Spend any time with Atlanta history and you can’t help but stumble over the theories regarding how Peachtree Street received its name.

A few years ago, when I was attending a museum conference, one of the younger attendees in a rather authoritative manner informed me that Peachtree Street and all the other streets that refer to the fruit were named for Peachtree Creek.

I congratulated this person on their knowledge and then asked, “Well, if the streets were all named for the creek, how did the creek get its name?”

I was met with a blank stare. How dare I question, right? What do I know? I’ve been telling people I was an old lady for the last twenty years, and with my last birthday I think I’ve officially reached the status and fully embrace it, but it is still a bit infuriating to be patted on the head and dismissed because I’m not considered relevant anymore. While the young man was in the right neighborhood, he was on the wrong street meaning he didn’t seem to know the rest of the story.

Thinking about this brings Abigail “Abi” Pittman Elder (1832-1928) to mind and her explanation regarding the naming of Peachtree Street published in The Atlanta Constitution in 1910. More about Mrs. Elder in a bit, but first if you take a stroll through the search results when conducting a Google search regarding the naming of Peachtree Street several versions of the same theories keep reappearing including recent articles and Reddit threads explaining the street was named for the creek. Ah, now I know how my young friend was so educated.

While I realize history is only valid until a new source is found, and historians do make mistakes, myself included, I tend to stand with those who have come before me such as the Eugene Mitchell, brother to Margaret Mitchell of Gone with the Wind fame, and Franklin Garret, author of Atlanta and Environs, who mentioned in his book that if we really want to know about geographic locations and the source for the names we have to go back and examine how the Native Americans named locations to get the full picture.

During the days when the Atlanta area was nothing but a wild frontier there were Indian villages located along the Chattahoochee River including the village known as Standing Peachtree. It was considered the most important village along the Chattahoochee where trade and travel were concerned not only for the Creek Nation but the Cherokee Nation across the river. It was a designated entry point for licensed white traders who wanted to trade with the natives.

Kenneth K. Krakow in his book Georgia Place Names – Their History and Origins mentions Standing Peachtree was located on both sides of the river being called PAKANAHUILI which translates from the Muskogean language to Standing Peachtree.

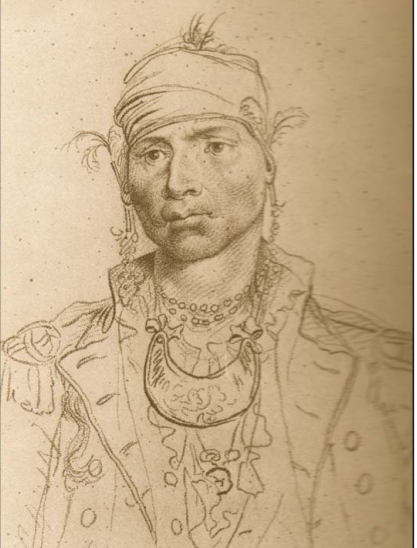

The earliest known reference to Standing Peachtree is found in a letter dated May 27, 1782, written by Jonathan Martin discussing a rendezvous that would take place the next day between “Mr. McIntosh with a strong party of the Cowetas and Tallasee King” at Standing Peachtree. McIntosh, of course, refers to William McIntosh, Sr. (1745-1794), a Scottish American soldier. He was loyal to the Crown during the American Revolution and worked to recruit the Creeks as British allies. He was also father to William McIntosh, Jr. (1775-1825), the Creek leader, who was assassinated after signing the Treaty of Indian Springs (1825). Tallasee King of the Creeks (about 1755-about 1820) was also known as Hopothle Mico, a Creek leader. This drawing was completed by John Trumbull when Hopothle Mico visited with President George Washington in 1790.

