A few years ago, I was honored to visit the city of Augusta, Georgia as a board member for the Douglas County Museum of Art. I was an attendee of the annual conference for the Georgia Association of Museums and Galleries. Between meetings and presentations, I did many things tourists do while in Augusta including visiting the Augusta Museum of History, the Morris Museum of Art, and the boyhood home of President Woodrow Wilson.

Another place I visited was Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church at Reynolds and Sixth Streets.

I walked through the graveyard there where William Few, Jr. (1748-1828), signer of the U.S. Constitution, is buried along with George Mathews (1739-1812), a former Georgia governor. Patriots of the American Revolution, who died during the Siege of Augusta (1781), are said to have been buried in this churchyard, near where they fell. Some are supposed to lie beneath the walk which leads to the church.

It was a quiet day. As I walked among the headstones, I occasionally heard the soft rustle of oak leaves and the occasional toll of a distant bell, but if history had a sound there at that spot beside the Savannah River, it would whistle.

That’s because the site of St. Paul’s is no ordinary patch of land. In its soil are the echoes of three revolutionary American sounds: the whistle of the first steamboat, the hiss of the first cotton gin, and the roar of one of the earliest locomotives.

It was from this ground that some of the greatest forces in nineteenth-century commerce were launched.

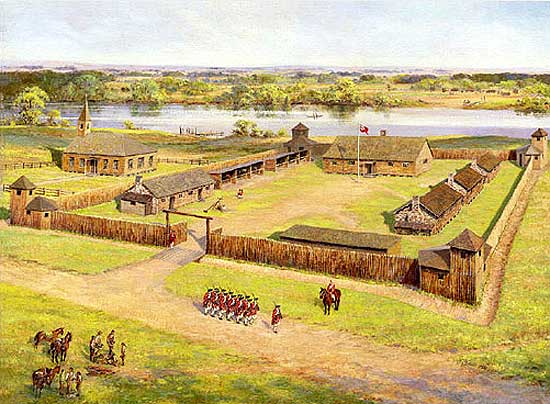

Before Augusta was a city, it was a frontier outpost. In 1735, General James Oglethorpe built Fort Augusta to protect traders and settlers on the land where St. Paul’s is located today. By 1750, the first St. Paul’s Church was built “under the curtain of the fort.” The fort was active through 1767 serving as a place where General Oglethorpe met with Native American leaders. In 1763, chiefs of the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Catawba, and Chickasaw nations, colonial governors from Georgia, North and South Carolina, Virginia, and a representative of the King to sign a peace treaty. This was also the spot where in 1773, Cherokees and Creeds ceded two million acres in North Georgia.

During the American Revolution the British controlled Augusta and erected their own fort at the St. Paul’s site calling it Fort Cornwallis only to lose it twice—first in 1780 when Americans surprised the garrison, and again in 1781 after a dramatic siege led by General Andrew Pickens and “Lighthorse Harry” Lee. They even used a Mayham tower—basically a wooden sniper’s nest on wheels—to help force the British surrender on June 5, 1781.

The Revolution left Georgia broke but not broken. In its wake came dreams of industry, invention, and independence. In the next few years after the Patriots reclaimed Fort Cornwallis from the British, a new era of invention took root.

It began with a latch string.

After the war, Georgia thanked General Nathanael Greene for his service with a plantation: Mulberry Grove, on the Savannah River. When he died, his widow, Catherine Greene, remained there—and it was her open-door hospitality that changed history.

One day, a young, unemployed New Englander named Eli Whitney (1765-1825) tugged on her “latch string.” With no job but plenty of mechanical curiosity, Whitney was encouraged by Mrs. Greene to try designing a machine that could clean the seeds from short-staple cotton. He wasn’t the first to dream it up—Joseph Eve, a Loyalist’s son from Pennsylvania, had invented a roller gin in the Bahamas years earlier and brought his designs to Augusta. But Whitney’s saw gin was different—it could handle the hearty cotton that thrived in Georgia’s soil.

