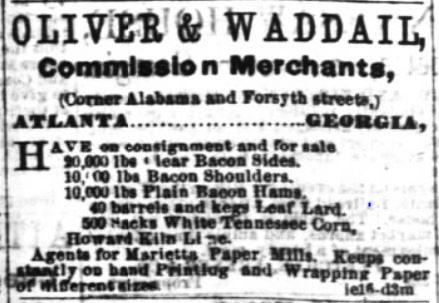

On October 21, 1883 The Atlanta Constitution reported a force of fifty men were engaged in excavating the old Oliver corner for what would be the new Constitution building. The old Oliver corner was the southeast corner of Alabama and Forsyth which had been the location of J.S. Oliver’s commission warehouse dating back to 1868 when John S. Oliver (1822-1895) partnered with B.C. Waddail.

By 1870, J.S. Oliver had sole control of the business, and by 1875, he was a cotton commission merchant. By 1881, the company had failed due to poor health aggravated by Oliver’s broken heart after the loss of his wife in 1878.

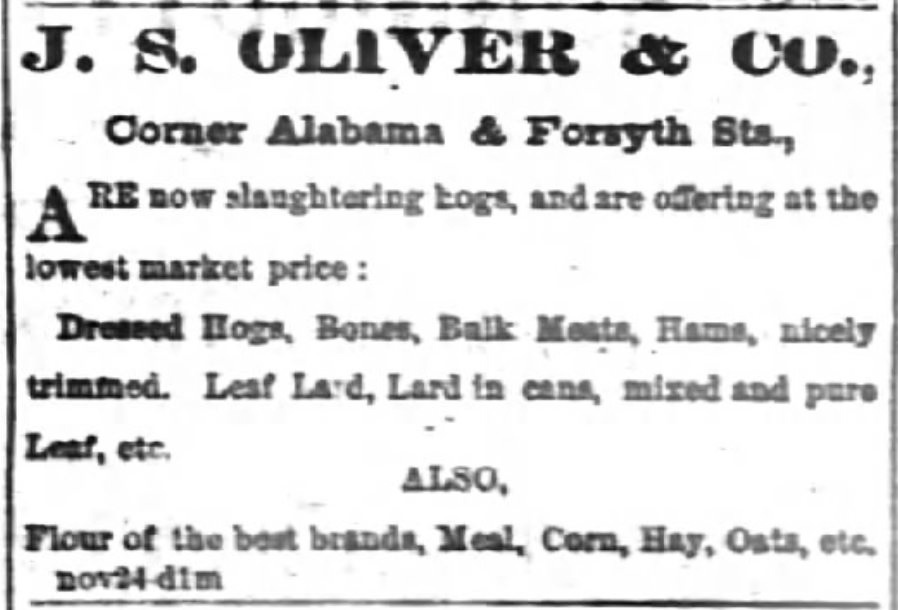

The former Constitution building located on Broad Street was sold at public outcry on Wednesday, May 7, 1884 at noon. The hope was the money realized from the sale could be reinvested in the new building that was under construction at Alabama and Forsyth corner. The Constitution building on Broad was five stories high and advertisements stated it was “built in the best style of brick with handsome finish and massive and attractive front located on one of the busiest and best streets in the city adjacent to the bridge that connects the two sections of the city…”

By July 11, 1884, the newspapers were full of advertisements seeking tenants for the offices and rooms in the new building that weren’t being utilized by the newspaper. The building boasted heat and electric light with each room, and what was described as an “elegant” Otis passenger elevator that would run constantly because the major tenant in the building, the newspaper, never slept. This initial elevator was operated with pullies. A newer model would replace it in 1912. You can read a poem written about the elevator by a newspaper employee Louis “Press” Preston Huddleston here at my post Ode to an Elevator.

The new building costs a total of $100,000, and it was a skyscraper by Atlanta standards in the mid-1880s. Great views of the booming city could be obtained from the top floors. Not only did the building boast every modern convenience at that time, but some sources state also one of the first typewriters in the city was located there as well.

