In the mid-19th century, the U.S. Army faced a problem: how to move people and supplies across the newly acquired, sunbaked deserts of the American Southwest. While there were a few short rail lines across areas of Texas as early as the 1850s, there were no railroads that extended into Arizona and New Mexico until 1877 when the Southern Pacific Railroad reached Yuma, Arizona. In the mid-1840s roads were scarce, water scarcer, and mules and horses often failed under the punishing conditions.

Enter one of the strangest ideas ever to come out of Washington, D.C. — the United States Camel Corps.

The camel plan didn’t start with a daydream — it began through a shared history of West Point and service during the Mexican American War between Major George H. Crosman (1799-1882) and Major Henry C. Wayne (1815-1883) both serving in the role of quartermaster at one time or another and had seen how hard it was to move supplies. Crosman who was serving as Assistant Quartermaster at Boston had been mulling an odd solution when the idea of using camels was given to him by the son of General James Miller (1776-1851), who was a well-known figure during the War of 1812 and served as the first governor of the Arkansas Territory. Crosman liked the idea and forwarded it to Major General J.S. Jesup, then Quartermaster General at Washington, D.C., but as these things often go, the man at the top was not amused or impressed.

Crosman’s friend, Major Henry C. Wayne was in Washington, D.C. at the time working in the Quartermaster General’s office and heard about the idea. He was intrigued and thought the proposal deserved serious consideration and began researching it on his own.

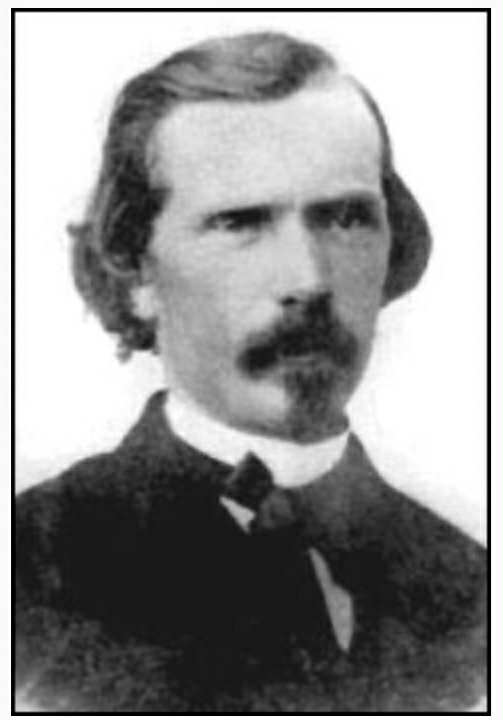

General Henry Constantine Wayne (1815–1883) of Savannah was the son of U.S. Supreme Court Justice James Moore Wayne (1790–1867), who built the Regency-style home at 10 East Oglethorpe Avenue between 1818 and 1820. Though Henry likely spent part of his youth there, the residence was sold in 1831 to his cousin Sarah Stites Gordon and her husband, William Washington Gordon; it later gained fame as the birthplace of Juliette Gordon Low, founder of the Girl Scouts.

I first learned of Wayne’s contribution to the U.S. Camel Corps when I read a few letters written to him related to a book I’m currently researching and writing. While I plan on writing a much more detailed regarding Wayne’s military exploits, I am only presenting his contribution to the U.S. Camel Corps for now.

By 1848, Wayne shared his study regarding the feasibility of using camels logistically by the U.S. War Department and various members of Congress including then Senator Jefferson Davis who was the chairman of the committee on military affairs. Senator Davis became an advocate and urged the adoption of the plan, but it was laughed out of committee. Davis, the future President of the Confederate States of America, remained an advocate until he resigned his Senate seat in the Fall of 1851 to run for Mississippi’s governor – an election that he lost.

Camels had thrived for centuries in North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia. Their ancestors had even roamed prehistoric North America during the Cenozoic era. Spanish and English colonists had tried importing them before, but the experiments failed.

Still, Wayne and Crosman continued to believe the time was right, and their chance came when Jefferson Davis was appointed Secretary of War in 1853 during the administration of President Franklin Pierce. Secretary Davis revived the proposal in his official reports and kept pushing until, on March 3, 1855, Congress finally appropriated $30,000 for camels and dromedaries “for military purposes.”

