Joseph Forsyth Johnson was destined to become a landscape architect because it ran in the family. His maternal grandfather was a florist while his great-grandfather, William Forsyth (1737-1804) was a botanist who was appointed superintendent of the royal gardens at Kensington and St. James Palace in 1784 and was a founding member of the Royal Horticultural Society.

Joseph Forsyth Johnson had a business card he liked to hand out that was literally filled with his landscaping exploits including fifteen different botanical and horticultural enterprises in Belfast, London, Manchester, Amsterdam, Paris, Brussels, Ghent, and St. Petersburg including “gardener” for the Queen of England as curator at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Belfast as well as the conservatories for the King of Siam. Johnson’s first book, The Natural Principle of Landscape Gardening: Or the Adornment of Land for Perpetual Beauty was published in 1874. Around 1883 he advertised “competent gardeners and workmen sent to all parts” from his landscape gardening shop that was located at 90 Bond Street in London.

In 1885 Johnson traveled to Brooklyn, New York with his pregnant mistress, Frances Clarke and within a year had accepted a position as superintendent of horticulture and arboriculture from the city. He had left behind his wife, Elizabeth Trowsdale Johnson and their six children. They knew nothing of Johnson’s mistress.

At that time Brooklyn was still a city and not a borough of New York City as it is today. Johnson arrived in the middle of a political upheaval as the parks department had been overhauled with a one-man show being “upgraded” to a five-man team costing citizens two thousand dollars more per year. Add in the fact Johnson was a bit of a pompous foreigner with a proposal to cut several trees at Prospect Park, and tensions were high.

By September 1886 Johnson was taking space in the local paper to explain why the tree removal was necessary. He was going to remove dead and crowded trees, so that others might live. His explanation fell on deaf ears. Folks didn’t like a foreigner in his position, didn’t like his stance on trees, or the fact that he was a friend of one of the commissioners. By December 1886 Johnson had been let go, but the actual reason had to do with a legal issue. It seems the Brooklyn city charter had a provision regarding hiring a non-citizen.

Joseph Forsyth Johnson didn’t return to Great Britain, however. He remained in the United States and began to look for other positions. The fact that he had a second family in the United States might have been the reason. His mistress, Frances Clarke, had given birth to their child in 1886 and over the next few years would have two more children in 1887 and in 1891.