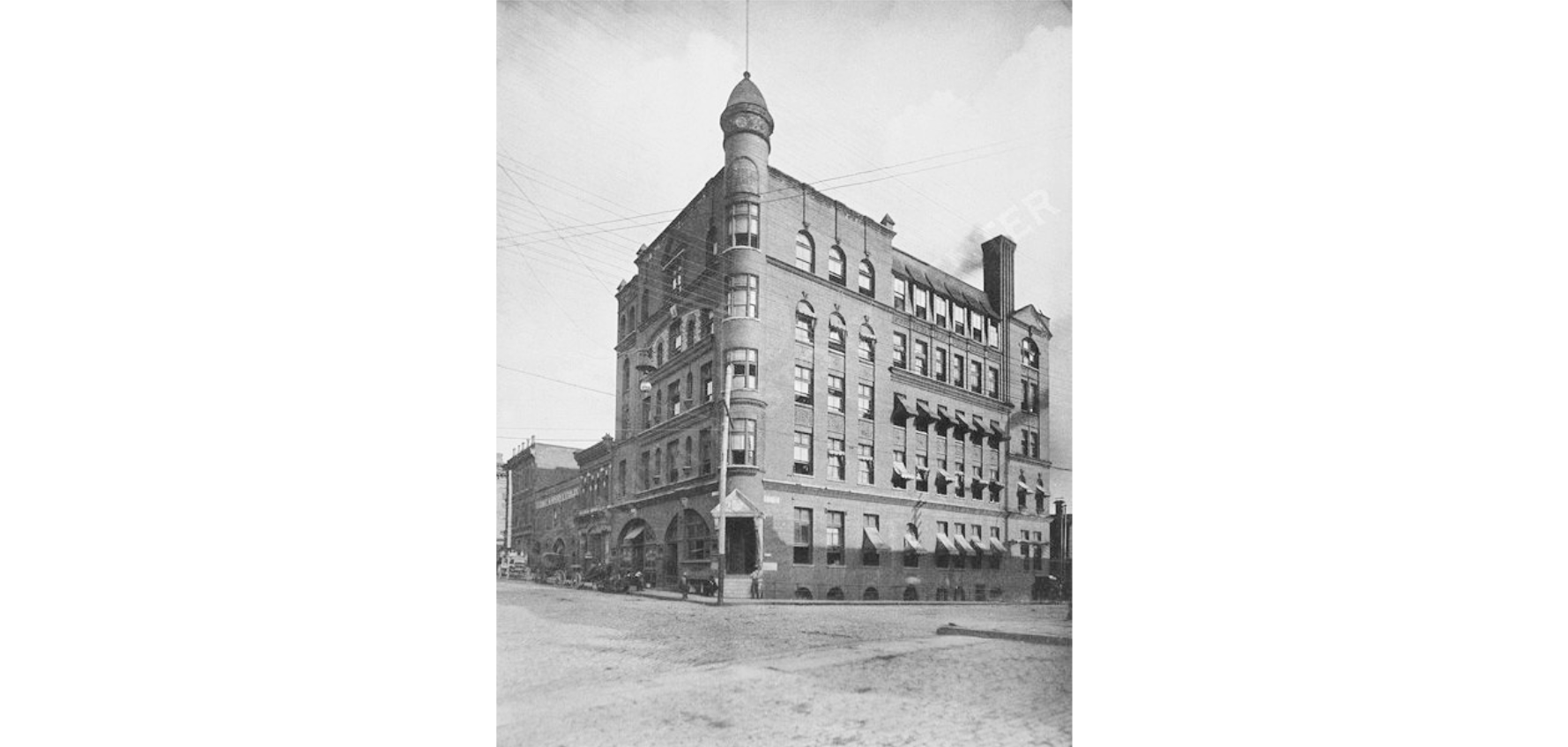

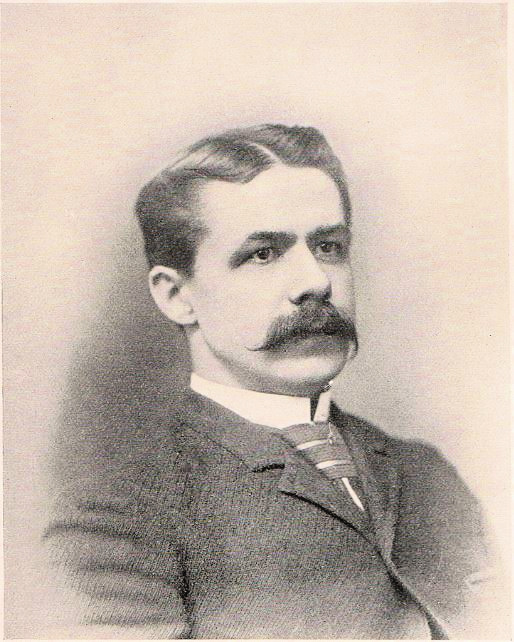

This was the building with the last physical links to those rugged giants of journalism, Evan Park Howell (1839-1905) and Henry W. Grady, per Bem Price, staff writer for the Associated Press would write in 1947. Price went on to say it was Howell who was responsible for “the greatest single foundation in The Atlanta Constitution’s history” regarding his “dictum that a newspaper ought to have writers, and he got them.

Howell would serve as Atlanta’s mayor between 1903 and 1905 and served on the city council a few times. While editor at the Constitution in 1895, he sent out transcripts of Booker T. Washington’s “Separate as the Fingers” speech given at the Atlanta Exposition across the country.

It was Howell who brought in some of the early greats including Henry W. Grady and Joel Chandler Harris, and he understood it was necessary to bring in others who were well known and had large followings such Bill Arp aka Charles Henry Smith. Howell also realized “writers on the editorial pages ought to be free, within the limits of reason and good taste,” and that foundation has remained through the years.

