As early as the Sixth century Cyrus, King of Persia, used carrier pigeons to communicate with various locations across his vast empire. Pigeons were also used during times of war to carry messages due to their homing ability as well as the speed and altitude levels they could reach.

Cher Ami, a male homing pigeon, was one such military messenger. He completed his military service during World War I after being donated by the pigeon fanciers of Britain to the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Cher Ami’s name translates to “Dear Friend,” and he proved to be just that, a dear friend to the men of the United States Army’s 77th Infantry Division.

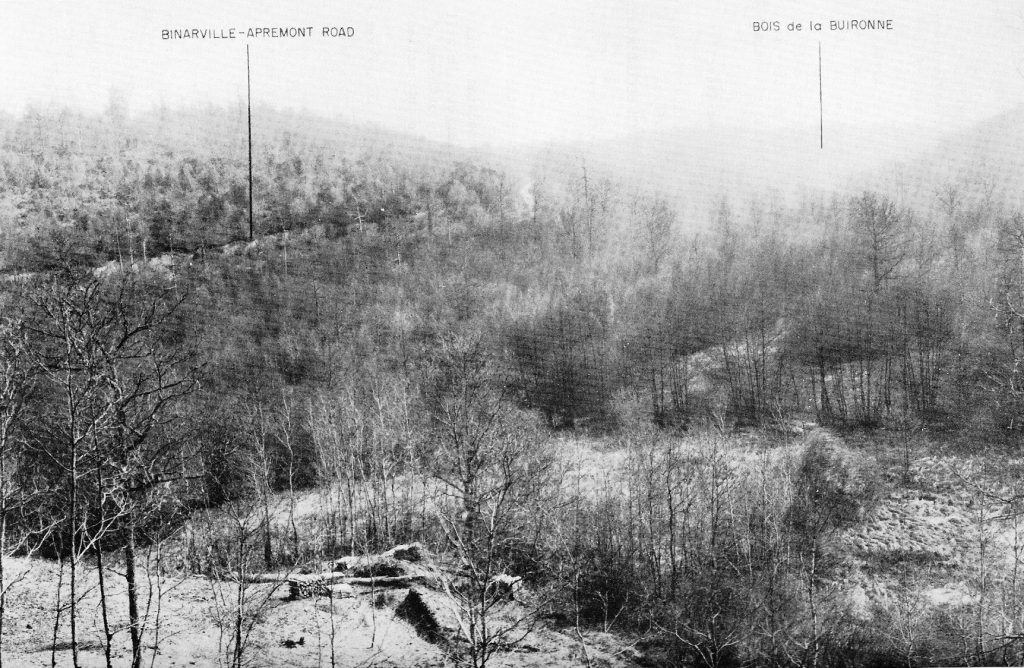

By early October 1918, U.S. troops were fully committed in some of the worst battlegrounds of France and Belgium. During the Meuse-Argonne offensive the Argonne Forest was heavily fortified by the Germans. A headstrong Allied offensive left the 77th Division trapped behind the lines near Charlevaux in an area referred to as “the pocket.” Most of the 550 members of the 77th Division were in a heavily wooded ravine surrounded by German sharpshooters and under constant fire from grenades, trench mortars, and flamethrowers.

World War I history remembers these brave men surrounded in the pocket for six hellish days as the Lost Battalion.

The 77th Division was made up of nine companies of men who were mostly from New York City. They were known as the “liberty” division due to the patch they wore displaying the Statue of Liberty. They were also referred to as the Metropolitan division due to the make-up of the group. Most of these men were recent immigrants or members of the poor working class from the streets of New York City.

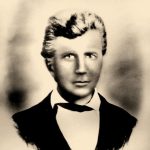

The leader of the men stuck in “the pocket” was Charles W. Whittlesey (1884-1921), a New York lawyer who entered the war in May 1917 as a captain and was promoted to the rank of major four months later.

The Germans created nightmare conditions for the men stuck in the ravine. They were under constant fire, they had no blankets, and little in the way of first-aid equipment. Food and ammunition ran low. The only water source was a nearby stream, but it could only be reached by a belly crawl accompanied by prayers that a drink of water could be had without the loss of life.

There were a few attempts to resupply the stranded men, but the needed items either fell into German hands or were dropped too far for the Americans to reach them.

Whittlesey soon realized the only way to save his men was to get a message to headquarters providing their exact location and information with the enemy’s location and strength hoping they would send reinforcements. He could either send a soldier with the hope that the man would be able to evade the sharpshooters or to send one of the division’s trained pigeons with the message strapped to its leg.

Whittlesey opted for pigeon power sending first one and then another. The birds were barely airborne when they were shot down by German sharpshooters. On October 4th inaccurate coordinates resulted in friendly fire being rained down on the division’s location in the ravine. Historians differ on how this occurred some saying Whittlesey provided incorrect coordinates. Now the men stranded in the ravine were not only suffering constant fire power from the enemy, they were also receiving a barrage of friendly fire.