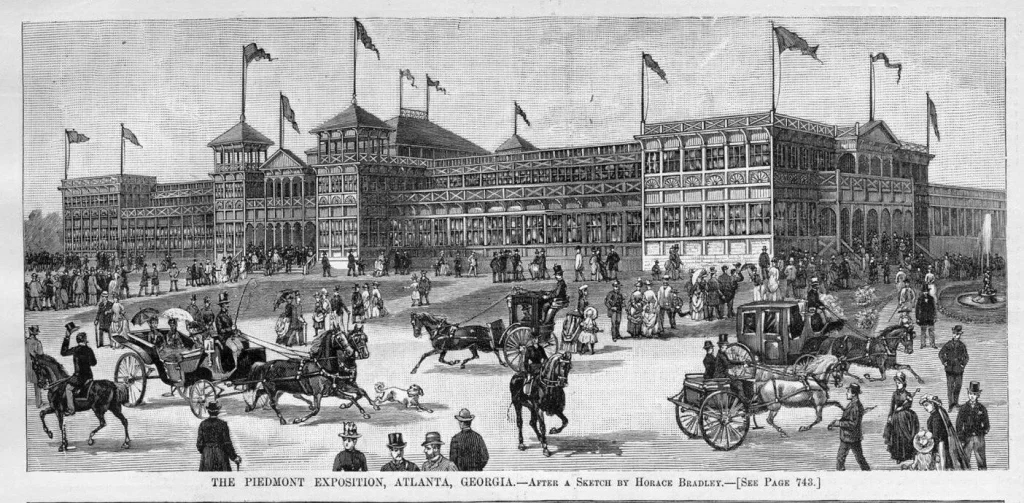

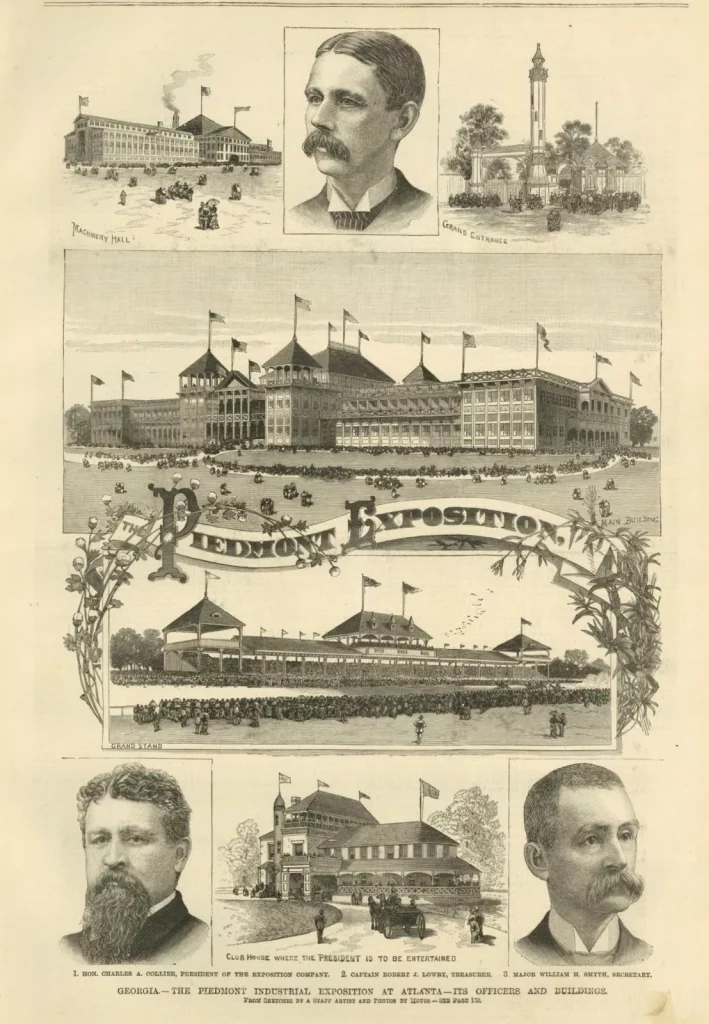

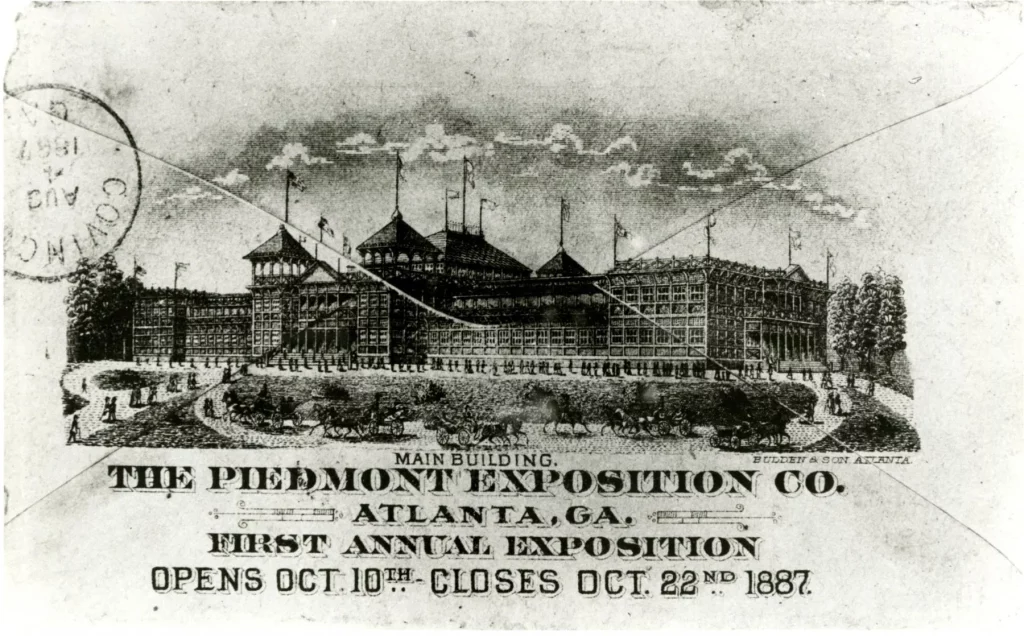

Johnson’s next major project was in Atlanta as the landscape designer for the Piedmont Exposition Company’s project involving land that was owned by the Gentlemen’s Driving Club later renamed the Piedmont Driving Club. The Piedmont Exposition Company was headed by Charles A. Collier as president, Henry W. Grady as vice president, Robert J. Lowry as Treasurer, and Major W.H. Smith as Secretary. They had persuaded the members of the driving club to allow them to use their land for fairs and expositions. The first planned exposition would be the Piedmont Exposition to be held in October 1887 and would showcase the prosperity of the region that had occurred since Reconstruction. It would also be a test to see if Atlanta could hold major regional events.

