphan each year to provide Santa Claus for the child. In 1948, Shorty’s was one of the collection points for the Grace Purcell fund. Grace was a five-year-old girl from Lovejoy who had no arms. Several Atlanta restaurants were collection points for the fund to purchase artificial arms for Grace, but Gladys Morgan was the person overall in charge of the fund at Shorty’s.

Waitress Stowe was a bit more calculating about her gifts of charity as Park’s column described, “One morning Mrs. Stowe had a bum walk in and say, “Lady, will you give me a dime so I can get a cup of coffee up the street?” For a rare once she was speechless. She silently set a Shorty cup of coffee before him instead.

On another occasion, she was affected by a stranger’s tale of hardship that she took up a collection among the other waitresses and raised six dollars. She was strolling up the street a trifle later when she looked in a grill and there was her pal playing the pinball machine. Mrs. Stowe may be kindly, but she is not stupid, and she marched in and made him give her their money back, what was left, which was about four dollars.

Through the years I’m sure Shorty’s Steak House had its fair share of Atlanta’s movers and shakers sitting in a booth or taking a stool at the counter. Two that I know about were Herman Talmadge who it was said always visited Shorty’s on his way into town from Lovejoy to order a plate of short ribs before moving on to more important business.

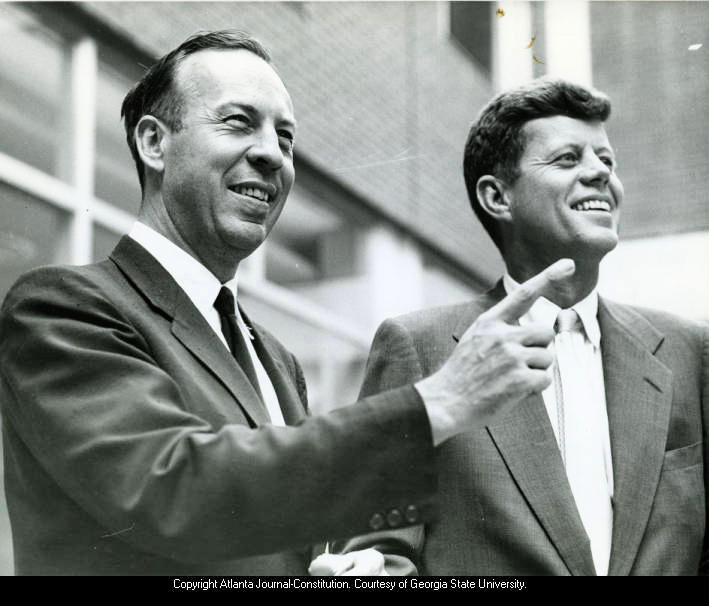

Another regular was the attorney Robert B. Troutman, Jr. a member of the law firm Spalding, Sibley, Troutman, and Brock which today is King and Spalding. Troutman who roomed with Joseph Kennedy, Jr. at Harvard and during the 1960 Presidential campaign he served as the manager of John F. Kennedy’s Southern campaign, would arrive a little after 5 a.m. each morning while Coronis was setting up for the day saying he could get more work done by coming in to eat a bite early before the rush ordering one scrambled egg and piece of tenderloin steak for his morning fare.

Troutman was known to double-back to Shorty’s for lunch, too. In 1951, he began to kid around with the waitresses by walking in several days in a row and announcing he was in the mood for some chitlins knowing good and well they were not on the menu. A few times he jazzed up his chitlin request by asking for a side of turnip greens, too. One day, after several requests for chitlins had been received, Shorty went out and purchased some and boiled them. When Troutman came in and remarked to the waitress, “I reckon I’ll just have a nice mess of chitlins,” the waitress returned with a platter heaped with ten pounds of odiferous, unadorned, and cold white chitlins. A friend later remarked that Troutman laughed so much he couldn’t eat them.

I don’t know about you, but an overdose of laughing would not be my reason for choosing not to eat chitlins.

When a new Fulton Federal Saving and Loan was built at Edgewood Avenue, Pryor, and Decatur Streets in 1955, Shorty’s Steak House moved around the corner to 16 Decatur Street at Five Points. They occupied one of the store fronts in the Olympia Building’s Decatur Street side. New Ads were placed in the paper telling patrons “Meet your friends at Shorty’s.”

The Olympia Building was constructed between 1935 and 1936 and made famous with the installation of the Coca Cola neon sign and Wormser Hats. The building forms the southern boundary of Central City Park and is defined by the intersections of Edgewood Avenue, Decatur, and Peachtree Streets.

Going back to before World War II, Shorty’s Steak House had been the site of an annual dinner gathering for Georgia Tech’s Junior Varsity football team given by Mercer McCall “Mack” Tharpe, former all Southern tackle in 1926 at Georgia Tech and later line coach in 1934. November 1955 was no different except the dinner was hosted by Mack Tharpe’s brother, Bob, and his brother-in-law, J.L. Brooks, a former Georgia Tech guard, since Mack, a Navy pilot during World War II, was tragically killed in action in February 1945. Shorty always encouraged the Tech players to eat as much as they wanted during the multicourse meal.

The end of Shorty’s Steak House long run began with the death of Pete Coronis in May 1963 followed by Shorty’s death six months later. When he realized the end was near, Shorty sold the restaurant to longtime waitress, Lois Garrison Stowe. It is uncertain at this point how long she was able to keep the doors open, but a 1970 newspaper mention stated Mrs. Jo Robinson was running the place. Lois Garrison Stowe died in January 1994. Her obit states she was a retired cashier and former owner of Shorty’s Restaurant.

In 1979, Shorty’s location became the first home for Harold’s Sandwich shop owned by Harold and Goldie Weinstein. It’s interesting to note that Harold’s Sandwich Shop later moved to Forsyth Street where it remained for many years until Harold died in 1990. Two years later, his son, Steven, opened Harold’s Uptown Deli at Capital City Plaza across Peachtree Street from the Atlanta Financial Center.

Leave a Reply