One of the best-known movers and shakers in Atlanta in the years leading up to the Civil War was Marcus A. Bell – the A stood for Aurelius, a nod to Marcus Aurelius of ancient Rome fame. In fact, Bell was born in 1828 in Elbert County, and his parents named some of their children for men of ancient Rome including Jedediah Flavius, Lycurgus Mucklesworth, and Margenius Assyrumus Bell.

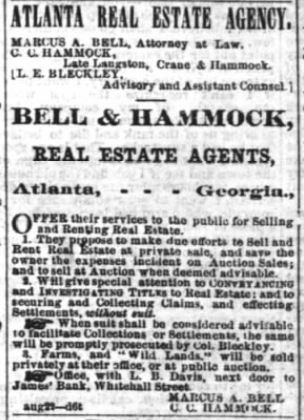

Marcus A. Bell was an attorney, but his principal profession was real estate dealer.

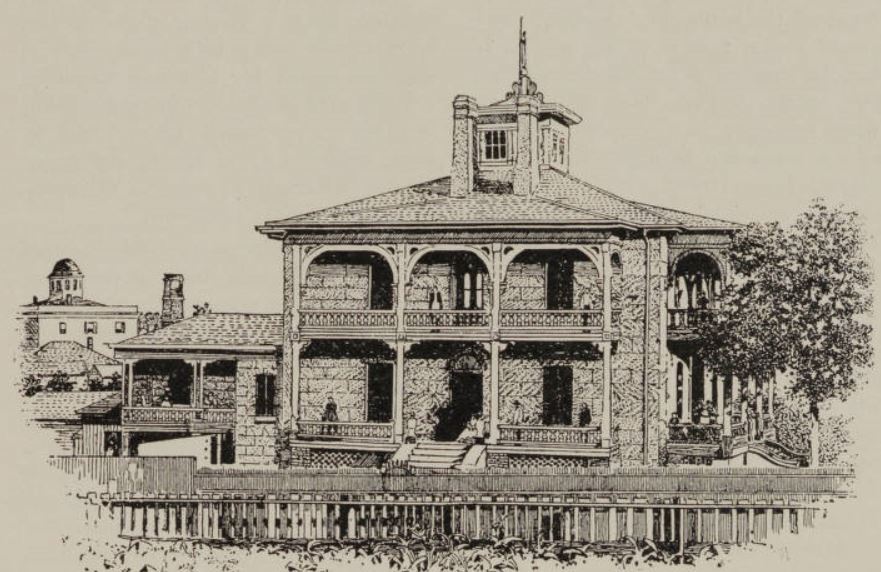

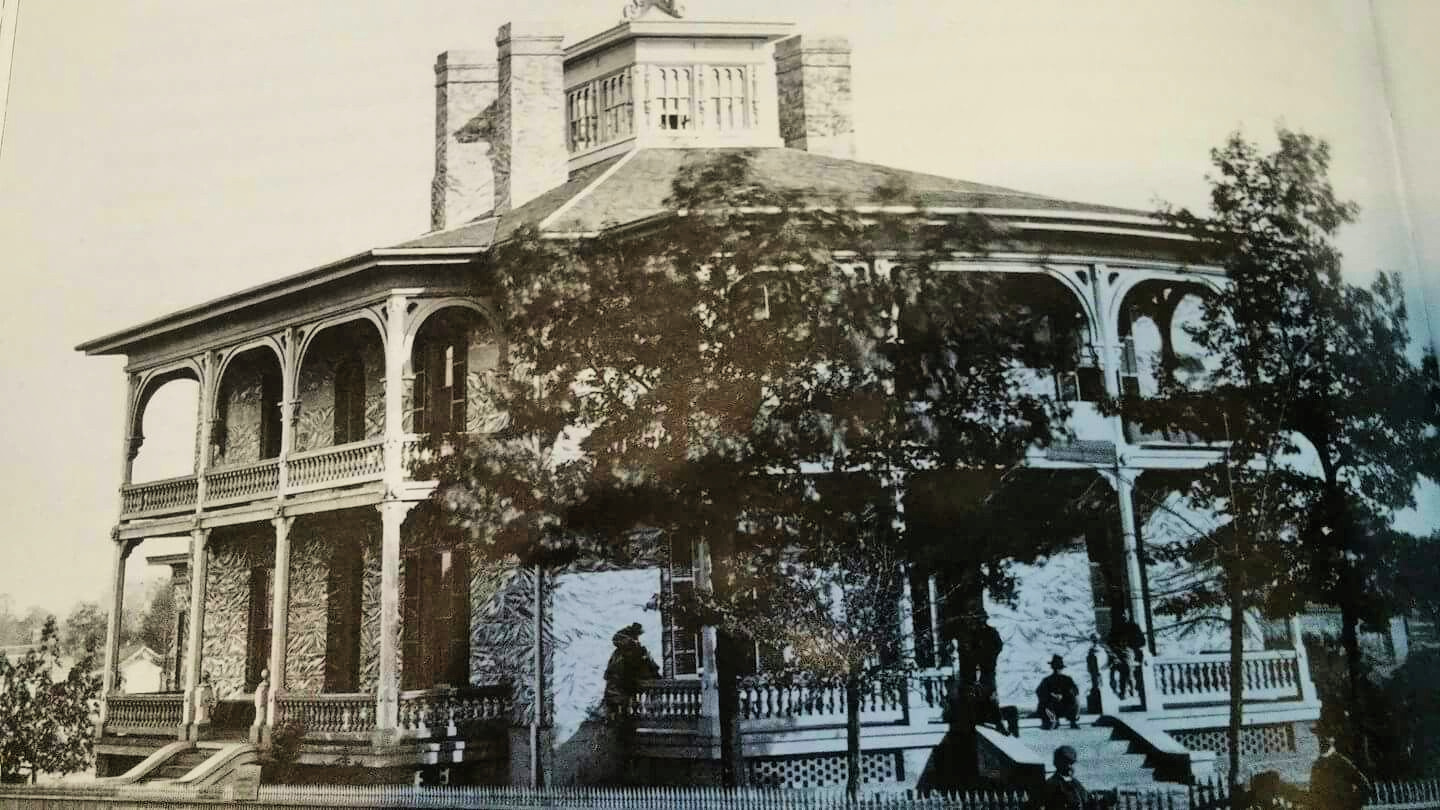

In 1859, Bell began construction of a new home for his family at the corner of Wheat and Collins Streets now known as Auburn Avenue and Courtland Street. The property included almost the entire block and measured 4 full acres. The home was finished around the time the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter at a cost of $6,000.

May and Corput designed the Bell home while Thomas G.W. Crusselle, assisted by his brother-in-law, Franklin P. Rice, were the contractors. Mr. Rice’s son, named for his father, went on to be an Atlanta city councilman and served a few terms in the legislature, but he could remember as a young man assisting in carrying brick and mortar to the home’s topmost heights.

Most believed the home was the most compactly built in the city of Atlanta. There were three floors sustained by massive stone walls, four feet in thickness at their base. They narrowed a little as they rose to the roof rafters that sustained a heavy slate roof.

The stone used for the walls was described as hard bluish “whin” rock hauled from what was known at the time of its erection as Lynch’s quarry, just outside of the western part of the city. The quarry was owned by Patrick Lynch, and today many know it as Bellwood Quarry soon to be a city park.

The Bell home would be the second home in the city crowned with an observatory or cupola. The other home was the Leyden home built by Major J.A. Leyden, also a prominent gentleman in the city. Leyden and Bell had noticed the unique feature when Dr. J.W. Tucker was building his home on his property bounded by Washington, Crew, Clarke, and Fulton