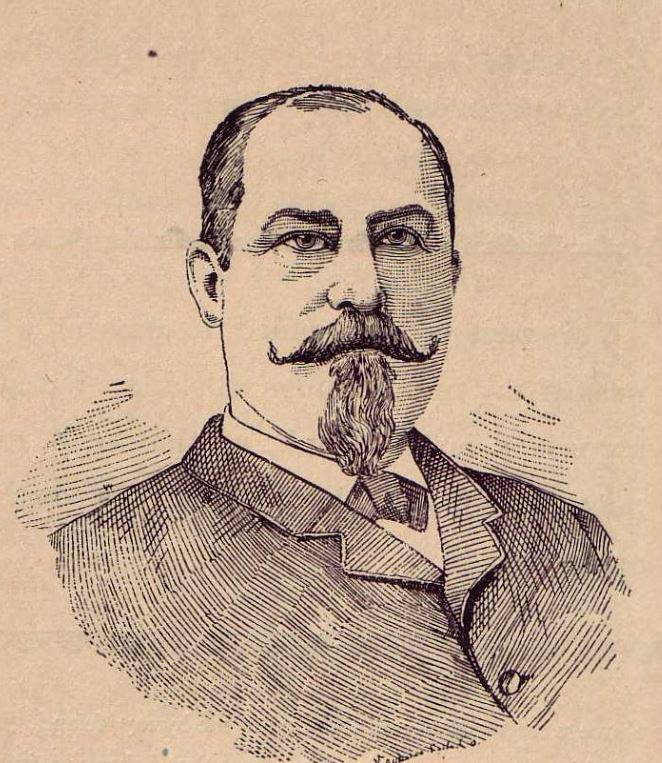

Following a stint with the New York Herald, Henry W. Grady accepted a reporter-editor position with The Atlanta Constitution. In 1880, he borrowed $20,000 to purchase a one-fourth interest in the paper. During his nine-year association with the Constitution, the paper quickly grew into one of the most influential in the state. Bem Price wrote of Henry W. Grady describing him as “…the man who started the fight for a New South to wipe out the animosities between North and South left by the War Between the States and left his mark on a generation of journalists as few men ever have.”

This was the building where a miniature brass cannon was used to notify the city when anything important occurred. Henry W. Grady had the cannon made in anticipation of Grover Cleveland winning the White House in 1884,the first Democrat to do so since the Civil War, and Grady was able to fire it for the jubilant crowds gathered to celebrate. The cannon was fired again by fellow editor Ralph McGill when John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960. Below is an image of Editor, Gene Patterson, Ralph McGill, and others with the cannon in 1960.