On October 7th, the Germans decided the time was right to ask Whittlesey and his men to surrender honorably. They sent out a blindfolded eighteen-year-old prisoner carrying a white flag and the following message, “The suffering of your wounded men can be heard over here in German lines, and we are appealing to your humane sentiments to stop….please treat (the messenger) as an honorable man. He is quite a soldier. We envy you.”

Though there are some reports that Whittlesey immediately responded, “You go to hell!”, but he wrote in his official report, “No reply to the demand to surrender seemed necessary.” He did order that the white sheets that had been gathered up to place as signals for Allied aircraft to drop supplies be removed so the Germans would not mistake them as symbols of surrender.

Whittlesey did make one last effort to send a message to headquarters. The signal corps had one remaining pigeon, Cher Ami. Whittlesey wrote a very brief message that said, “We are along the road parallel 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven’s sake, stop it.” The slip of paper was rolled tightly and slipped into the canister strapped to Cher Ami’s leg.

Cher Ami was the Lost Battalion’s last hope.

Cher Ami flew to a treetop and paused, getting his bearings. Then as he took off, clearly showing against the sky. Shots rang out from the German guns. A shell exploded directly below the bird and killed five men on the ground. A bullet tore through Cher Ami’s breast, blinded him in one eye, and left his leg carrying the important message cannister hanging by just a tendon. Stunned for a moment the brave Cher Ami remained in the air determined to complete his mission.

Barely alive, Cher Ami made it to Rampont, twenty-five miles away. It was there where members of the signal corps saw a tattered ball of feathers plunge into the pigeon coop. Cher Ami had completed his mission.

Relief was instantly sent to the Lost Battalion and the Germans retreated. Of the original 550 men only 194 walked out of the ravine with no physical wounds, but of course, the mental wounds of being stranded for days and under constant enemy barrage would remain for the remainder of their lives. Whittlesey was immediately promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the field and received the Medal of Honor for holding his position and refusing to surrender.

Medics took care of Cher Ami and when the bird was well enough to travel, he was placed on a ship for the United States. General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, showed up to see the hero off. Cher Ami lived another two years.

Today, you can see Cher Ami on display preserved at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. After arriving at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey the pigeon led a charmed life, but he would struggle due to the wounds he received during his heroic flight. Cher Ami finally succumbed to his war wounds on June 13, 1919.

Not only did Cher Ami receive the Croix de Guerre Medal with a palm Oak Leaf Cluster, he was also inducted into the Racing Pigeon Hall of Fame in 1931 and received a gold medal from the American Racing Pigeon Fanciers in recognition of his World War I service. One hundred years following his death, Cher Ami was still receiving recognition when he was one of the first to receive the Animals in War & Peace Medal of Bravery.

Since 1921, Cher Ami has been on display at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. his body preserved by taxidermist as you can see in the image above. Through the decades thousands have learned of the pigeon’s exploits including my own fifth grade students since I always included the Lost Battalion’s story in our study of World War I.

Once home, Charles W. Whittlesey tried to return to his old life as a lawyer but found himself constantly in demand for speeches, parade appearances, and other honors of all kinds. He was been through an unspeakable experience reliving parts of it every day and then asked to relive it for the public.

A friend recounted later that Whittlesey said, “Not a day goes by but I hear from some of my old outfit, usually about some sorrow or misfortune. I cannot bear it much more.”

The last personal appearance Whittlesey accepted was the burial of the remains of the Unknown Soldier in Washington, D.C. in early November 1921 where he served as one of the pallbearers. A few days later he booked passage aboard the SS Toloa for Havanna, Cuba. He had dinner with the ship’s captain the first night at sea and it would be noted later that he was in good spirits. Whittlesey later visited the ship’s smoking room for a bit before announcing at 11:15 p.m. he was retiring for the evening, but he never reached his room and was never seen again.

A search was made the next morning and finally determined Whittlesey must have jumped overboard at some point after leaving the smoking room. Foul play was not entertained because there were a few letters in his cabin addressed to his parents, brothers, and personal friends. He even left a note to the ship’s captain with directions on how to dispose of his luggage.

Whittlesey had prepared his will in New York prior to boarding the ship for Havanna which directed that the German letter demanding the surrender of the Lost Battalion should be given to his friend and fellow soldier, George McMurtry (1876-1958), who also had been stranded with him in the ravine and received the Medal of Honor.

In his eulogy at Whittlesey’s funeral, Colonel Nathan K. Averill said Whittlesey’s death “was in reality a battle casualty and that he met his end as much in the line of duty as if he had fallen by a German bullet.”

The story of the Lost Battalion and how Cher Ami saved it remains one of the most talked about events during World War I.

Leave a Reply