Streets. Tucker’s wife had been to Macon to visit her sister, and she had fallen in love with the beautiful residences there surmounted by observatories. When she returned home, she told her husband she had to have one. Major Leyden and Mr. Bell both inquired as to how much extra an observatory would cost. When they were informed it would cost $200 extra, Mayor Leyden bowed out, but Bell decided upon an observatory replying to the doctor that “he would go him one better and place an observatory on his house that would cost $250!”

Contactor Rice named above handled the interior finishing work including the oak trim and marble mantles. He is also given credit for the home’s name – Calico House. He applied a thick coat of plaster over the outside walls. He originally intended to paint the walls brown, as was the custom of the day, but even in those early months of the war paint was scarce. Still, Rice managed to find dark red, light yellow, and pale blue paint.

Rice fell back on an earlier career when he was a book binder apprentice with publisher William Kay of Atlanta. He decided to marbleize the exterior surface of the walls like the way book publishers used to design the inside covers of books. The red, yellow, and pale blue colors intermingled with wave-like curves. It is said this occurred about the same time Atlanta dry goods stores began carrying a pattern of calico fabric in similar shades and presented a marbleized appearance. Someone remarked the home looked like calico, so the name stuck.

The photo below is the best I’ve seen of the Calico House where you can see the effect of the paint marbleizing. I’ve included a close view of one of the walls, too.

Not only did the owner of the Atlanta’s Calico House go to war serving as an aid in the Confederate Army to General Howell Cobb, the house also went to war serving as a beehive of activity for the war effort.

Overseen by Mary Jane Hulsey Bell, Bell’s wife, the home’s semi-basement floor was used to store clothing, food, and hospital supplies. Many of the city’s ladies used these supplies to ship out to various locations as they were needed.

As the war progressed the lower level rooms would be used for nursing sick and wounded.