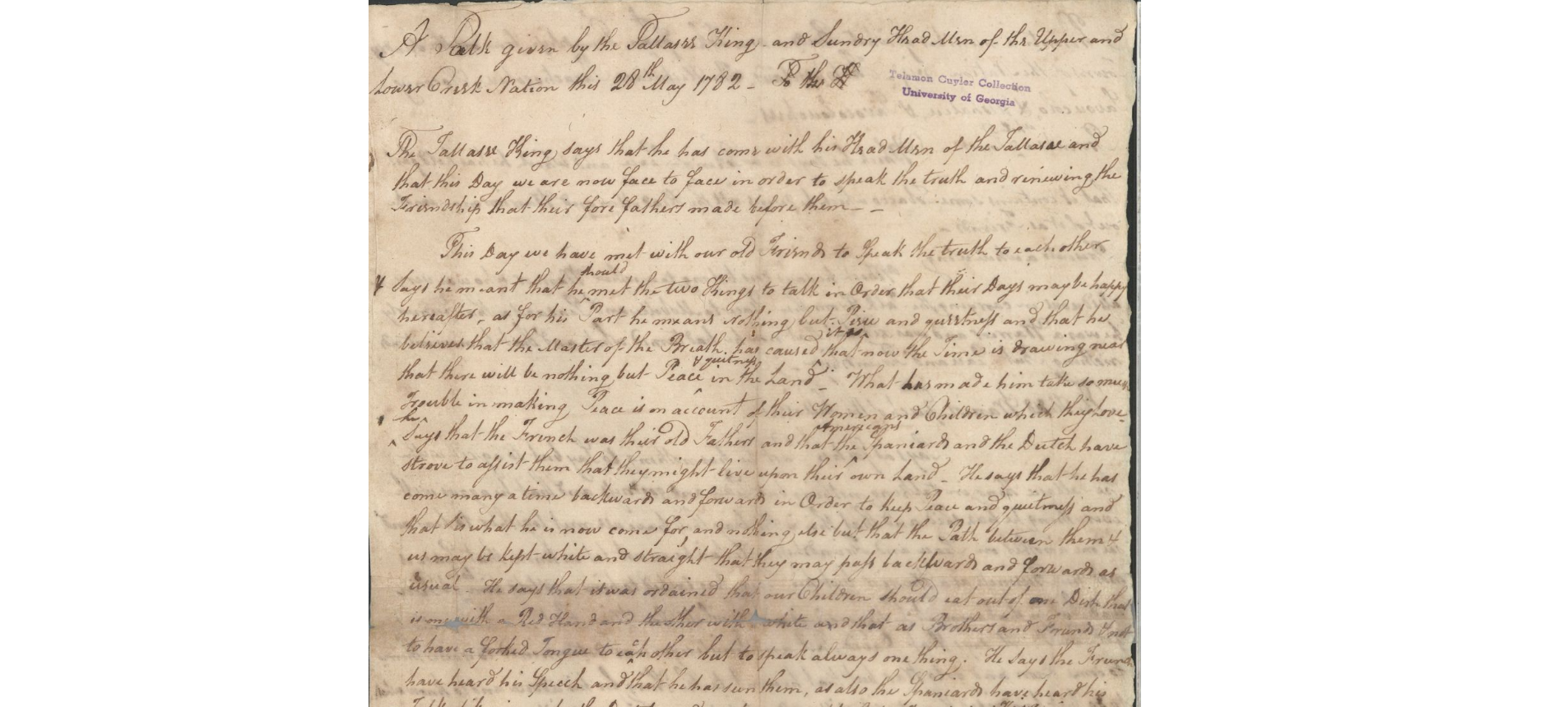

Below is an image showing part of the remarks Tallasee King made during the rendezvous at Standing Peachtree.

You can see a complete copy of Tallasee King’s remarks here.

Another early reference to Standing Peachtree is from a set of Executive Council Minutes dated August 1, 1782, that mentions a commissioner had been sent to Standing Peachtree to meet with Native Americans for treaty purposes.

These two early references indicate that even before white men settled at what would become Atlanta, the word “peachtree” was already part of a geographic name used by both Native Americans and early settlers and traders, but why name the village after a tree that wasn’t growing in the area in great abundance?

Native Americans were known to name their towns and villages after something physical – a tree, a river, an animal. For example, the Native American name for the area that would become the city of Douglasville was named for a very tall Skint Chestnut tree that stood high on the Tallapoosa Ridge. Even today the Douglasville city emblem has a tree in the middle of it to represent the Skint Chestnut harkening back to when it is said Native Americans used the tree as a location marker. Early pioneers used the marker as well to make sure they were on the right trail heading west.

