Little did I know when I drove into the cemetery at Sweetwater Baptist Church a few weeks ago that I would encounter the tallest grave marker I’ve seen to date in my walks across the burial grounds of old Campbell and Douglas County. I discovered a family story mired in wealth, greed, over indulgence, and suicide, and murder.

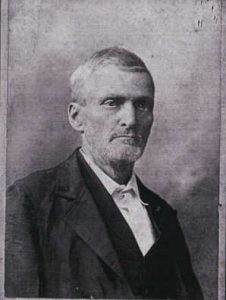

The large H on the marker stands for the surname Hight, and information regarding each of the four family members can be found on each side of the large spire. The family’s patriarch was James Lawrence Hight, Sr. born April 11, 1830. He was the son of Wiley Gilbert Hight (1786-1868) buried at Cave Springs Cemetery in Floyd County. The family traces back to John Hight who was born around 1634 and came to Virginia in the 1680s.

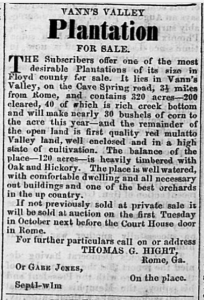

The Hight family was prominent in Floyd County. Soon after the death of Wiley Gilbert Hight in 1868, his 320-acre plantation located in the Vann’s Valley section of Floyd County was up for sale. Two of his sons, Thomas Gilbert Hight (1823-1870) and Fielding Hight (1818-1876) were well known for their business and political activities. Fielding represented Floyd County in the state legislature in the early 1870s.

A humorous story involves another relative, John Hight, who met up with General Tecumseh Sherman in 1879 when his train stopped at Cave Springs. General Sherman felt that John might be too young to remember General Sherman’s “sojourn” in Georgia during the Civil War, but John assured him he did remember him. When pressed for details the young man told General Sherman, “I remember you very well. I distinctly remember you burning my father’s gin-house and seventy-two bales of cotton.” Newspaper accounts did not relate if General Sherman made a response.

Focusing again on the cemetery marker and James Lawrence Hight’s story, I have no idea why he set out from Floyd County and moved to Paulding. Perhaps he felt a little overshadowed by his brothers and wanted to make his own way without their accomplishments influencing his success, but no matter the reason, he set off on his own.

The 1870 census indicates he was a land trader living at Dallas in Paulding County. A land trader is what you might think of today as a “property flipper.” He married Sarah R. (Thompson) Hight (1847-1887) on November 21, 1871. She was the daughter of Reverend Steven Alexander Thompson (1825-1886) who was living in the California section of Paulding County in 1870. Later, he moved on to Alabama.

Sadly, Sarah would pass on June 15, 1878 leaving James, Sr. alone with their two young sons.

The next year he was listed as a “land agent” in the Dark Corner section of Douglas County in “Schole’s Georgia State Gazetteer.” More than likely James, Sr. received his mail at the Dark Corner post office while living not too far away over the Paulding line. The 1880 census indicates he was living with his two sons James Lawrence, Jr. and Emmett, ages 6 and 3 respectively, in Paulding County adding widower and farmer to his land agent status.

In mid-April 1883, James, Sr. purchased what was described as an elegant tract of land just beyond the railroad on the Buchanan Road in Dallas. Hight was planning on making improvements to the land including developing a fish pond and stocking it with the finest of fish. Unfortunately, almost a year to the day later, Hight suffered a reversal of fortune when his new residence burned to the ground. He managed to save some important papers and a few pieces of furniture, but it was a total loss.

By 1895, James, Sr. had moved to Atlanta living on Pryor Street, Highland Avenue, and finally settled in 1900, in Decatur, where he lived with his two sons on Sycamore Street. Also living with the men was Ella Burks, an African American cook. More than likely the home they lived in still stands. Today, Sycamore Street is known for its large and historic homes. Originally the street was known as the Covington Road and served as the stagecoach route to Augusta through Covington, Madison, and Eatonton.

