What makes a good plot line for a story?

First, I think you need interesting characters who are captivating enough to give up a few minutes of your time and allow yourself to be drawn into the story. Add in some great details – a poignant love story, heroic deeds during wartime, a tragic loss combined with a mystery and you have a genuine blockbuster.

When I was in the classroom and even now as I write articles, columns, books, and even social media posts I look for the details of history that will enthrall others, old and young alike. I also look for the quirkiness of history, and the stuff of history that make it alive and worth remembering. This was especially important when I was in the classroom because the long list of historical events and skills students must master are a bit boring. Tackling these standards in a “just the facts ma’am” kind of format will often lead to a room full of students with glazed over eyes and off task behaviors – doodling, throwing spit balls, reading ahead in the text, scrolling through cell phones or tablets, or worse.

The Civil War is a broad historical topic full of facts and no matter the state the teaching standards are quite clear as to what students should know. The Civil War is also a historical topic that is jam packed with great stories and wonderful, real characters that can be used to motivate students to delve deeper into the content and analyze the context of the times and the motivation behind all the parties involved.

One of those stories involves the CSS Hunley, a submarine of the Confederate States of America. The Hunley’s story is interesting not just from a naval and technological viewpoint, but since I must consider my audience (from nine to ninety) and what will drag them kicking and screaming to the historical roundtable, the Hunley’s story is a gem for any serious teacher or author of history.

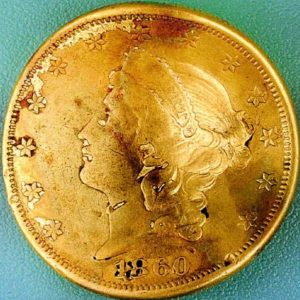

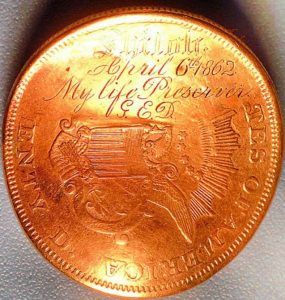

My first attempt to draw students and readers into the lesson would be presenting them with the front and back images of a gold coin and advising this coin has a story to tell. Take a close look, look at the engraving, what does this mean? How does this coin connect to a Confederate submarine?

This gold coin belonged to a Confederate soldier named George Erasmus Dixon (1837-1864), and it was given to him by his sweetheart, Queenie Bennett, as he headed off to war. Throughout our great history men have gone off to serve our country and have received parting gifts from their loved ones. During the Civil War soldiers received miniature paintings or photographs of their sweethearts or wives, a handkerchief, scarf, or even a tender love letter.