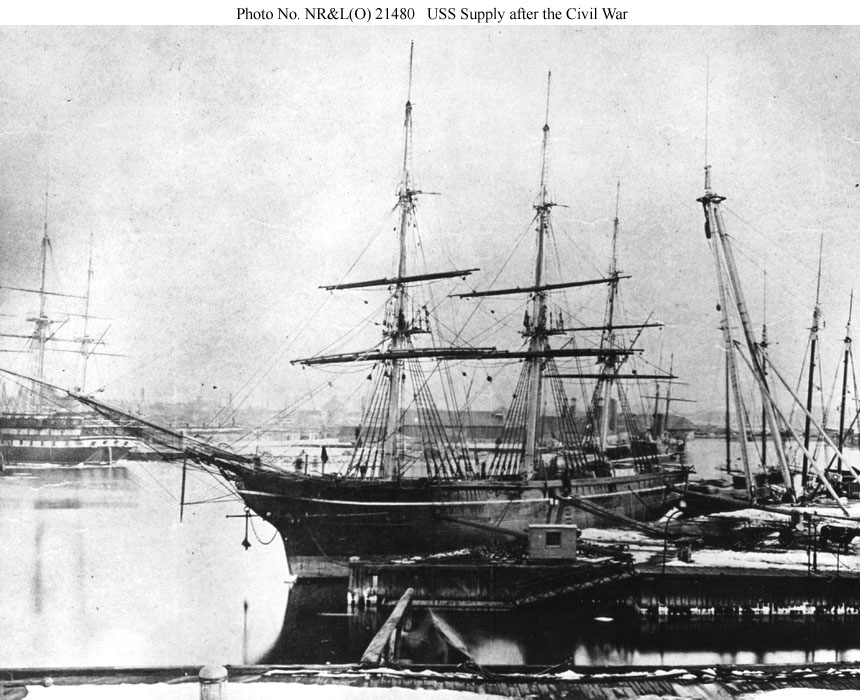

General Henry C. Wayne was put in charge of what became known as the U.S. Camel Corps. He partnered with then Navy Lieutenant David Dixon Porter (1813-1891). The men boarded the USS Supply and set sail to Europe and the Mediterranean.

In England, France, and Italy, they studied camel handling. In Tuscany, Wayne inspected a herd that had been working for two hundred years. In Tunis, he became the first official U.S. visitor to the Bey, who was Muhammad Pasha Bey (1811-1859) at the time and who presented two camels to Wayne as a gift to America.