This is the building where at 9 p.m. on August 31, 1886, the Charleston Earthquake not only made news it was also felt. The Constitution reported on the morning of September 1, 1886, “…At five minutes before nine there was a little tremor of the floor [in the Constitution building] like unto the movement created by a dog trotting across. Quickly that changed to a shaking such as a wagon produces in crossing a bridge. A second or so more and the great structure shook convulsively, and began rocking and trembling, the movement being from east to west and west to east…You cannot imagine the situation if you have never there. Every man in the building expected the house to fall to the ground within a minute. A reporter’s desk turned half over. The boys fled toward the elevator. The printers rushed pell-mell down the back stairs…The elevator man remained at his post, and [said] he did not feel the shock at all owing to the constant motion of the elevator…”

This is the building where Grady and Howell often disagreed, but they acted like gentlemen and still managed to publish the paper and remain friends. They were often on opposing sides including the prohibition question in 1887. Howell was a bourbon man and Grady was pro prohibition. The two divided the editorial space and reprinted editorials from other newspapers giving both viewpoints.

This is the building that had fireplaces on each floor that were used for many years. A few days before the move to the new building a fire broke out from one of the broken wires where a press machine had been removed. Smoke boiled up, filling the building. A young reporter on the third floor heard that an order had been given to vacate the building. He dashed up to the fourth-floor copy room to get his coat and hat. The steps and elevator had been crowded, but, on the fourth floor sat the veterans of a thousand such alarms. They went right along, typing and editing, and, of course, in due time the fire was out, with no real damage.

This is the building where the artist Norman Rockwell wanted to immortalize the infamous Constitution copy desk for one of those famous Saturday Evening Post magazine covers, he made so famous from 1916 to 1962, but unfortunately, that never materialized. By the time the newspaper moved to the opposite street corner in 1947, the copy desk had become well known for its eccentric irreverence, so it’s rather sad it can’t live on in one of Rockwell’s paintings, but there are stories that survive.

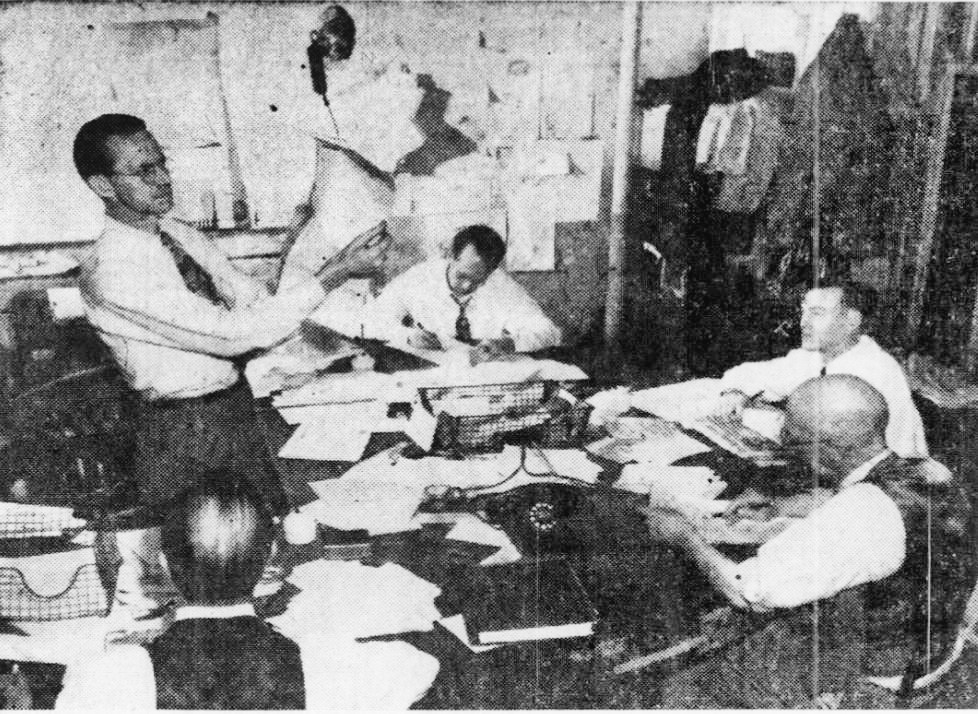

This is the building where the newsroom on the fourth floor assumed a colorful personality of its own. Various words have been used to describe the Constitution’s newsroom between the late 1880s and 1947. Unregimented, free and easy, and an irreverent atmosphere are just some of the descriptors I found. There on the fourth floor in one corner you could find the horseshoe shaped copy desk where headlines and articles were edited. It was there that Telegraph Editor Joe Davis kept a scale he used to weigh stories which ran too long. He would throw them back to the reporter with the caustic order, “Cut two pounds out of this.”