On Rocky Creek, a few miles from Augusta, is the place where, in 1796, Eli Whitney erected and put into operation the first cotton gin launching what would become the Deep South’s most powerful economic engine.

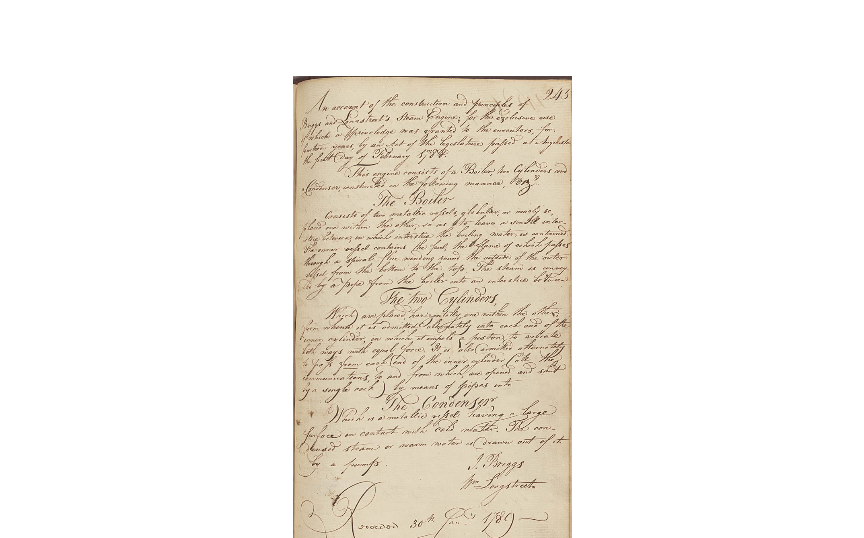

While Eli Whitney was revolutionizing agriculture, William Longstreet (1759-1814), a New Jersey transplant and self-taught inventor, was staring down the Savannah River with dreams of steam-powered boats. It’s interesting to note that Longstreet along with Isaac Briggs (1763-1825), an engineer and surveyor, received the very first patent for applying steam to navigation on February 1, 1788. Not only was the patent the first regarding steam and navigation issued in the United States, it was also the first patent issued by the Georgia Legislature. At that time state legislatures issued patents because the U.S. government was still operating under the Articles of Confederation and did not have patent powers. The first U.S. patent would not be granted until 1790. Longstreet did receive a U.S. patent on October 9, 1802 (Patent Number 401X), but by the time he launched his steamboat, it had expired.

Briggs evaporates from the steamship story rather quickly. He later assisted Andrew Ellicott surveying the boundaries of the original District of Columbia, and in 1803 he was appointed Surveyor General by President Thomas Jefferson for the Mississippi Territory.

The mention seen below was placed by Longstreet and Briggs in the Georgia State Gazette from April 5, 1788. It mentions they had discovered “a new mode of applying steam to machinery” and gave notice of their patent.

The Georgia patent gave Longstreet and Briggs the “exclusive patent rights for a term of fourteen years to a steam engine for the purposes of navigation.”

Many words can be used to describe Longstreet. My favorite is persistent.

During a twenty-year period, Longstreet became a familiar figure on the Savannah River conducting his experiments using steam. With no foundries, machinery, or investors, he worked at building an entire steamboat from local pine trees using a handmade steam engine.

As you might guess, he became the focus of ridicule as most inventors do at some point. People laughed. They even made up a song to mock him with the lyrics:

Can you row the boat ashore, Billy Boy, Billy Boy?

Can you row the boat ashore, Gentle boy?

Can you row the boat ashore without a paddle or an oar, Billy Boy?

Even the state legislature seemed to scoff at Longstreet’s idea. The page in the dusty old book where the original patent is recorded says, “Briggs and Longstreet: Steam Nothing, 245.”