While many of the men who speculated in Atlanta real estate around the turn-of-the-last century were rather flashy regarding their deals making sure their names were constantly in the newspapers, James, Sr. was very quietly going about his business acquiring not only key properties in Atlanta, but major properties all across the state of Georgia. He would sell some of the properties for huge profits, he would also keep some and live off the rental and leasing fees he could charge. Occasionally, he was mentioned in reference to lawsuits he filed to obtain monies due him, but that’s about it.

Tragedy would once again enter James, Sr.’s life when his oldest son and namesake, James Lawrence Hight, Jr., joined his mother at the Sweetwater Baptist Church cemetery in August 1899. James was only 25 years old, and as prominent as his father was, I found no mention of his death including notice of a funeral, so it’s unclear if he died of sickness, by accident, or by his own hand.

After the turn of the last century, James, Sr. gradually began turning over more and more of the land business to his surviving son, Emmett, a graduate of Mercer University and member of Sigma Nu Fraternity. In 1903, James, Sr. placed various ads in newspapers advising anyone who owed him money for land sales or through loans should make payment arrangements with Emmett at his office located at 39 N. Forsyth Street in Atlanta. James, Sr. also added that if a lawsuit had to be filed, he would tack on an extra ten percent to cover the attorney’s fees. As I read through the various court notices and sheriff’s sale ads where James, Sr. was the beneficiary I could help picturing the character of Snidely Whiplash, archenemy of Dudley Do-Right and who was always tying Dudley’s girlfriend, Nell, to the railroad tracks.

While his father was very lowkey regarding living his life, Emmett Hight was the complete opposite. Stories of Emmett’s exploits began to hit the Atlanta newspapers by 1902. In June of that year Emmett was involved with a shooting incident along the Chattahoochee River during what was termed a “fishing frolic” that “created a sensation.” Emmett, along with J.A. Mullins, and two women – Mary Raymond and Mrs. R.H. Freeman – provided a tale that was so mixed up the police who responded to the scene had some difficulty sorting it all out. Some of the witnesses stated Mullins had accidentally shot himself, and others stated Mrs. Freeman fired the pistol. The officer ended up arresting all four.

Four years later Emmett was sued by a man who charged him with alienation of affection claiming Emmett had taken his wife and persuaded her to live with him. The lawsuit demanded $25,000 and said that Emmett “with the cunning of a serpent invaded the home of the [husband] and destroyed his home life and happiness.”

I’m not sure what Emmett did with the woman because he married a Columbus socialite on January 6, 1909 named Carrie Estelle Deaton, the daughter of Eugene Deaton, a wealthy wholesale grocery merchant. Newspapers described the bride as having a charming personality and intellect. The wedding was a large and beautiful affair taking place at St. Luke’s Church in Columbus followed by reception at the Deaton home on Second Avenue. Emmett and Carrie took a two-week trip to Florida and then returned to the Hight home in Decatur.

James, Sr. would pass six months after Emmett’s wedding on June 6, 1909. It was only then that a true picture of his wealth was placed in the newspapers describing James, Sr. as “probably the largest individual land owner in Georgia.” It was stated he had “accumulated a vast fortune, estimated at a million and a half dollars, through his careful investment and keen insight into real estate.” Through his final days he had remained in control of his business activities with some noting he had “remarkable control of his mental faculties for an 80-year-old man.

It was noted in the newspapers a special rail car would be attached to the Southern train leaving Atlanta on Tuesday morning, June 8th at 6:30 a.m. for those who wanted to attend the funeral which would be held at Sweetwater Baptist Church. Officiating the funeral would be Reverend T. Monroe Spinks of Atlanta. Following the funeral James, Sr. would join his namesake and his wife in the church’s cemetery.

Of course, it was no surprise that Emmett was the main beneficiary of James, Sr.’s estate. Emmett’s maternal aunt, Mrs. G.G. Pace or Evalea (Thompson) Pace, was named in the will in a much smaller capacity. The estate was so vast it would take a year and a half to settle due to the amount of work it took to inventory James, Sr.’s holdings and issue all the necessary deeds to transfer the properties into Emmett’s name. Acquiring new properties was basically put on hold so Emmett could be at the beck and call of attorneys who required his signature daily.