From the original picture caption, “In the above picture, the bald spot just under Davis’ elbow belongs to Copy Reader Earle Watson, and the one to Watson’s right adjourns the head of “Pop” Kerby. Carl Broome is next to Kerby, and the one making like work is George Keeler. Decorations on the wall by Parker Lowell, alleged lampooning cartoonist.”

This is the building where the walls around the copy desk were filled with the penciled cartoons by artist-copy editor H. Parker Lowell (1888-1970) that were still there years later when the building was finally demolished by Rich’s. Lowell’s cartoons were often described as “biting,” and he was described as someone who never permitted pomposity to exist in the office for more than five minutes. In retirement Lowell volunteered with the Red Cross as a swimming instructor at the Downtown YMCA.

I wonder if any of his cartoons survive?

This is the building where for many years a stuffed duck hung above the copy desk. The story goes that a couple of Constitution reporters decided the American dinner table needed a new kind of poultry. One of the men telephoned a friend who worked for one of the newspapers in Los Angeles and requested an albatross which could be found off the California coast. A few days later a box arrived that contained a beat-up stuffed duck with a note saying, “Pursued by helicopter and captured by hand over Catalina.” The prized “albatross” hung over the city desk for years it is said until someone took it to an annual meeting of the Georgia Press Association in Athens where it disappeared.

This is the building where Assistant Managing Editor Lee Rogers tried to get a horse up the freight elevator for an interview, where a bust of “Old Granddad” – the famous drinking man stood over the desk of managing editor Josh P. Skinner, and a monkey’s face carved from a coconut leered towards the copy desk with a sign that said, “Don’t stare at the editor. You may be crazy yourself one day.” The men’s washroom at one point had an envelope pasted on it that contained a razor blade and a note that read, “Do not remove, for wrist slashing only.”

This is the building where Managing Editor Skinner gave then Cub Reporter Bob Lewin a famous lesson in the art of interviewing someone famous. Skinner advised, “Keep your pencil poised, but don’t write a damn thing. He’ll keep waiting for you to write. After a while he’ll get nervous and ask you if you ever take notes. Then tell him he hasn’t said anything worth printing and he’ll break down [and finally give you something worth printing].”

This is the building where Frank Lebby Stanton (1857-1927), an early columnist and Georgia’s first poet laureate, would take Louis Gregg’s pet gopher each Saturday and pawn it for a quarter. Gregg, a staff cartoonist, would visit the pawn shop each Monday on his way to the office to retrieve what I am assuming was a stuffed gopher, but through the years Gregg kept at least one live animal in the city room. It was a terrapin and was his cartoon mascot named Gilly. One night Stanton and a friend of his were drinking bourbon in the city room and they suddenly noticed the friend’s tall silk hat which he had placed on the floor was walking out the door. Unbeknownst to the friend he had placed his hat on top of Gilly. Apparently, Stanton and the friend fled to a nearby saloon while Gilly continued down the hallway with the top hat perched on his back. It was said the sight drove several of the teetotalers on the floor to grab a drink themselves.

This is the building where Stanton was the only employee to have his paycheck personally delivered each week from the Constitution’s cashier. About three weeks into his tenure at the paper the cashier approached Mr. Howell and told him that Stanton had yet to draw a cent of his salary. When Howell made an inquiry, Stanton replied no one had offered him any money since his arrival. From that day forward Stanton’s check was hand delivered by the cashier. Stanton would rise, part his frock-coat tail, bow saying, “Thank you, Sir. This is most gracious of you.” Stanton always marveled at the miraculous good luck of being paid to do something he enjoyed doing.

We should all be that fortunate!

This is the building where Frank L. Stanton managed to save an Oklahoma man from hanging. The man’s name was Bill Jones, and though he didn’t know the man Stanton wrote a poem over the man’s plight, and the Governor of Oklahoma was so moved by it he pardoned Jones. Days later a man was seen leaving Stanton’s office with tears in his eyes. When asked who the man was, Stanton replied, “That was Bill Jones.” When further inquiry was made if it was the Bill Jones who was saved from the hangman, Stanton said, “That is the third Bill Jones that has been in this office this month to thank me.”