Longstreet acknowledged the ridicule he faced in a letter he wrote to then Governor Thomas Telfair dated September 26, 1790, which also can be found at the Georgia Archives saying, “I make no doubt you have often heard of my steam engine and as often heard it laughed at.” Longstreet’s letter was a request for Governor Telfair’s assistance and patronage, but there is no record if Telfair assisted Longstreet in any way.

Longstreet gave an update on his progress with the steam engine in the Augusta Chronicle, in 1792.

While he continued to work on his steam method for navigation, Longstreet tinkered with other inventions including an improvement to Whitney’s cotton gin. He received a patent for the “breast roller.” He set up two gins at Augusta and another two at St. Marys, but both of those were destroyed by the British during the War of 1812.

Longstreet also patented a steam sawmill. This invention was mentioned in the Columbian Museum and Savannah Advertiser in 1802.

Finally on August 19, 1807 the citizens of Augusta gathered on the banks of the Savannah River to watch Longstreet launch his steamboat. It was built of wood, fueled by faith, and powered by sheer will.

The people jeered and sang the song mocking his boat with no paddles or oars, but when his wooden steamboat glided through the water, powered by steam alone, laughter turned to stunned silence.

After the initial success Longstreet continued to tinker with and improve his steam boat. Many accounts say he was ready to request a federal patent when news came of Fulton’s success with the Clermont on the Hudson River on August 17, 1807 two days before Longstreet’s launch.