Finally, the estate was settled and by the first of October 1911, Emmett could resume business at brand new offices in the Empire Building located at the corner of Marietta and Broad Streets. Construction on the building began in 1900, and it was the first steel-frame and tallest building in Atlanta until the Candler building was erected in 1906. In later times the building was known as the Citizens & Southern National Bank building, and today carries the name J. Mack Robinson College of Business, a part of the Georgia State University campus.

In an “open for business” article it was reported Emmett owned property in 22 different Georgia counties and was intending to do a large business, not only in Atlanta property but in lands and developments all over the state. While his father had steadily built a large fortune and portfolio of properties throughout his life, Emmett had built a sizeable business of his own.

It was noted that in just 15 years, the progress and growth of Atlanta had forced Emmett to move his office 8 times. He had started out with an office at 88 South Forsyth Street paying on $1 per month as rent! Also, his new offices in 1911 in the Empire Building was on the same lot where he had once had offices in a totally different building.

The future looked bright. Emmett had a staff of real estate agents handling the nuts and bolts of his business. This left him free for the frat-boy and sportsmen activities he had grown to love.

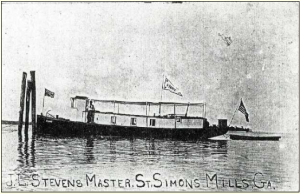

In December 1911 he took a trip to southeast Georgia to the Brunswick area courtesy of Captain John Lawrence Stevens (1852-1929), a well-known Georgia coastal captain whose family had property at Frederica. The group of hunters, including Shelby Smith, Ed L. Grant, W.J. Stoddard, T.C. Ladson, E.L. Waggoner, and Dr. E.C. Branyon, were met by Stevens and boarded his launch named “Annie” where they were served an elegant breakfast aboard the boat. Once underway the “Annie” took the group “down the bay, across St. Simons sound, up Frederica River, stopping an hour to view the Oglethorpe Fort, the Wesley Oak, the oldest church in the United States and the bloody marsh, they arrived at Captain Stevens’ beautiful home at Frederica, where Mrs. Stevens served refreshments with oranges plucked from the overladen trees in her yard.”

The Annie, seen below, was a workboat used by Captain James Lawrence Stevens to haul passengers and supplies along the Georgia coast.

The party then sailed up Frederica, Hampton and Altamaha Rivers finally arriving at their hunting grounds. At daylight the next day they landed and proceeded on the hunt, which proved very successful, bagging eleven deer in two and a half days.

Below is an image from the hunt that appeared in the Atlanta Georgian and News for December 2, 1911. From left to right: Emmett Hight, W.J. Stoddard, and Ed L. Grant.

Emmett was involved in another shooting incident around 3 a.m. on July 2, 1912. Following last call and the shut down of the city’s bars, Emmett was looking for a drink. He came upon the night watchman at the Walton building and told him he needed a drink. Emmett was already drunk enough, but a night watchman showed him into the offices of the Georgia Fruit Exchange anyway where employees were working extremely late because they were at the height of the peach season.

Later, the clerk, R.Z. Upchurch, would tell reporters he knew of Emmett’s reputation regarding his drinking and other unfavorable reports regarding his reputation and was a bit resentful at having the man in his office making drunken demands, but he gave Emmett a drink anyway. At some point words were exchanged, a fight ensued, and Emmett ended up shooting Upchurch. The bullet came dangerously near the heart and penetrated through the back, but Upchurch would live.

Fellow employees took Upchurch to the hospital while the night watchman carried Emmett to the nearby Elkin-Goldsmith Sanatorium on Luckie Street where he had his wounds dressed and was asleep when the police officers found him at daybreak. Later, Emmett’s only statement regarding the matter was Upchurch was the aggressor, and he had only fired the gun in self-defense.