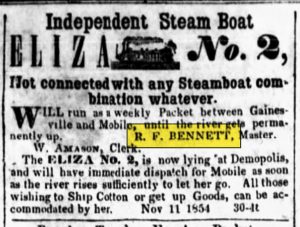

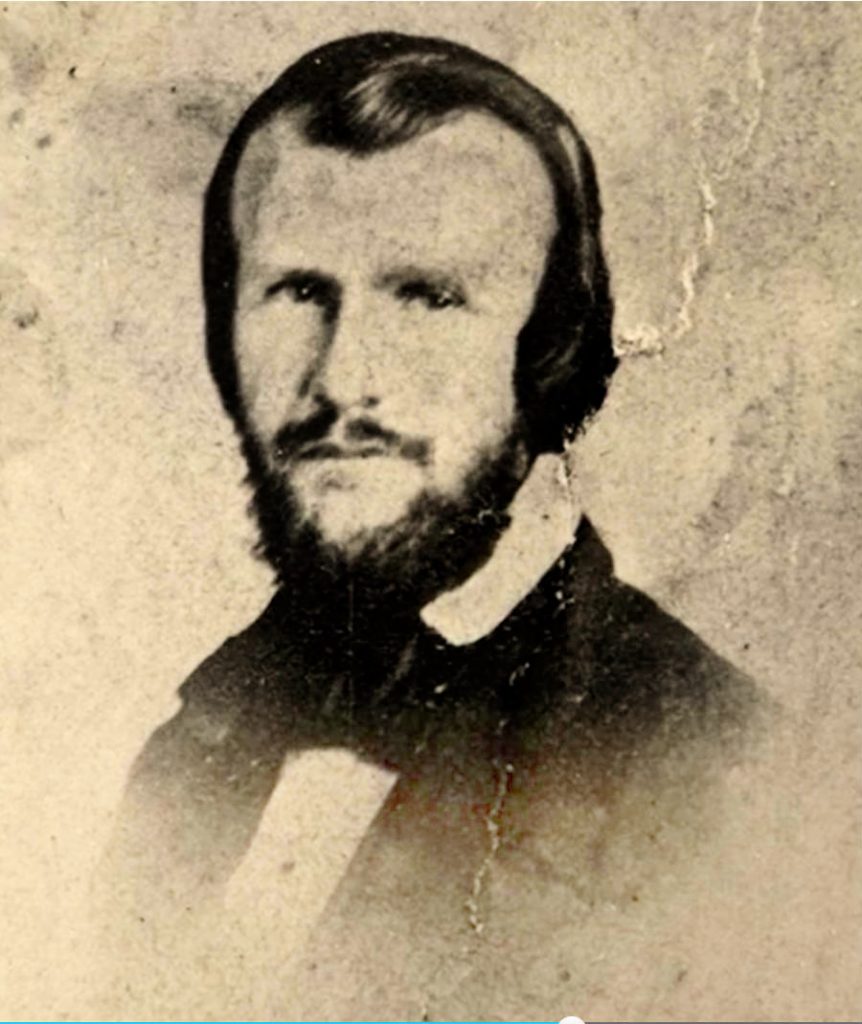

Queenie Bennett was the daughter of Robert F. Bennett (1818-1869) and Sarah Elizabeth (Skinner) Bennett (1829-1902). The Bennett family lived in Mobile, Alabama at the corner of Dauphin and Jefferson Streets. She was a very beautiful girl as this photo shows.

Queenie’s father operated and owned riverboats that ferried gamblers and freight up and down the Mississippi River. George Dixon and Queenie met on one of her father’s boats as early as 1860 when he worked on one of her father’s steam ships, and according to family stories it was love at first sight. It didn’t matter that she was just a young girl, and he was a few years older.

The Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp in Belleville, Illinois is named for George E. Dixon. Their website states, “Lt. George E. Dixon, the namesake of our camp, was…[nearly six feet tall…], a young and athletic man with sandy blond hair. Though he was originally believed to have been born in Kentucky, Doug Owsley, the forensic expert from the Smithsonian, believes Dixon was most likely born in the mid-west, possibly Ohio. He was a man of at least some wealth as indicated by the gold fillings found in his teeth, his diamond studded jewelry and an ornate gold watch he carried in his pocket. Thus far, Dixon’s history can be traced to 1860 when he was a steamboat engineer traveling the Mississippi River between St. Louis and Cincinnati, Ohio.”

“When the Civil War began, Dixon was in Mobile, Alabama. For the first years of the war, he became a part of the Mobile community and even joined the local Masonic lodge. Dixon joined the Mobile Grays, a local police force. In October of 1861, he enlisted in the Confederate Army and was assigned to the 21st Alabama Volunteer Regiment.” He entered as a Sergeant with Company A – Washington Light Infantry – and was a First Lieutenant when he was injured at the Battle of Shiloh.

As Dixon left Mobile to go to war Queenie handed him a gold coin, the same one pictured above. Dixon instantly placed the coin in his pocket where he carried it into war. Can’t you see him sitting around a campfire at night pulling out the coin, turning it over and over in his fingers, thinking of Queenie…thinking of home?

What was given as a token of love ended up serving a more important purpose. On April 6, 1862 at the Battle of Shiloh the coin stopped a bullet from injuring Dixon’s leg. Dixon would have a lasting limp from the injury, but he survived because of Queenie’s coin that he carried in his pocket.

When George returned to Mobile, he had the coin inscribed – Shiloh, April 6, 1862 – My life preserver – GED, and he continued to carry the coin in his pocket as a symbol of his love and devotion to Queenie as well as commemorate his experience at Shiloh.