This is the building where the boys in the newsroom set up a box bearing the sign “Money for the Blind” to benefit News Editor Sam Cox with a pair of glasses after he had idly observed he needed them. A few years later, Cox was still without glasses, but he was known to drain ten dollars of pennies from the box every three months or so.

This is the building where Telegraph Editor Joe Davis brought an electric train, a Christmas present for his nephew, to the office. The entire staff took a holiday of sorts to play with the train while telephones jangled off their hooks and the composing room called for copy. Later, when one of the irate boss men demanded to know what was going on, a reporter explained they had all been busy working a train wreck.

This was the building that served as an incubator for many talented journalists including Jacob D. Gortatowsky (1886-1964) who eventually left the city desk to become the head man of the entire Hearst newspaper setup. Pierre Van Paasan, whose World’s Window was widely syndicated, went on to Pulitzer’s New York World and finished off as a top war correspondent before settling down in his native Holland as a preacher. Another Pulitzer winner was H. Parks Rusk, Sr. (1901-1986), brother to Dean Rusk who served as U.S. Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969.

This is the building where Joel Chandler Harris (1845-1908) worked while gathering and writing the African American trickster stories regarding the adventures of Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox told by a fictitious Uncle Remus. Harris would be hired by The Atlanta Constitution in 1876 and would remain on the paper’s staff until 1900 where he was quickly recognized as an important voice in the New South publishing his own books, novels, and children’s literature. He also founded Uncle Remus Magazine. At the time of his death, Joel Chandler Harris was remembered as “the most beloved man in America.”

This is the building where the beloved Celestine Sibley (1914-1999) began her Atlanta career in 1941. Not only was Sibley one of the most popular and long-running columnists for the Constitution, her well-written and poignant essays on Southern culture made her an icon in the South according to New Georgia Encyclopedia. During her career she also covered Georgia politics along with many high-profile court cases. Her books include both nonfiction and fiction including mystery novels. All I know is my mother always bought her books and beginning as young as sixth grade I can remember grabbing my father’s newspaper and turning to her column to read every day that it appeared.