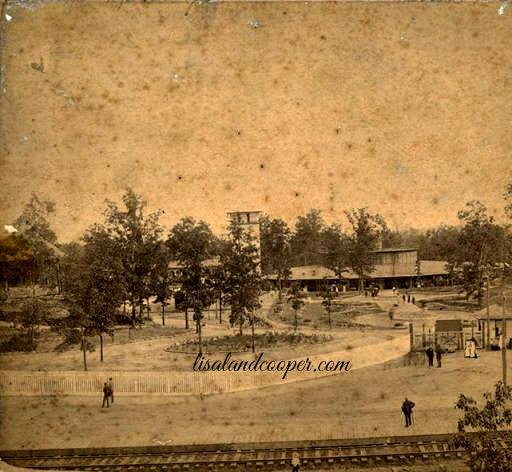

The parcel of land was outside the hustle and bustle of the city, and Piedmont Driving Club members used it for a bit of horse racing and to show off their rigs. The previous owner of the property had been Benjamin Walker who used the property as his get-away farm. He had inherited the land from his parents, Samuel and Sarah Walker who had purchased the land from Elija Pattey in September 1834 (Deed Book 226, page 309b). Pattey had been the original land lottery (1821) recipient of the property.

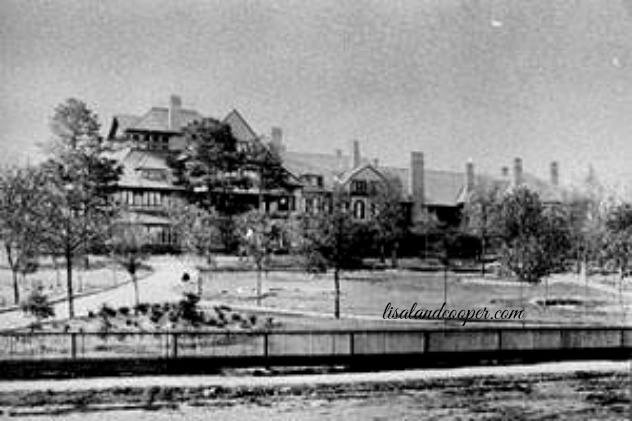

By the first of May 1887 Johnson had secured a job in Atlanta working for the Piedmont Exposition Company as the landscape engineer and soon after The Atlanta Constitution stated Johnson would arrive in the city any day and would “make plans for beautifying the Piedmont Park”, the new name the Piedmont Driving Club had given to the property. A 200-acre forest had to be cleared to make way for buildings, terraces, walkways, flower beds, and buildings. It was all hands-on deck as the public was asked to donate cannas, coleus, and scarlet geraniums. A main building, grandstands, and a clubhouse, all designed by Atlanta architect, Gottfried L. Norrman (1848-1909), had to be built as well.

Part of Johnson’s plan for land included a pond that was created from a small spring that flowed near today’s visitor’s center at Piedmont Park. In 1895, this pond Joseph Forsyth Johnson would create was enlarged, and we know it today as Clara Meer.

Work for the Piedmont Exposition was done in just 104 days!

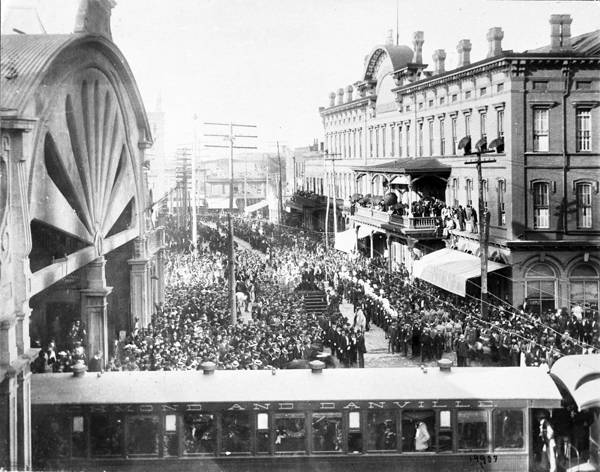

The Piedmont Exposition was a great success. It is estimated that at least 50,000 people attended the Exposition to hear President Grover Cleveland speech. The photo below shows President Cleveland’s arrival in Atlanta for the Piedmont Exposition. You can see Loyd Avenue, present-day Central Avenue, from the railroad tracks showing the crowd waiting to greet President Cleveland at the Union Depot car shed (left). The crowd is waiting for him to exit his car for a short speech at the Markham House hotel before traveling to the exposition grounds, present-day Piedmont Park.