Mrs. Bell and her children remained in Atlanta until her brother came to implore her to leave. It was on the night of July 10, 1864 Lieutenant Colonel W.H. Hulsey, of the Forty-second Georgia regiment of the Confederate Volunteers left his post at Kennesaw Mountain and rode 20 miles, swimming the Chattahoochee River both going and coming near Bolton to notify his sister the Yankees were moving on the city and she must leave before the bombardment began. Hulsey stayed long enough to secure the furniture and saw the family board the train for Elbert County. Amazingly, Hulsey was able to get back to his post at roll call the next morning with none of his command knowing he had ever left the night before.

It wasn’t the only time Lieutenant Colonel Hulsey managed to visit the Calico House during those days. The bombardment of Atlanta began on July 20, and by August 10th Marcus Bell managed to secure a 20-day furlough which he spent alone in his home while shells fell all around him. During some of this time Bell wrote a letter to his wife describing to her what was occurring all around him.

I’ve posted the entire contents of Bell’s letter in another post here if you would like to read it in it’s entirety.

During the war and for many years after the war the Calico House possessed a national reputation as being one of the few houses that survived the vandalism of Sherman’s torch, and the very first house in Atlanta occupied by federal officers when Sherman’s army entered the town. On September 6, 1864 General Slocum took possession of the home.

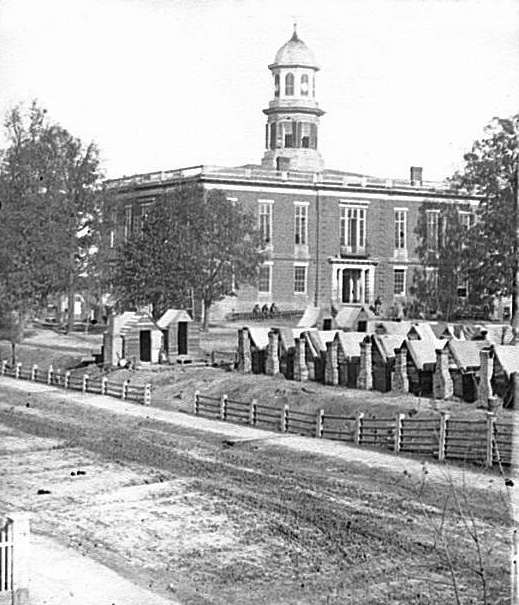

After the evacuation of Atlanta by General Hood, General Sherman pursued him to Lovejoy. In his memoirs Sherman says, “Upon reflection, I resolved not to attempt at that time a further pursuit of Hood’s army, but slowly and deliberately to move back, occupy Atlanta, enjoy a short period of rest, and to think well over the next step required in the progress of events, and on the 8th we rode into Atlanta, then occupied by the Twentieth corps (General Slocum). In the courthouse square we encamped a brigade, which had two of the finest bands of the army, and their music was to us all a source of infinite delight during our sojourn in the city. I took up my headquarters in the house of Judge Lyons, which stood opposite one corner of the courthouse square. Slocum having occupied the “Calico House.”

It was determined that for a very short time General Sherman did stay at the Calico House before he moved, and while there his staff would post his general orders on the north wall of the home’s main hallway in long rows. They remained glued to the walls for many years. Marcus Bell’s son, Piromus, finally witnessed a family servant scrape the orders from history many years later.

At some point during the occupation, Calico House was given over to Sherman’s engineering corps as well as the care and nursing of sick and wounded. For a month or so before federal troops left Atlanta the home was converted into a federal hospital and left by them in a most unwholesome condition. During Slocum’s occupancy of the house one of his aides had a pet colt which he stabled in one of the servant’s rooms. This, together with other acts of doubtful propriety, rendered the premises unfit for occupation by Mr. Bell and his family upon their return until after thorough disinfection and repairs.

The home was opened up to boarders including the Bells, but ran by Mrs. Susan Hoyle who held the lease. Many important borders lived there during Reconstruction including several members of the first legislature that met under the Reconstruction Constitution. Laura Stacy would be the second leaseholder still operating the home as a boarding house.

The Calico House was sold to J.T. Warnock in 1876. Warnock was an Atlanta transplant from Alabama. Soon after the home’s address would become 129 Courtland, and the Warnock family would be the last residents of the home.

Once Warnock died the property was sold in 1902 for $17,500. Quite a deal for a 50 x 190 foot lot shaded with oaks and magnolias plus the famed Calico House. The new owner was Asa G. Candler who would transfer the property to the Methodist Church for hospital purposes – Wesley Memorial Hospital to be exact.

The property would remain a hospital until 1922 when it would move to the Emory University Campus and become what we know today as Emory University Hospital.

The Calico House stood vacant for three years following the hospital’s move, and in 1925, the unique home that had witnessed so much history was demolished.

By 1930, the property at the corner of Auburn and Courtland was a parking lot, and that shouldn’t be a big surprise since parking lots seem to be what Atlanta does best.

Leave a Reply