I came across an article the other day regarding the pistols that were used during the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr on July 11, 1804. At the time of the duel Hamilton was the first and former Secretary of the Treasury having served in President George Washington’s administration, and Burr was the sitting Vice President of the United States.

The duel took place in Weehawken, New Jersey. Though it was illegal in 1804 dueling was a common practice between men wishing to defend their honor. Hamilton had been involved in twelve different duels dating back to 1779 and there are reports that Burr and Hamilton had met at least once before that fateful day in 1804. Hamilton’s son, Philip, had been killed in a duel near the same spot where Hamilton would be mortally wounded.

Hamilton and Burr had had political and U.S. policy disagreements for many years and things escalated in 1791 when Burr won his Senate seat from Hamilton’s father-in-law, Philip Schuyler. This led to Hamilton doing what he could to keep Burr from becoming U.S. President during the Election of 1800 when the Electoral College was deadlocked. Burr was the runner-up to Thomas Jefferson, so according to the rules of that time, he became Jefferson’s vice president.

Jefferson never trusted Burr and often excluded him from party matters, but as President of the Senate there are many accounts that state Burr handled the position masterfully. When President Jefferson decided to drop Burr from his ticket for the 1804 election, Burr ran for governor in New York instead. Once again Hamilton did what he could to make sure Burr would lose the election.

Hamilton managed to get one shot fired during the duel which missed Burr entirely while Burr’s hit Hamilton above his right hip damaging his spleen and liver. He was taken to the home of William Bayard, Jr. in the Greenwich Village section of New York and died the next day.

As the coroner’s jury convened two days after Hamilton’s death Burr packed his bags and first went to Pennsylvania and then fled to Georgia where he hoped he still had a few friends. As most things are in the historical record some claims regarding events are dubious while others are true, so I thumbed through a few books on my shelf to see what historians have said through the years regarding Burr’s trip to Georgia.

In the book Aaron Burr: Portrait of an Ambitious Man (1967) by H.S. Pamet and M.B. Hect I read “…after the duel, [Burr] immediately completed plans which he had already initiated to go to St. Simons, an island off the coast of Georgia.”

I found, “Burr visited St. Simons while fleeing form the ghost of Hamilton whom he killed in a duel,” in the book This is Your Georgia (1986) by Bernice McCullar.

From the book Ordeal of Ambition: Jefferson, Hamilton, Burr (1970) by Jonathan Daniels I read that Burr secretly embarked for Georgia and there on St. Simons Island at the Hampton Plantation of his friend, rich former Senator Pierce Butler, he found refuge…”

Burr reached the Georgia coast in mid-August. Pierce Butler’s plantation was on the northern end of St. Simons Island. The two men had become friends while serving together in the U.S. Senate.