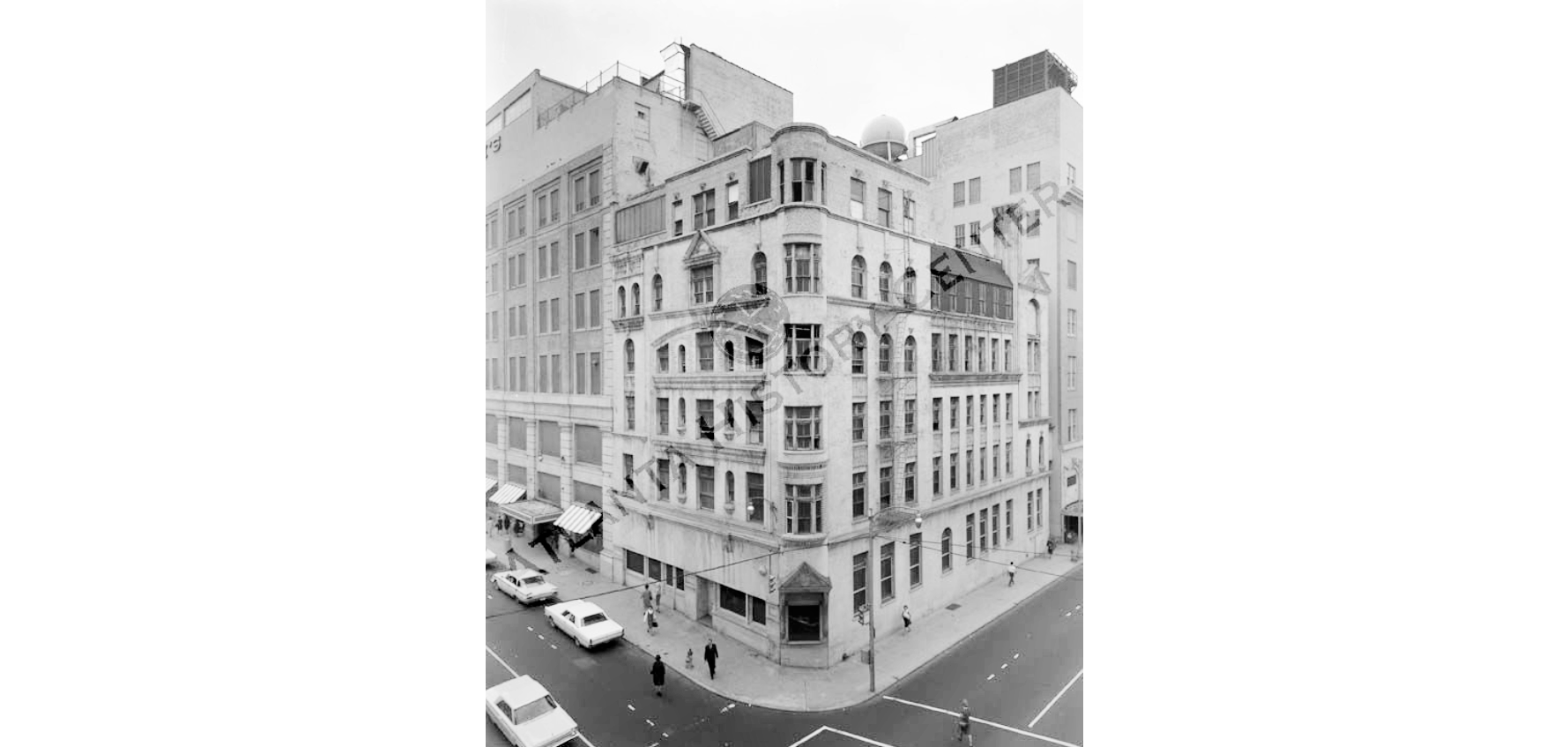

This is the building The Atlanta Constitution left behind as they moved directly across the intersection to a brand new and modern for the time building on the northwest corner of Alabama and Forsyth in late December 1947. It was a bittersweet moment for many who had worked in the older building. Though they dreaded the move from the beloved 1884 building reporters and other staff members claimed ownership of the new building when they walked from the “famed, ink-soaked old red brick (at that time) pile” and placed pennies in the still wet concrete in front of the new building. Many formed black arm bands from typewriter ribbon and placed the bands around their arms in mourning for the old building as seen in the image below.

The caption with the above photo stated, “There was mourning in the editorial room of the Constitution Saturday when an order to move over to the new building was sounded. Sorrowfully, a portion of the staff gazed for the last time at the work bench where, for years, news has been prepared for the paper’s readers. Left to right, Joe Davis, Sam Cox, Jim Furniss, Parker Lowell, Delbert Smith, Calvin Cox, John Ryan, Earl Watson, Rufus Daniel, CJ Holleran, Assistant to the Publisher, John Williamson, Mort Hayes, Stiles Martin, Bill Harrell, Kenneth Rogers, Ralph McGill, Editor; Paul Jones and Bill Boring. Note the arm bands, denoting sorrow for the group.”

At the time of the move across the intersection, Rich’s had purchased the old Constitution building and planned to use it as a warehouse. They finally demolished the building in 1967 announcing they planned to establish some type of park-like location on the corner with flowers and a bench or two.

By 1967, when the building was demolished, it was described as a “horrendously proportioned conglomeration of arches, ovals, oblongs, cylinders, verticals, and horizontals” after numerous changes through the years, but some things did remain from the old days – the capstone over the doorway was carefully removed during the demolition.

Does it survive still? Where is it?

I would love to know where it ended up.

Today the corner where the 1884 Constitution building stood is home to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Atlanta District Office, yet another one of those glass and steel structures that seem to be so prevalent these days.

Over the many years the 1884 Constitution building stood hundreds of employees from editors, reporters, and folks on the publishing line worked in the building. I’ve tried to highlight a few of them here. It would take a book of many chapters to tell the complete story and name everyone.

The 1947 Constitution building on the northwest corner still stands but has been in derelict condition for some time.

This is the building where the Constitution established their radio station – WCON-FM 98.5 as well as a television station, WCON-TV. Three years later, Cox Enterprises, owners of The Atlanta Journal, bought the Constitution and merged the two companies, although both newspapers would retain independent newsrooms for a time. Eventually, administration and sales were merged, and both the radio and television station were closed in favor of already successful ones already owned by The Atlanta Journal. It was decided to vacate the 1947 Constitution building in 1953, just six years after it had opened. The latest update to the building’s future I could find was dated July 2021. You can access it here.

Leave a Reply