The photo below shows President Grover Cleveland walking past the Georgia building at the Piedmont Exposition.

The Piedmont Exposition was a great success. The proceeds were used by the Piedmont Exposition Company to purchase much of the site from the driving club and funded various events they held through 1894. The city of Atlanta proved it could host major events, expositions, and fairs which led to the much larger Cotton States and International Exposition seven years later in 1895.

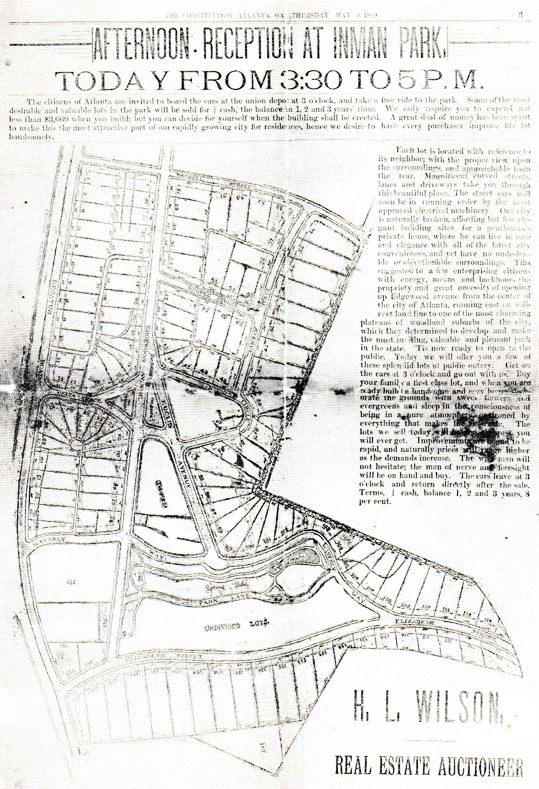

While he was working on the Piedmont Exposition project, Johnson was also working with developer Joel Hurt (1850-1926) and his East Atlanta Land Company as the landscape architect for Inman Park, the first streetcar suburb in the city. Johnson’s retainer was four hundred dollars per month plus expenses. Johnson and Hurt would work together laying out the parks and streets, an operation that included planting more than 700 trees, winding drives, a central park, and scattered smaller green spaces. Azaleas and rhododendrons (Johnson’s favorite flower) were planted at the neighborhood’s heart – Springvale Park.

The next summer Johnson was furiously at work attempting to get the property just west of the Sweetwater Park Hotel in Salt Springs, present-day Lithia Springs, in shape for the Piedmont Chautauqua. Newspaper accounts during the summer of 1888 count down the days until the Chautauqua would open and advised at least one hundred laborers would be needed to execute the design plan.

Both the hotel and the Piedmont Chautauqua have been the focus of my Douglas County research for several years. The Chautauqua was the brainchild of Henry W. Grady who had come across the education movement during his travels in New York. He believed the concept which included lecturers, debates, various classes, and musical concerts would go a long way to stimulate intellectual growth across the south. The Piedmont Chautauqua would be held each July and August beginning in 1888. I’ve often explained the Piedmont Chautauqua would be like attending a seminar lasting several days or convention today.

While he attempted to raise money for the project, much of Henry W. Grady’s personal fortune was used to fund it. Sadly, the event never really caught on or made much of a profit.

Johnson’s landscape design for the Chautauqua grounds included a mound of earth that measured forty-two feet high and one hundred feet wide. Various accounts state that the mound was covered with 4,000 rose bushes. A winding path led up to the top of the rose mound, as it was called, where a wooden shelter stood entwined with rose vines. At each curve along the path were beds filled with daisies, pansies, and geraniums.

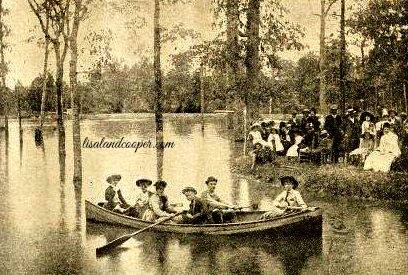

Part of Johnson’s plan included Lake Erskine, a lake that would grow to a “magnificent sheet of water” from a small pond due to a dam that was one hundred and fifty feet across. Water was pumped through a mile of pipe. The depth of the lake would be “uniform and shallow” making it perfect for the group of twenty-five paddle boats that had been ordered. Four islands and a fountain were included in the design of the lake see below.