Apparently, during the next three years Emmett spiraled deeper and deeper into alcoholism to the point he developed alcohol paralysis, an alcohol-related neurological disease caused by ingesting toxic amount of alcohol. By 1915, Emmett was in a wheelchair needing the constant care of a nurse and described as a shadow of his former robust self. The addition of round-the-clock nursing care also caused a complete breakdown of Emmett’s marriage…not that it really needed any further help to disintegrate.

The photo below appeared on the first page of The Atlanta Constitution dated January 10, 1915, Emmett Hight is seen in his wheelchair with son James Lawrence (born 1911) sitting on an ostrich photo prop. Nurse Nettie Davis is seen between the two.

Hight had been living in his Ansley Park home for some time, a location where many of Georgia’s wealthiest families lived. The Hight home was at 90 Peachtree Circle and still stands. At the time the Hight family moved in the home it was described as “richly furnished, artistic in design and appointment.”

Carrie Hight often clashed with the constant round of caretakers and nurses who cared for Emmett accusing them of “taking over” her home and turning her husband against her. In November 1914, Carrie and Emmett would separate just two months after the arrival of Nettie Davis, the latest round-the-clock nurse placed in the home by Emmett’s doctor.

By January 1915, a war of words was fought in the newspapers between Emmett, Carrie, and Nurse Davis regarding the news Carrie had filed for divorce papers. The Atlanta papers published daily accounts regarding the scandal. Court papers revealed Carrie was asking for half of her husband’s fortune which was then estimated at $500,000. The papers also alleged Emmett had turned over the entire affairs of his home to Nurse Davis, and he made a regular practice of carrying the nurse to cafés and the theater in preference to his wife. Drunkenness, cruel treatment and neglect were other charges. Carrie accused her husband of threatening her life at various times, one of which when he drew a pistol and fired it. There were also claims he had forced himself into the home at least once at the point of a revolver. Once inside Emmett was alleged to have slapped Carrie and cuffed her. Alcohol abuse was listed as the cause of the domestic troubles and Emmett’s physical paralysis.

While some of these charges could have been “divorce drama,” it was well known that Emmett would be seen out in his chauffeured drive car with his nurse daily as it was sometimes necessary for him to leave his home to take care of business.

At one point in dramatic fashion appropriate for a made-for-television movie Carrie and a sheriff’s deputy pulled up in front of the Hight home in separate cars. The deputy was going to serve the divorce papers on Emmett, but Carrie managed to get there in the nick of time. Even though the papers had not been served on Emmett, a judge still granted a temporary injunction barring Emmett from disposing any of his property. The “no service” issue shows Carrie almost instantly regretted her decision and the case was held in suspension for several days.

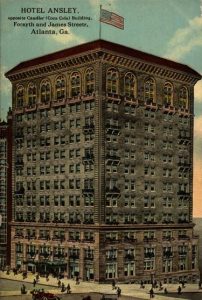

Carrie had been staying at the Hotel Ansley with the couple’s son, but on Wednesday, January 6th after a phone conversation where the cook, Connie Ellison, served as the go-between for the warring couple Carrie agreed to return home. A place-setting was placed on the supper table for Carrie in the Hight dining room and a maid readied her room and the room of little James Lawrence who was with his mother along with his nurse Lucy Wright, at the Hotel Ansley. The hotel was on the south side of Williams Street between Forsyth and Fairlie Streets. By 1952, it would be known as the Dinkler Hotel.

Later in the day, Carrie called her home again to make sure Emmett would pay the hotel bill. This time Nurse Davis answered the phone and served as the go-between. Of course, an argument ensued. Carrie accused the nurse of having an “affair of the heart” with Emmett. Nurse Davis ended up hanging up on Carrie who then traveled to Columbus with her son to confer with her father. Carrie stated, “If my husband failed to pay such a small thing as my hotel bill it is clear that he would not properly support [his] child and myself.”