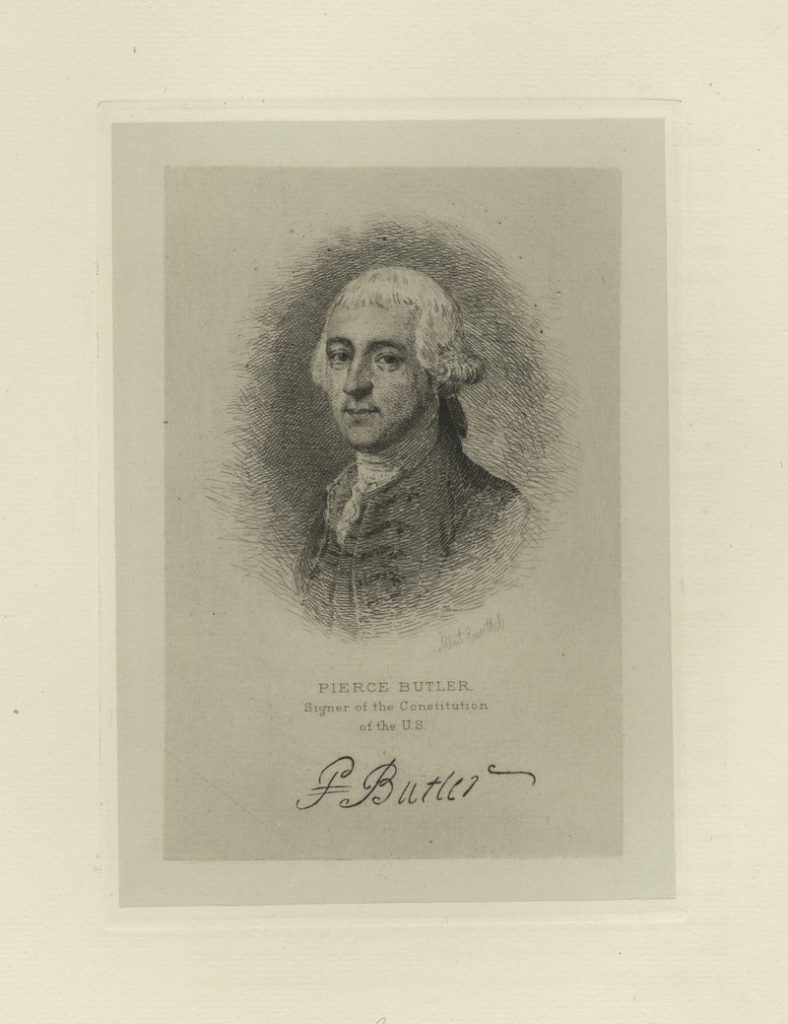

Pierce Butler (1744-1822) was born the third son of an Irish baronet. He came to the American colonies as a soldier, married a South Carolina plantation owner’s daughter, and sided with the Patriots during the American Revolution. Butler was one of the signatories on the U.S. Constitution in 1787, and he and Aaron Burr served together in the U.S. Senate through most of the 1790s.

Butler had purchased Hampton Point on St. Simons Island in 1774. By the time Aaron Burr reached Butler’s property in mid-August 1804 it was the island’s largest cotton plantation in acreage and slaves. You might remember that it was Pierce Butler’s grandson by the same name who married the British actress, Fanny Kemble, in 1830. She published a book that shed light on the ills of slavery that became front and center during the days leading up the Civil War.

It is through the letters that survive to this day between Burr and his daughter, Theodosia “Theo” Burr Alston (1783-1813) that we can trace his movements while he was in Georgia. Theo Burr was highly educated beyond the normal French, music, needlepoint, and dancing instruction most women of her station were given. Burr made sure his daughter was educated in arithmetic, Greek, Latin, and English composition, too. Their correspondence spans Theo’s schooldays through her death and number in the thousands.

So accomplished was Theo that her father entrusted her to be his social hostess for important dignitaries even when he was not at their Manhattan Island home, Richmond Hill.

In 1801, Theo Burr married Joseph Alston from South Carolina. It is interesting to note that the couple was the first recorded newlyweds to spend their honeymoon at Niagara Falls. After the birth of her son in 1802, Theo’s health would remain fragile, but she firmly stood by her father through all his troubles.

In a letter to his daughter Burr’s used a bit of sardonic humor regarding his situation when he wrote:

“There is a contention of a singular nature between the two states of New York and New Jersey. The subject in the dispute is, which shall have the honor of hanging the Vice President. You shall have due notice of time and place. Whenever it may be, you may rely on a great concourse of company, much gayety, and many rare sights.”

Burr also described Hampton Plantation writing it “affords plenty of milk, cream abundance, figs, peaches, melons, oranges, and pomegranates,” but he hated the oppressive heat and the swamps.

Burr did not sign his letters identifying himself as Theo’s father or in any way as Aaron Burr. He used the name R. King or Roswell King. Some historians state Burr not only used the name in correspondence but while he was traveling, too. From Butler’s plantation he could travel to other Georgia islands or make forays into Florida.