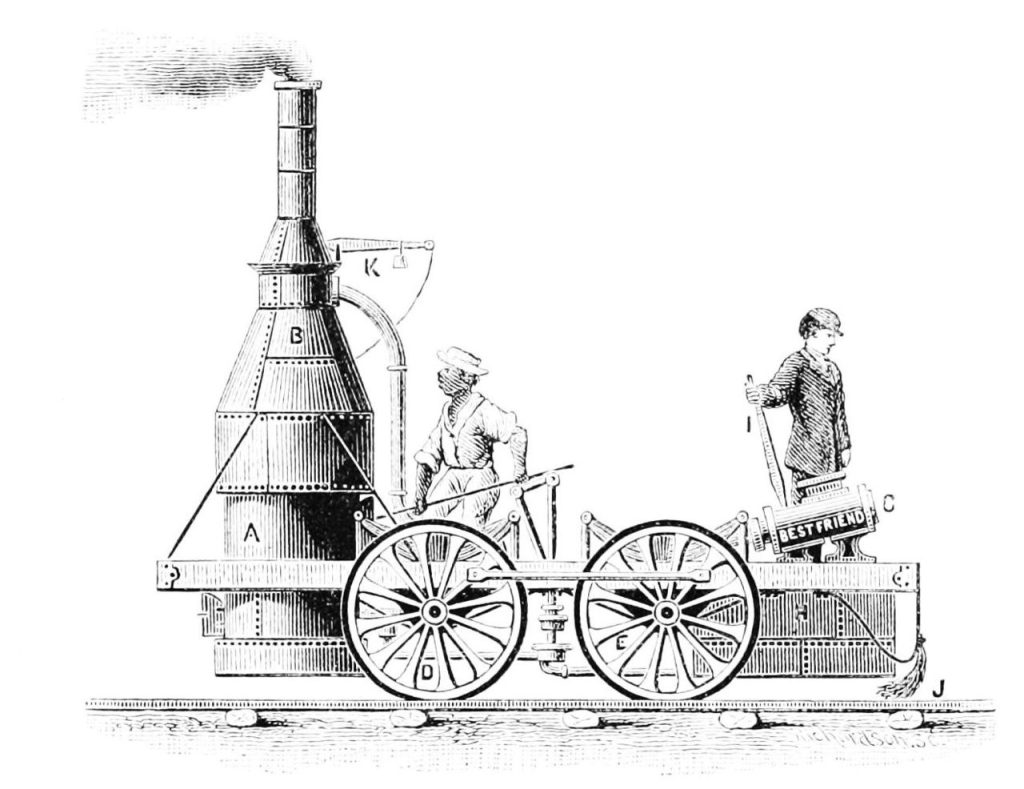

Just across the river in Hamburg, South Carolina, the next revolution rolled in—literally. In 1830, the Charleston-to-Hamburg railroad became the longest in the world and featured America’s first domestically built locomotive, the Best Friend. During its early runs, the train terrified crowds, including one that panicked when the steam hissed too loudly, causing a platform collapse and multiple casualties.

The trains were so new, they were outfitted with sails—just in case the steam failed.

The Best Friend was the first American-built locomotive in regular continuous service. It operated from January to June 1831, when it was destroyed by a boiler explosion that occurred when the locomotive’s fireman sat on the safety.

From the banks of the Savannah at St. Paul’s, three whistles once rang out—one from a steamboat, one from a cotton gin, and one from a locomotive. Each marked a turning point. Each changed the pace, power, and prosperity of the South.

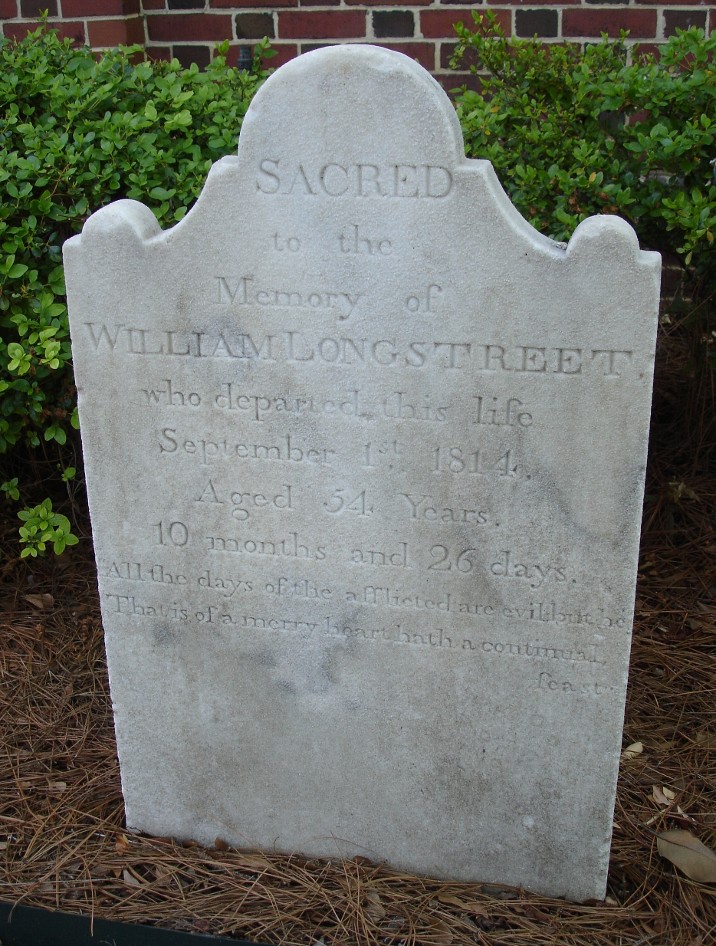

Oh, and William Longstreet? Though his inventions never made him rich, his joy came from proving what others said couldn’t be done. He died in Augusta and is buried in the churchyard at Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church – another unsung genius whose echoes still whistle through history.