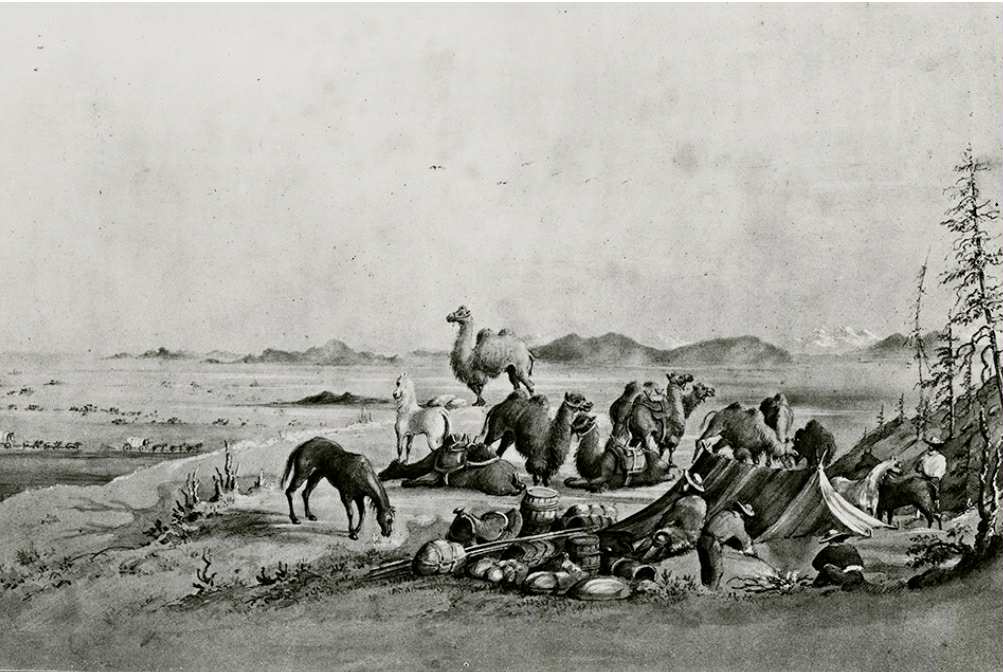

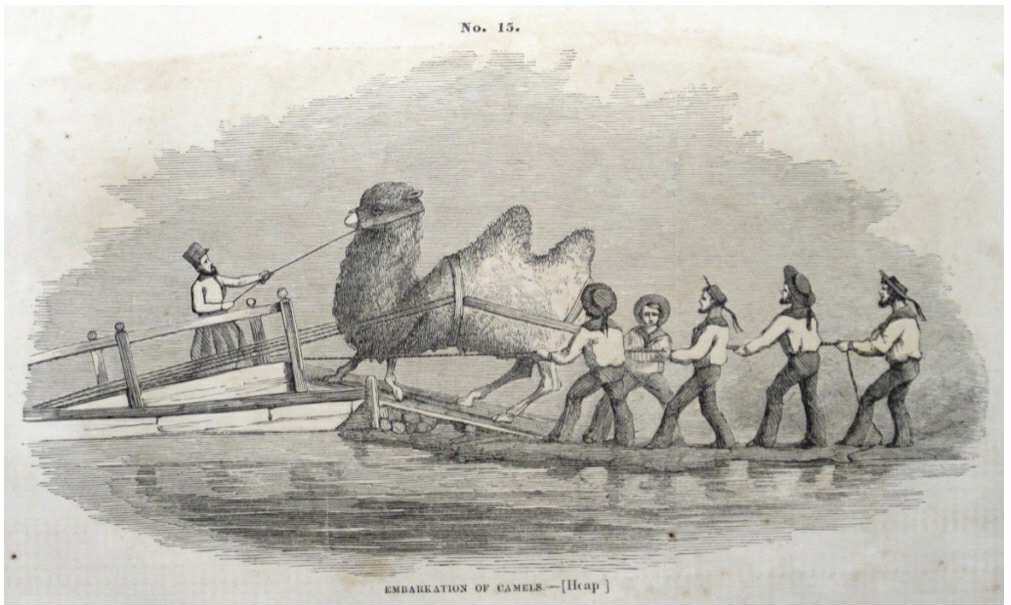

The men shopped for camels across Malta, Greece, Turkey, and Egypt — sometimes needing to bribe officials with American rifles — and eventually purchased thirty-three camels: nineteen females, fourteen males, including dromedaries (one hump), Bactrians (two humps), a hybrid cross of a dromedary and Bactrian referred to as a “booghdee,” and even a calf.

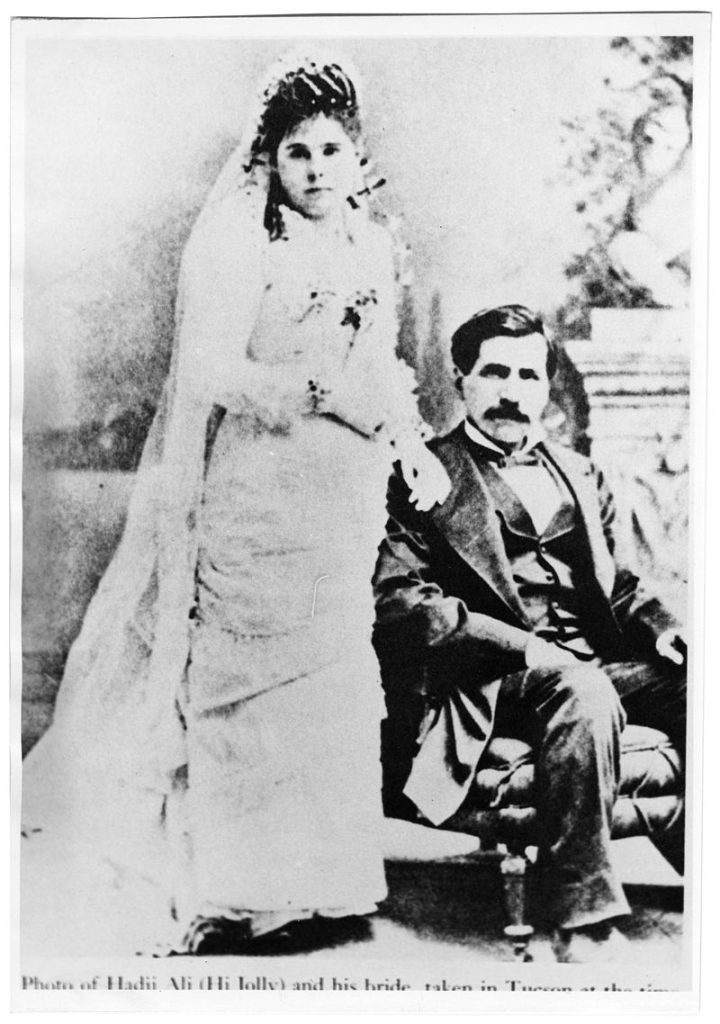

Five experienced camel handlers were hired, including two who would become legends in the Southwest: Hadji Ali who was referred to by the Americas as Hi Jolly and Greek George. These men would attempt to train the Army’s teamsters and hostlers in caring for the animals, how to mount and ride the camels, and how to pack a camel because it was tricky business to keep loads from shifting ending up on the ground.