George was unable to return to the battlefield but continued to serve the Confederacy. He was assigned to garrison duty and later volunteered to work with a new type of weapon the Confederacy was investigating. It was a new type of boat called a submarine. It was hoped the submarines would allow the Confederacy to bust the blockade that had blocked Charleston’s harbor as well as several other Confederate harbors.

Horace Lawson Hunley was a lawyer and former Louisiana State legislator who became involved with submarines securing the funding for what would become known as the CSS H.L. Hunley. Two other attempts for a working Confederate submarine had been made – the Pioneer tested in 1862 but later scuttled as the Union advanced on New Orleans and the American Diver where the builders experimented with electric and steam propulsion for the new submarine, before falling back on a simple hand-cranked propulsion system. American Diver foundered during bad weather at the mouth of Mobile Bay and sank. The crew escaped, but the boat was not recovered.

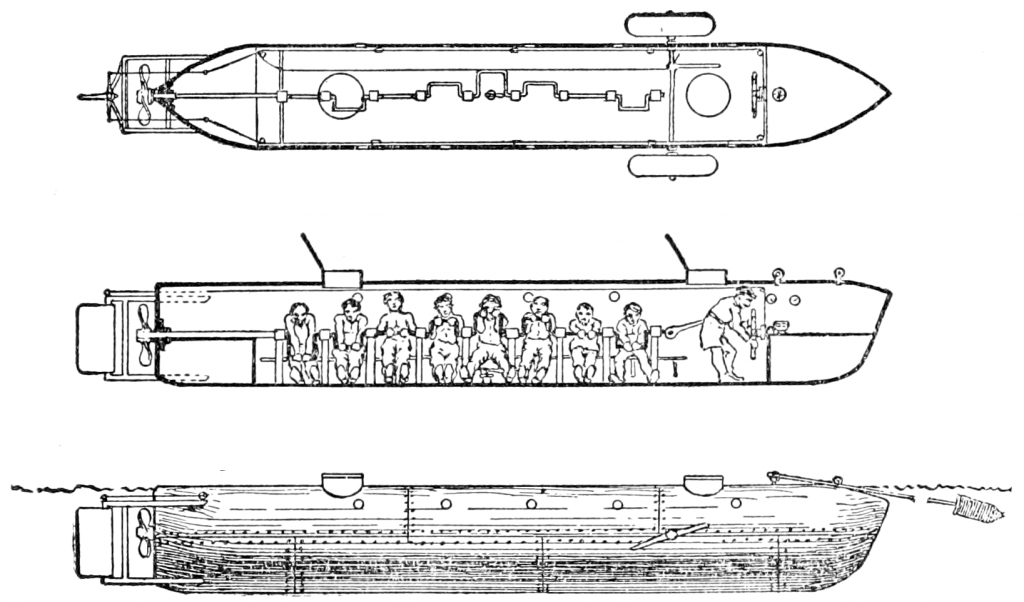

Construction on what would become the Hunley started soon after. Learning and experimenting as they worked, the men molded iron plates into a sleek shape. There would barely be room for eight or nine men, sitting on a wooden bench, turning the shaft that moved the propeller. A long pole was affixed to the front of the submarine. It would hold an explosive, which would be jammed into the hull of an enemy ship.

By July 1863, Hunley was ready for a demonstration. Supervised by Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan, Hunley successfully attacked a coal flatboat in Mobile Bay. Following this, the submarine was shipped by rail to Charleston arriving on August 12, 1863. Soon after it arrived the submarine was named for Horace L. Hunley. While sometimes referred to as CSS H.L. Hunley, the submarine was never officially commissioned into service.

On August 29, 1863, the Hunley was prepared to make a test dive when the lever controlling the sub’s diving planes was stepped on accidentally causing the Hunley to dive with one of her hatches still open. Three crew members escaped, but five drowned. Another accident occurred during a mock attack when the submarine failed to surface, and all eight crewmen died including Horace L. Hunley. The Confederate Navy once more salvaged the submarine and returned her to service.