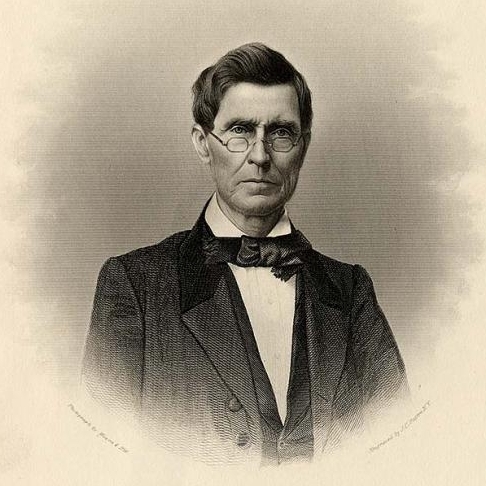

William Longstreet’s son, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet (1790-1870), born in the same year his father sent his letter to Governor Telfair, would carry on the family’s legacy – not as an inventor, but as humorist and Southern storyteller publishing the book Georgia Scenes as well as serving as the president of the University of Mississippi, Emory College, now known as Emory University, and South Carolina College, now known as the University of South Carolina.

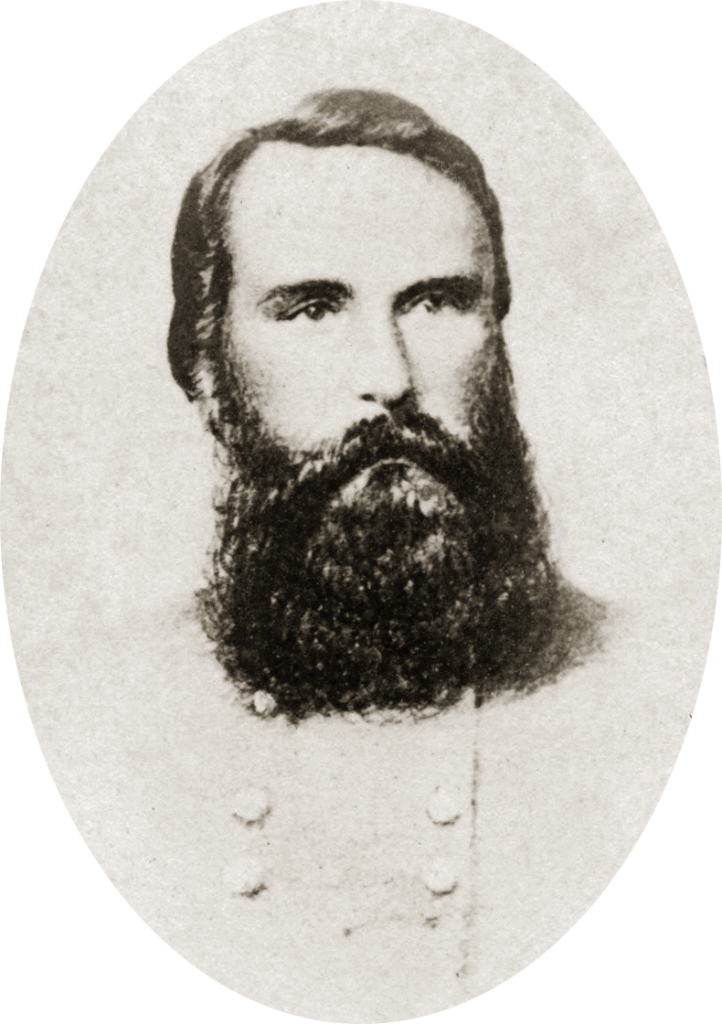

William Longstreet’s grandson was the Confederate General James Longstreet (1821-1904). General Robert E. Lee called General Longstreet his “Old War Horse” due to his loyal and consistent service.

Today, the site of St. Paul’s in Augusta whispers stories beneath its modern pews. Beneath it once stood forts, hosted treaty councils, housed cotton gins, and launched steam engines.

If you listen closely, you might still hear three whistles:

The first, calling colonists to independence.

The second, summoning cotton into kinghood.

And the third—ah, the third!—a whistle of steam, stubbornness, and one man’s refusal to believe that genius required permission.

Leave a Reply