The name Roswell King wasn’t a manufactured alias but represented a real person. During the time Burr was a visitor at Butler’s plantation, Roswell King (1765-1844) was Butler’s overseer and would have been known to Aaron Burr. During the 1830s King would move north to the area along Vickery Creek that would become the town named for him today, Roswell, Georgia.

In a letter dated September 3, 1804 Burr discussed the village and fort known as Frederica on St. Simons Island saying:

In the vicinity of the town several ruins were pointed out to me, as having been, formerly, country seats of the governor, and officers of the garrison, and gentlemen of the town. At present, nothing can be more gloomy than what was once called Frederica. The few families now remaining, or rather residing there, for they are all new-comers, have a sickly, melancholy appearance, well-assorted with the ruins which surround them. The southern part of this island abounds with fetid swamps, which must render it very unhealthy. On the northern half, I have seen no stagnant water.

The fort was built by General James Oglethorpe between 1736 and 1748 to protect the southern boundary of colonial Georgia from Spanish raids and played an important role in the Battle of Bloody Marsh in 1742. By 1749, the fort had fell into disuse and the little village that had sprung up around declined as well.

While using Pierce Butler’s home as his base through September Burr’s letters to his daughter describe excursions to nearby Darien and Little St. Simons Island. He also visited his friend John Couper at Couper’s Point plantation located on the northeast portion of St. Simon’s Island.

The namesake for Cannon’s Point is Daniel Cannon, the carpenter for General James Oglethorpe, who settled there. John Couper, a Scotsman who came to American at the young age of sixteen as an apprentice, purchased the land in 1793 and built a very successful plantation. Couper is remembered as an agricultural innovator experimenting with many things including citrus and olive trees as well as date palms.

More can be discovered about the Couper family at this link that includes photos of Couper and his wife and a painting of the home. This book titled The John Couper Family at Cannon’s Point (1994) by T. Reed Ferguson is interesting, too.

Today, the Couper property is known as Cannon’s Point National Preserve.

Burr arrived at the Couper home just in time to experience the Antigua-Charleston Hurricane of 1804 which hit the Georgia coast making landfall on September 7, 1804. Burr rode the hurricane out in Couper’s three-story mansion.

In a September 12th letter, Burr recalled:

In the morning, the wind was still higher. It continued to rise, and by noon blew a gale from the north, which, together with the swelling of the water, became alarming. From twelve to three, several of the out-houses had been destroyed; most of the trees about the house were blown down. The house in which we were shook and rocked so much that Mr. Couper. began to express his apprehensions for our safety. Before three, part of the piazza was carried away; two or three of the windows bursted in. The house was inundated with water, and presently one of the chimneys fell. Mr. Couper then commanded a retreat to a storehouse about fifty yards off, and we decamped, men, women, and children.

You may imagine, in this scene of confusion and dismay, a good many incidents to amuse one if one had dared to be amused in a moment of much anxiety. The house, however, did not blow down. The storm continued till four, and then very suddenly abated, and in ten minutes it was almost a calm. I seized the moment to return home.

“Home” refers to Burr’s return to the Butler home at Hampton Plantation.

The Antigua-Charleston hurricane was the most severe storm to hit Georgia since 1752, causing 500 deaths and at least $1.6 million dollars (1804 USD) in damage across the region including ruining cotton, rice, and corn crops.

James T. Vocelle in History of Camden County (1967) states Burr spent the night with Major Archibald Clark and his wife, Rhoda Wadsworth Clark at their home which still stands in St. Marys at 314 Osborne Street, but no exact day is given. Clark was a lawyer and he and Burr had attended the same law school but ten years apart. Clark had been appointed by President Thomas Jefferson as a U.S. Customs Agent, collecting taxes from ships.

It’s interesting to note that Brian Brown who produces the fabulous website Vanishing Georgia advises there is “no mention in either Aaron Burr’s or Major Clark’s records that indicate Burr was at St. Marys.” Family members lived in the Clark home for decades and passed the story along to each generation stating that Burr did indeed stay in the home over night.