Even though there had been setbacks and lives lost, George Dixon’s confidence in the Hunley remained high, and he was set to oversee the crew in February 1864 when plans were made to attack Union ships that were blocking Charleston’s harbor.

Queenie Bennett traveled to Charleston to spend some time with George before the attack. They were able to celebrate Valentine’s Day together. George gave Queenie a locket necklace containing his photo engraved with the words Forever in my heart. George and Queenie – February 14, 1864, and he stifled any fears Queenie might have regarding his safety by reminding her he carried her gold coin.

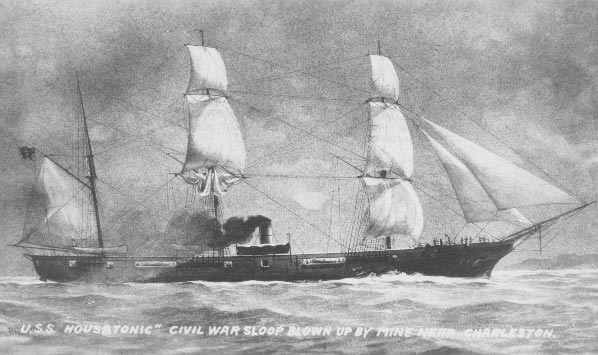

The Hunley would attack the USS Housatonic, a screw sloop-of-war belonging to the U.S. Navy on the night of February 17, 1864. Its namesake was the Housatonic River that flows through western Massachusetts and western Connecticut.

A lookout on the Housatonic observed an object moving towards the ship on the starboard side. The Housatonic began firing, but the Hunley was successful at planting the torpedo in the Housatonic’s hull. The Hunley pulled away and the explosive was detonated perhaps when George felt they were a safe distance away. The Housatonic sank killing five. While the Hunley is remembered as the first combat submarine to sink a warship, the Hunley was not submerged completely, and sadly, she never returned to base.

Family stories related how Queenie was shopping in Charleston’s City Market when she heard the terrible news. She was so distraught her father had to travel to Charleston to escort her home to Mobile.

Life did eventually move on for the distraught Queenie. I found a Mobile City Directory from 1871 that shows she was employed at Barton Academy as a school teacher. She married William Henry Walker on October 5, 1871. He was a longtime friend and like George Dixon he was a veteran of the Battle of Shiloh. The 1880 census indicates Queenie and her husband were living in Mississippi with five children. Tragically, Queenie died in 1883 due to complications following the birth of twins.

The Confederacy tried to keep the loss of the Hunley secret, hoping that the Union would fear more attacks, but any hope of ending the Union blockade disappeared with the missing submarine and Queenie’s beloved George.

Over the years quite a few myths surrounded the Hunley and her disappearance.

P.T. Barnum, a late nineteenth century circus owner, offered a reward of $100,000 to anyone who could find the Hunley for him to display in his traveling show.

More than one hundred years after the Hunley disappeared, famed author Clive Cussler, arrived in Charleston to begin his search for the submarine. He was a Civil War expert, an underwater archeologist, and an author. “Shipwrecks,” he liked to say, “are never where they are supposed to be.” Cussler and his team kept looking, on and off for fifteen years.

The Hunley was finally located on May 3, 1995, but it was not raised until August 8, 2000.

One of the books I used in the classroom to draw students into studying the Civil War is The Story of the H.L. Hunley and Queenie’s Coin by Fran Hawke and illustrated by Dan Nance (2004). The book, which can be viewed and purchased here is a wonderful story to share with history students from nine to ninety. The story motivates students of all ages to learn more about the submarine by drawing them into the tragic love story of Queenie and George, and by strategically interchanging the back story and the historical record back and forth in such a way you are totally unaware that you are learning something.

But what of Queenie’s gold coin?

Maria Jacobsen, the chief archaeologist sifted through the area where George Dixon would have sat. Through the mud she saw the glint of the lucky gold piece.

The coin is displayed today at the Hunley Exhibit at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center.

This isn’t my only article regarding the Confederate Navy. In March 2023 I wrote about Georgia’s Confederate Naval Yard along the Chattahoochee River that you can read here.

Leave a Reply