On April 29, 1856, the USS Supply arrived at Indianola, Texas — one camel more than it had left with, thanks to a birth at sea. Texans gawked at the strange beasts, and horses and mules stampeded at the sight of them.

The herd moved inland to their headquarters at Camp Verde in Kerr County, Texas, stopping along the way for public demonstrations. Wayne put four bales of hay (over 1,200 pounds) on one camel to prove its strength — the crowd’s skepticism vanished when the animal calmly stood and walked off.

Tests showed camels could carry double the load of mules, travel faster, and go days without water. They plowed through mud that stopped wagon teams cold and thrived on desert forage. In one famous trial, six camels carried 3,648 pounds of oats from San Antonio to Camp Verde in two days — the same load took mule teams nearly five days.

Wayne dreamed of a breeding program, but the War Department refused. The goal was to test camels for transport, not to establish herds. Still, Secretary Davis was delighted with the results.

In 1857, explorer Edward Fitzgerald Beale (1822-1893) took twenty-five camels on a 1,200-mile survey from Fort Defiance, Arizona, to the Colorado River. The animals hauled heavy loads over mountains, crossed rivers, and went days without water, winning Beale’s admiration. He declared the experiment a complete success. He used camels for the construction of Beale’s Wagon Road which later became part of Highway 66 and the route for the Transcontinental Railroad. Hi Jolly served as his lead camel driver.

A second shipment brought the U.S. camel herd to about seventy camels, split between Texas and California.

Though the Camel Corps had proven camels were superb pack animals for the American Southwest – they failed to fit into U.S. military culture. Soldiers disliked their smell, bite, stubbornness, and unsettling gait. Horses panicked at their sight. Soldiers did not take too kindly being labeled “camel drivers,” and there are reports they would turn their camels loose hoping they would run away.

The Army probably would have continued to use the camels, but something occurred that totally derailed the program – the Civil War. As one historian joked, the war was the straw that broke the camel’s back. The program came to an abrupt halt in 1861 once the war was underway. The Texas herd fell into Confederate hands; the California herd stayed in Union control. Neither side made serious use of them, and after the war there was no desire to continue the program once the railroad boom was underway.

Some camels were sold to circuses and miners, others were caught in a horrible cycle of wandering, rounding up, and wandering again. Freighters cursed them for stampeding their teams. Desert well-keepers hated them for raiding feed stores. Over time, the survivors became the stuff of legend — the “Red Ghost” of Arizona and “La Fantasmas,” a camel riding skeleton along the Gila River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona.

It has been reported that in 1895 a group of camels were rounded up and sent to Chicago for an exhibition. One camel that died during a fight with another camel at Camp Tejon in California is on display at the Smithsonian Institution. This article states the camel was named Said.

The last known Camel Corps veteran, “Old Topsy,” died in 1934. Old Topsy had an interesting life. She was featured in several early films when she lived at the Selig and Griffith Park zoos. Later, she was a part of a menagerie at Ringling Brothers Circus. Find out more in this article from the National History Museum.

Major Henry C. Wayne’s strange experiment left its mark. He was awarded a gold medal by the Société Impériale Zoologique d’Acclimatation of France in 1858.

The camel driver known as “Hi Jolly” remains a folk hero in Arizona, where his grave is marked by a pyramid monument. The plaque at the monument states, “The last camp of Hi Jolly, [ birth name: Philip Tedro], born somewhere in Syria about 1828, died Quartzsite, [Arizona] December 16, 1903. Came to this country February 10, 1856. Camel driver, packer, scout over thirty years, a faithful aid to the U.S. government.” Other biographical information states he was a prospector, desert guide, and mail courier.

The camel driver known as Greek George was born Yiorgos Caralambo. He often used the named George Allen and has a bit of a notorious history. He was the alleged murderer of Alfred Bent, the son of the first territorial governor of New Mexico, in 1865. Prior to the Civil War Greek George was moving the U.S. mail out of present-day West Hollywood. After the war the U.S. government gave him a plot of land recognizing his service with the U.S. Camel Corps at the corner of present-day Santa Monica Boulevard and King’s Road where he built an adobe house. In 1874, the bandit known as Tiburcio Vasquez was captured hiding out on Greek George’s property.

Had history unfolded differently, had the U.S. Army not abandoned and neglected the camels as well as the foreign-born men they had brought over to tend to them, we might tell tales of the West being won from the backs of swaying dromedaries — and cowboy movies might have looked very different indeed.

Leave a Reply