Though we had early sources mentioning Standing Peachtree by name as early as the 1780s, the history became a bit confused when Eugene Mitchell wrote an article for the Atlanta Historical Bulletin in January 1928 titled ‘The Story of Standing Peachtree.’ I encourage you to click through when you have time to read the entire article by Eugene Mitchell as it provides more sources than I relate here.

In Mitchell’s article “Miss Virginia Harden, whose grandfather was the first clerk of the Superior Court at McDonough in Henry County and served as a soldier at Fort Peachtree (more about the fort below), said that her grandfather stated that it was his understanding that the name came from a pitch/pine tree.” Another man, Thomas H. Jeffries, a former Fulton County Ordinary, told Mitchell that Hiram Casey, one the earliest settlers in the Atlanta area, said the name came from a pitch/pine tree.

It is interesting to note that no mention of the pitch/pine tree version of the story exists before the 20th century. It’s important to note that someone else told Virginia Harden and Thomas H. Jeffries about the pitch/pine tree, and in both cases the other person was deceased and could not be reached for verification. In a court of law this would be called hearsay.

I call these types of sources “mama saids.”

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve interviewed someone and ended up with a bunch of bunk where absolutely nothing could be substantiated in any way. Most of the time they begin with “My mama said…” Many times, the “mama saids” are not true. They are misleading at best. Most don’t mean to lie, and I’m not saying the two sources Mitchell spoke with were lying, but when people are interviewed, they want to be included or quoted so much that they often say anything including repeating recollections that might not be factual. A fellow historian friend once advised, “Tell these people their mama wasn’t lying, but whoever shared the information with mama most certainly lied!”

Eugene Mitchell does quote an original source in his 1928 article – George Washington “Wash” Collier (1813-1903) – from an interview Collier gave that was published in The Atlanta Constitution on April 25, 1897. Collier was living in DeKalb County around 1823 and by the 1830s was carrying the mail between Decatur and Allatoona, Georgia. The route took him past Standing Peachtree which was then a post office stop (closed by 1842) where James McConnell Montgomery (1768-1842) was the postmaster.

Collier also stated that Standing Peachtree took its name from a lone peach tree which grew on a high mound at the confluence of a creek (now known as Peachtree Creek) and the Chattahoochee River. The lone peach tree Collier said he saw fits with the mentions of the Indian village in the late 1700s and with the native practice regarding naming geographic locations.

During the War of 1812 several forts were built throughout Georgia’s frontier for protection. The site of Standing Peachtree became one of those forts at that time completed in 1814 and manned by the James McConnell Montgomery already mentioned. You can find out more about Fort Peachtree at this link. A replica of the fort can be visited by appointment at 2630 Ridgewood Road, N.W.

A year before another fort had been completed at Hog Mountain in Gwinnett County (originally Jackson County) known as Fort Daniel. Franklin Garrett surmises these forts had to be connected by some form of road – the original Peachtree Road which follows an ancient Indian trial as most of the older roads do.

The pitch/pine tree simply falls apart upon examination though as Mr. Garrett states in his book, Atlanta and Environs, the story is logical since you can’t go very far in Georgia without bumping into a pine tree while peach trees aren’t commonly seen growing wild.

However, once peach trees were brought in by settlers and planted, they generally thrived. Since Standing Peachtree had been a gateway for white traders, isn’t it possible they brought in a peach tree and it was planted at some point on the mound that George Washington Collier stated he saw?