Some of Georgia’s earliest electric lights illuminated the grounds each night during the Chautauqua, and the day’s festivities ended each evening with a fireworks display.

Various accounts mention that Joseph Forsyth Johnson participated in landscaping parts of the Sweetwater Park Hotel grounds as well so that the two properties would blend. He terraced part of the hotel grounds, laid out walks and drives, and planted various trees and flowers.

While there are some accounts that tout some of the nation’s wealthiest citizens bearing last names such as Astor and Vanderbilt as well as other famous people visited the hotel and Chautauqua at Lithia Springs, I have yet, after more than ten years of research, been able to verify one of them. There were several well-known people of the day I have verified such as Joel Chandler Harris who visited the hotel often, and the romance between General James Longstreet (1821-1904) and Helen Dortch Longstreet (1863-1962) sparked to the point it led to their marriage in 1897.

The Piedmont Chautauqua hosted many well-known speakers of the day including President William McKinley who at the time of his Chautauqua speech was a U.S. Senator. His topic was the tariff.

Henry W. Grady died in December 1889. The Piedmont Chautauqua was held a few more sessions before it eventually died out. By 1902, the property was in ruins, and today, there is little indication it was ever there. Even Lake Erskine is gone.

I have found hints that Joseph Forsyth Johnson may have worked on the landscaping design for the Georgia State Capitol Building that was completed in 1889. The only proof I’ve found, however, is that he was in Atlanta at that time. Another landscape projected credited to Johnson is at the Milledgeville Georgia Lunatic Asylum/Central State Hospital that Johnson would have worked on in 1887. The paperwork nominating the site for the National Historic Registry notes Johnson was likely the designer of the plan which included a series of winding drives, a large park, and a site for a lake.

Between 1890 and 1906 Joseph Forsyth Johnson worked steadily in various locations. He completed a major job in Chattanooga where he worked for a syndicate of Chattanooga and Boston capitalists who were setting up parks, streets, and boulevards. He set up parks in Fort Valley, Smithville, Albany, Cuthbert, Eufaula, and Union Springs. Many of these jobs were entrusted to him via the Macon Railroad. They had complete faith in Johnson due to his work at Salt Springs/Lithia Springs where the Chautauqua grounds were said to be the most beautiful in the south. He also was the landscape architect for Latta Park in Charlotte, North Carolina which was described as a “modern Eden” once he completed the work.

In 1898 Johnson published a second book, Residential Sites and Environments, Their Conveniences, Gardens, Parks and Planting and at some point, in 1904 or 1905 he published an article titled The Laws of Developing Landscape, Showing How to Make Thickets and Woodlands Reveal Their Natural Beauty in the Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society.

In early July 1906 it was announced Johnson would take on a new job in Cumberland, Maryland supervising a new park. It was not to be, however. Joseph Forsyth Johnson died on July 17, 1906 at Brooklyn Hospital. The funeral was held the next day, but there was no family there to attend the ceremony held at Brooklyn’s Evergreen Cemetery. I’m a bit uncertain if his American family knew his whereabouts, but Johnson’s British family thought he was already dead, and no one notified them of his “second death.”

Johnson did return to Great Britain to visit his family making the crossing several times late in his life but following one of Johnson’s trips his American family was notified he had died during the voyage, and he had been buried at sea. He abandoned his second family much like he had abandoned his first leaving no reasons why.

Johnson’s American family remained in the Atlanta area. His children were Roy Albert Johnson (1886-1939), Cecil Forsyth Johnson (1887-1951), and Edwina Johnson Mundy (1891-1969). Cecil became a major real estate developer and was vice president of Randall Brothers, a building materials firm.

His two families were not discovered until his great-grandson, the British entertainer Sir Bruce Joseph Forsyth-Johnson (1925-2017) signed on to explore his family history on the BBC program Who Do You Think You Are? Folks my age might remember he played Swinburne in Bedknobs and Broomsticks in 1971. He was shocked to find a family secret. Bruce Forsyth further discovered his great-grandfather lay in a grave with no headstone and had died with only $389 to his name. The headstone situation was quickly rectified.

Joseph Forsyth Johnson’s death notice in Gardening magazine simply but accurately stated, “In short, Joseph Forsyth Johnson helped show the south how to bring nature into the city.”

That he did. It’s just a bit sad that very few know this, and that Frederick Law Olmstead (1822-1903) and his sons get much of the credit since in many instances they came along behind Johnson and worked on the same locations including Piedmont Park prior to the Cotton States and International Exposition (1895).

Leave a Reply