Today, the Clark home, or more formally the Jackson-Clark-Bessent-Madonnell-Nesbitt House, is the oldest residence in St. Marys. During the War of 1812 British soldiers arrested Major Clark and established temporary headquarters in the home. General Winfield Scott also stayed in the home on his way to the Indian Wars in Florida.

Today, the home is known as The Federal Quarters and is open for visitors needing a place to stay. The owners advertise that you can rest your head in the same room where Aaron Burr stayed during his visit to the Clark home.

Burr’s original plans for his “southern tour” was to head further south into Spanish Florida but the hurricane changed this. He did make it to Dungeness on Cumberland Island, home to Revolutionary War Major-General Nathanial Greene’s widow. The Greene family had acquired 11,000 acres on the island as payment of a debt owed to Major-General Greene (1742-1786) in 1783.

Greene had been one of George Washington’s most talented and dependable officers especially in the southern theater of the war. He died in 1786 at Mulberry Grove in Chatham County, Georgia which was another plantation belonging to Greene that had come to him as payment for his service to the new nation during the Revolutionary War. You might remember from your own study of Georgia history that Mulberry Grove was the location where Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin.

Greene’s widow, Catherine “Caty” Littlefield Greene Miller (1755-1814) would remarry choosing her children’s tutor, Phineas Miller, as her second husband. The marriage took place in 1796 at the Philadelphia home of George Washington during his term as President of the United States.

At some point the Millers sold Mulberry Grove and elected to live at Dungeness building a four-story tabby mansion there in 1800. Caty Miller was an incredibly strong woman. During the Revolutionary War she followed Major-General Greene from encampment to encampment including Valley Forge where she remained during the hard winter of 1777 and on into 1778.

Caty Miller and her first husband had been friends of Alexander Hamilton. When she heard Aaron Burr was nearby and might visit, she and her family left their home leaving their servants to greet the Vice President of the United States. There was no mistake in the message this sent. It was a major social snub.

Dungeness was taken over by the British during the War of 1812. The property had been abandoned by the Civil War and burned in 1866. Years later Andrew Carnegie, brother to Thomas M. Carnegie built a mansion on the same site. It was destroyed by fire in 1925 and the ruins of the great home remain. The Carnegie version of Dungeness is the one most people think of today when the name “Dungeness” comes up in conversation.

Some sources state that Burr also reached Fort George Island on September 15, 1804, located in Florida near the mouth of the St. John’s River. There he spent ten days with John Houston McIntosh (1773-1836). The McIntosh property is now home to the Kings Bay Naval Submarine Base today. Just one year prior to Burr’s visit McIntosh had purchased the land on Fort George Island and took an oath to the Spanish Crown and was then deemed a “colonial subject of Spanish Florida” though he owned land in Georgia including his plantation called Refuge along the Satilla River in Camden County. In the 1820s he would build the McIntosh Sugar Works near St Marys Georgia.

Burr ended up returning to Washington, D.C. late in the year and finished his term as vice president. He served as the presiding officer during the impeachment trial of Associate Justice Samuel Chase of the Supreme Court in 1805, the only member of the Supreme Court to face impeachment. By this time Aaron Burr had pending murder charges against him in both New York and New Jersey regarding Alexander Hamilton’s death. Chase would be acquitted on March 1, 1805 and Burr would give his farewell speech to the U.S. Senate the following day. It is said that many in the chamber had tears in their eyes as Burr spoke.

Burr’s charges in New Jersey melted away when the New Jersey Superior Court quashed them. The New York murder change never went to court either, but Burr was convicted on a misdemeanor charge regarding dueling in New York. This meant he could not vote, practice law, or hold public office for twenty years.

Click this link to move on to part two of Burr’s Sojourn in Georgia. This time he travels through western and middle Georgia under federal charges of treason.

Leave a Reply