Nurse Davis, who seemed to enjoy the attention in the newspapers making herself readily available to reporters, stood her ground and said she wouldn’t go until the doctor that placed her in the Hight home told her to leave or if Emmett told her go. Apparently, Emmett wanted her to stay.

The nurse was described as a trim, good looking woman, apparently between 25 and 30 years of age, readily made herself available to reporters. She had been born in Sandersville, Georgia and had aspired to be an artist. She gained a distinct local reputation as a sketch artist around the time she graduated from high school and went on to attend Andrew Female College at Cuthbert. During her sophomore year she had arrived in Atlanta to change the course of her future from art and possibly teaching to training at the Baptist Tabernacle infirmary as a nurse where she graduated in 1909.

Nurse Davis said she deplored the fact that news reports were one-sided with Carrie’s “story.” Nurse Davis denied there was any affair between herself and Emmett, and she accused Carrie of being partly responsible for her husband’s condition. She stated Carrie “created scenes” at her Emmett’s bedside as well as “creating demonstrations that aroused the neighborhood.” The nurse further claimed that these “nervous outbreaks” had been the reason why Carrie had gone to a private sanitarium recently. Carrie had mentioned her sanitarium stay in the divorce petition stating Emmett was the cause that drove her there, and she had told the newspapers that when she was being released from the sanitarium her doctor called her home and Nurse David told him Mrs. Hight was not wanted there. That was the reason why Carrie had gone to the Ansley.

Nurse Davis further stated she hoped the divorce proceedings would continue because it would give her a chance to take the stand and tell the truth about Carrie’s maliciousness saying, “[My testimony] would open eyes, ears, and hearts…I could tell some things that would make her regret she ever thought of divorce.” She also denied she had taken charge of the Hight home. Sure, she was superintendent over some of the household affairs, but this was because Carrie had neglected them, and there was no one else to do it.

Within a day or two Emmett had placed an advertisement in the newspapers in which he admonished tradespeople they weren’t accept any purchases to his accounts unless he personally authorized them, and he conferred with his attorneys awaiting Carrie’s next step. In response, and from her father’s home in Columbus, Carrie advised Nurse Davis was the obstacle that prevented reconciliation. She would not return to the Ansley Park home until Nurse Davis had left, and Nurse Davis was adamant that she was not leaving.

By the middle of the month it appeared some sort of agreement had been stuck. Carrie and little James Lawrence had returned home even though Nurse Davis remained at her patient’s bedside. Carrie dropped the divorce proceedings stating she had been misguided and had let gossips influence her actions.

The cloud of scandal over the Hight home was not entirely gone, however. Within a couple of days, the cook and chauffeur were in court answering to charges regarding a fight over “unwanted attentions.” In February, a nurse that had been employed prior to the infamous Nurse Davis sued the Hights for $5,000 alleging she was assaulted by Carrie while under their employ.

The reconciled Hights lived in a truce for only three months. Towards the end of March 1915 Emmett filed for divorce asking for custody of young James Lawrence and accusing Carrie of frequently aiming a shot gun in his direction as he lay paralyzed in his bed or threatening to beat him with a fire poker. Throw in additional charges of Carrie being a drug fiend and an unfit mother and another scandal was hatched.

Emmett further related in court papers that Carrie’s behavior had forced him to flee his home and seek refuge in a hospital. Carrie countered by filing a counterclaim and by blaming outside influences stating, “Emmett will never get that divorce. If there’s a divorce, I’ll get it.”

No further mention of Nurse Davis was made.

Before the divorce could be finalized, Emmett Hight died on Monday, May 17, 1915 making the Hight family cemetery marker complete once he joined his parents and brother at Sweetwater Baptist Church Cemetery.

Two days after Emmett’s passing it was discovered that certain personal property was missing that was valued at $2,000. The property included a diamond stud, a diamond ring, and watch, the latter of which was an heirloom that may have belonged to Emmett’s father, but I’m not certain of that fact. The diamond stud alone was valued at $700.