The road that had to exist between Fort Peachtree and Fort Daniel is where the lady I mentioned above, Abi Pittman Elder, comes into my research. In 1910, she wrote a letter to the editor of The Atlanta Constitution and said:

I wish to tell you what I know to be the facts as to the naming of Peachtree Street. I was born on Peachtree Road, in 1832, a few miles above Norcross, near Pinkeyville, which was at that time an Indian trading post, kept by one Mr. Gates, and I remember asking my father, Daniel N. Pittman, why the road was called Peachtree. He said that when the first settlers came from North and South Carolina they brought fruit trees and peach seed, and planted them, peaches being a quick growth. The pioneers settled near each other for protection from Indians. In a few years the trees began to bloom, and in the spring, there was almost a continuous row of blooming orchards from Pinkeyville to Gainesville and Clarksville, on to Greenville, South Carolina. When Atlanta came on of course Peachtree Road led to it, and in the city was called Peachtree Street. “Historical collections of Georgia” speaks of the lone Peachtree at one of the crossings of the Chattahoochee River, and also says of DeKalb County the principal creeks are Nancy, Utoy, and Peachtree.

It could be argued Mrs. Elder’s recollection saying her father told her about the peach trees being brought by early settlers is hearsay, a “mama said” as I argue, but Mrs. Elder also saw evidence of the peach orchards herself. She knew the trees were along the road.

The Historical Collections of Georgia Mrs. Elder refers to is the 1854 publication by George White (1802-1887) formally known as Historical Collections of Georgia Containing the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, etc. Relating to Its History and Antiquities, From Its First Settlement to the Present Time. Folks loved long flowing titles back then. Today, most people like me simply refer to the book as “White’s.”

Mrs. Elder’s father, Daniel N. Pittman was living in Gwinnett County in its earliest days. In 1834, the state legislature appointed him to establish a ferry across the Chattahoochee River on his land which was situated between the current towns of Duluth and Norcross. Later, the Pittman family moved to Atlanta. Mrs. Elder’s brother – Daniel J. Pittman – was the Fulton County Ordinary between 1863 and 1887. Mrs. Elder was married to Williamson D. Radford “Rad” Elder from old Campbell County. He was blinded at Chickamauga in 1863 and lived out the remainder of his life supporting his family on a Confederate pension and working as a street peddler at Palmetto. Both he and Mrs. Elder are buried at the Fairburn City Cemetery.

As you can tell, I don’t support the pitch/pine tree story regarding Standing Peachtree at all. We have more first-hand sources that a lone peach tree grew at the confluence of the creek that would become Peachtree Creek and the Chattahoochee River, but what does Mrs. Elder and I know? We are just a couple of old ladies.

Believe as you wish.

Look for another column regarding Mrs. Elder’s recollections soon!

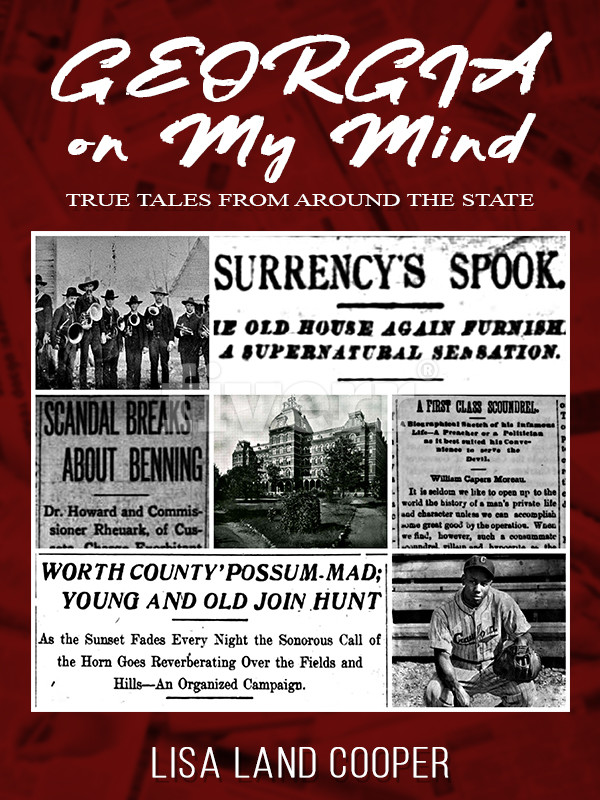

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my latest book – Georgia on My Mind: True Tales from Around the State – which contains 30 true tales from all around the state including three stories from Atlanta, and yes, there will be volume two out soon! You can purchase the book here…in print and Kindle versions.

Leave a Reply