It was soon known to the public that Carrie was claiming to have been barred from Emmett’s bedside during his final hours. Jim Davis, Emmett’s long-time chauffeur told Carrie that Emmett had wanted her to visit. He was also a witness that Emmett had been wearing the missing watch and diamond ring in the hospital and the diamond stud had been kept where it always had been when Emmett was not wearing it – safely screwed into a special compartment in his clothes.

Throughout their marriage Carrie had related people sought to get Emmett’s money and interfered with their domestic affairs and caused all the troubles between them. This time the person or persons who intervened was not Nurse Davis, but Emmett’s maternal aunt Evalea (Thompson) Pace, who was mentioned above as a beneficiary listed in James, Sr.’s will. Pace had let it be known that she would be making a claim against the estate for $25,000 no matter if Carrie was deemed the nearest relative or if she was.

It was soon discovered that Pace had been at Emmett’s side during his final hospital stay and had been the one barring Carrie from knowing Emmett had asked for her. It was also soon discovered the missing diamond ring and watch were in her possession. The undertaker had given them for safekeeping to her when he took possession of Emmett’s body. No mention was made regarding the diamond stud, but it could be assumed it was given to Pace as well. She claimed these items stating Emmett promised she could have them from his death bed, and that Emmett never offered Carrie forgiveness or any reconciliation towards his wife.

The will was another major question mark. If a will existed, it would be followed and might possibly have named an heir other than Carrie. Evalea (Thompson) Pace was a strong contender.

Six days following Emmett’s death representatives from all sides gathered at the Hight home to open Emmett’s safe. Just one day prior to the safe being opened, attorneys had located $86,000 in bonds and other investments in filing cabinets in a private office Emmett kept in the Candler Building, a separate office from his real estate office at the Empire Building. Inside the safe at the Hight home were found $500 in currency and silver, a stack of deeds and other documents representing at least $500,000 in land, securities, and bonds. Much of the property was South Georgia farming land, and a little jewelry, but NO will, and because of this it appeared Carrie would become the administratrix of Emmett’s estate. She would maintain the Hight Realty offices at the Empire Building and retain the employees to operate and maintain the reality business Emmett had operated

There were challenges. Evalea (Thompson) Pace was not done challenging Carrie for control. She filed suit asking for $25,000 stating Emmett had promised her that amount during his last illness. It’s not clear if Pace ever received a settlement of any kind. It’s also unclear if Emmett’s diamond stud was found either. Evalea Thompson Pace would pass in 1932.

Eventually, things began to settle down. Carrie oversaw the vast holdings of her husband employing John O. Dupree, a well-known real estate man in Atlanta at that time. Young James Lawrence Hight was one of the most popular members of the graduating class of Oglethorpe University in 1932. He was a member of the Kappa Alpha fraternity, the Lords’ Club, an honorary scholastic fraternity. He was often mentioned in the papers hosting dinners and serving as a groomsman in various society weddings.

Life went on in the Hight home at 90 Peachtree Circle until the night of June 4, 1933 – a Sunday night. Earlier that day the mother and son had entertained Sunday callers – Mr. and Mrs. J.B. Osborn who lived on Piedmont Road and were longtime friends of the Hight family. Later, they would tell police how Carrie and her son were both in good spirits and nothing seemed amiss.

Below is a photo of Emmett Hight’s home in Ansley Park as it appeared in The Atlanta Constitution on January 9, 1915.

The bodies of mother and son would be discovered the next day at noon when neighbors became concerned regarding an air of silence surrounding the Hight property other than the constant and doleful barking of two pet dogs inside the Hight home. Deputy Sheriff Gordon Hardy would be the first to enter the house. He found lights in the living room burning. In an upstairs bedroom he found Carrie Hight lying across her bed with a bullet in her temple and her son was lying nearby on the floor with a similar wound and .32 caliber pistol lying near his hand.

Within minutes members of the solicitor’s office, crime scene investigators, and the coroner at that time, Paul Donehoo, was on the scene along with a gathering crowd of neighbors on the lawn including the family friend, J.B. Osborne, who along with his wife had been the last ones to see the mother and son alive. Mr. Osborne would later tell newspaper reporters that a neighbor told him two muffled shots were heard around 9:45 Sunday night, but the noise was quickly dismissed when it was suggested that an auto had backfired.

Mr. Osborne also reported other neighbors had told him that shortly after the shots sounded a youthful appearing man drove up in a closed automobile and went up on the Hight porch. After he rang the bell several times, he walked to James Lawrence’s car parked in the drive, looked inside and then returned to his car where he sat several minutes before he drove away. More than likely the mother and son were already dead in the upstairs bedroom when the bell was being rung.

Within a few hours of the bodies being discovered the police advised James Lawrence was a very depressed and troubled young man based on the evidence found in the home which included a series of notes which speculated on the morbid philosophies of life and statements such as “life is not worth living…everyone is lousy…my girl kicked me” and other statements written by the young man.

Another stated, “Nobody cares whether we are alive or dead. The world is no account anyway and I am going to get out of it.” After seven years of suffering he was going to leave “a sordid world and take mother along.” James Lawrence indicated a supreme love for his mother, who he said was “too nice to leave in this dirty world.”

Below is an image of J. Lawrence Hight, Emmett and Carrie’s only child, as he appeared in The Atlanta Constitution article announcing the murder-suicide on June 6, 1933.

On top of a stack of philosophical books James Lawrence had left the message, “Please read these books,” and attached to the note was a clipping from a column written by a well-known advisor in affairs of the heart. The clipping evidently contained a question he had sent the columnist, requesting advice regarding “a girl who is very selfish and who boasts of her conquests.”

Continuing in a morbid theme, the notes explained young Hight’s ideas of an after life. One note said, “Death is merely a chemical change. I am not going to heaven or hell, but will disintegrate, nothing more, nothing less. Seven years is long enough to suffer.” On a table in another room was a stack of checks, dated June 4 (Sunday) and attached to a sheaf of bills which they were to settle.

Sections of the note were couched in vicious language. Oaths were uttered in what seemed to be a spirit of hatred for people and the world. At the point where he discussed unrequited love he drew a line and left it blank for the name of the girl. Another note asked whoever found their bodies to notify John O. Dupree, the real estate man who handled their property affairs.

In the days following the murder-suicide it was learned James Lawrence had obtained the handgun from his friend, Julius Hughes, Jr. telling his friend “I’m going to scare up some people” and need a gun. James Lawrence had gone swimming that Sunday afternoon with his friend and classmate, Paul Goldsmith, who said James Lawrence appeared to be in good spirits. He asserted he knew of no love affair, and said that while he had been out Sunday night James Lawrence had called him.

From what can be determined from funeral notices Carrie Hight and her son joined the other four Hight family members in the cemetery at Sweetwater Baptist Church, but there is no Find-A-Grave entry for either. I’ve visited the cemetery twice looking for them. If they are around the Hight family marker they rest in unmarked graves. I still have no idea who ordered, paid for, or placed the impressive cemetery marker for the four Hight family members. I have to assume Emmett Hight ordered it following his father’s death, but that is just an assumption.

The Hight family fortune and the real estate holdings that included several valuable parcels became the property of Carrie’s half-brother and half-sister – Hugh E. Deaton and Dorothy Annie Deaton of Columbus, Georgia in May 1934 after a legal battle that included seven other claimants. Within thirty days one of the properties – a two-story building consisting of stores and an upstairs apartment on Whitehall Street sold for $10,000.

Below is an old photo of the marker showing what it looked like before the trees grew up around it.

Such a beautiful cemetery marker…such a sad story.

If you enjoyed this true history tale you will like my latest book – Georgia on My Mind: True Tales from Around the State which contains 30 true tales from all around the state including three stories from Atlanta, and yes, there will be volume two out soon! You can purchase the book here…in print and Kindle versions.

Lisa;

There was a Carl Hight that ran the Exxon Service Station at the corner of Roosevelt Highway and Campbell Drive during the 1970’s. Wonder if he is related

Chester