A few years ago, I woke one morning realizing I had a few things to do that did not have anything to do with any of work goals. The long list included making appointments for others, finding paperwork for others, washing clothes for others, and planning a couple of projects I needed to finish for others.

I do not mind doing these things. I like to help, but more and more I was finding my day was full doing a list of things that did not have anything to do with a table of contents I need to organize, the attack I needed to make on a long list of topics to research, and chapters that were begging to be written.

It was just a normal day for me as I grew more frustrated by the minute, but this time my thoughts left my brain, moved down my arms and out my fingers to a Facebook status that said, “I wear too many hats that aren’t mine. Some are mine by misguided choice, some that are inherited, and some are foisted upon me. I’m going to stop. Take your hat and wear it yourself!

Later, while I was working out at the gym I thought about my status, and then my mind wandered to hats in general.

My first introduction to hats was at Greenbriar Mall west of Atlanta when I was five or six. Mother frequented Rich’s department store, once an Atlanta mainstay, quite often. She knew most of the clerks by name, and they knew her, too. I remember the layout so well I can close my eyes and walk around the store.

At the center of the store were the escalators with the bakery on one side as well as a hat counter. Every now and then if I caught my mother in the right mood she would give the clerk a smile, and they would let me sit down at the table and chair in front of a large mirror and try on a few hats.

I generally went for the flimsy, wide-brimmed pastel creations, but secretly I adored the veiled concoctions. It would take a few years, but at some point, I liked them because they were deliciously sexy. If you added in a pair of matching leather gloves that could be removed only by unbuttoning five or six covered buttons…oh my!

In another life I must have worn hats and gloves, and I mourn the fact I missed that era of fashion.

I turned away from my own hat desires to think about other hats.

What about hats in history?

In 2012 the Victoria and Albert Museum had an exhibit regarding hats which included, of course, hats belonging to former queens including Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II’s mother.

When we think of Queen Victoria we tend to think of a rather large aging lady in black as she spent the last several years of her life mourning the passing of her husband, Prince Albert, but for many years she dressed very colorfully including fancy bonnets. The collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum included a bonnet from the 1840s. It was a construction made of plaited horse hair and salmon pink ribbon. You can just make it out along the bottom half of this picture.

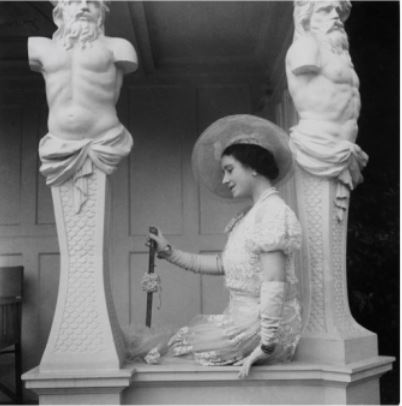

Another hat in the collection was the beige tulle and lace hat worn in the late thirties by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother. She wore the hat for a series of well-known photographs taken by Cecil Beaton on the grounds of Buckingham Palace such as the one I’ve placed below.

Turning towards American History the most iconic man’s hat would have to be Abraham Lincoln’s use of the top hat. Lincoln was already a tall man. It is said he was taller than most no matter where he went, so wearing a top hat was similar to a six-foot woman deciding to wear five-inch heels.

This hat is the one President Lincoln wore on the last night of his life, April 14, 1865. It is on display at the Smithsonian Institute.

My research indicates President Lincoln bought this hat from J.Y. Davis, a Washington hat maker. Notice the black silk band. Lincoln had this added to the hat in remembrance of his son William Wallace “Willie” Lincoln who died February 20, 1862, a victim of typhoid fever.

Following Lincoln’s assassination, the War Department took possession of the hat and other items left behind at Ford’s Theater. From there the hat became the property of the Patent Office and later was transferred to the Smithsonian where it has remained. In those days the employees of the Smithsonian Institute were instructed not to exhibit the hat and not to mention that it was there because of the furor it might cause in those early years following the President’s death.

The hat remained in a basement storage room for almost thirty years before it was finally displayed in 1893 when the Lincoln Memorial Association borrowed the top hat for an exhibition. Today, Lincoln’s top hat is one of the most popular artifacts of American History the museum owns.

Unfortunately, another iconic hat in American History is also connected to an assassination, the Kennedy assassination, and it was the iconic pill-box hat First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy made so famous going back to President Kennedy’s inauguration on January 20, 1961.

Later, the hat the First Lady wore at the inauguration was written about continuously including this mention that said:

[The hat was] a fawn-colored domed pillbox created by a then unknown twenty-nine-year-old named Roy Halston Frowick. The hat sat tilted toward the back, nearly doubled the size of her head, frankly, and creating a pretty contrast to her striking dark looks. She was nothing the country had ever seen. A fashionable, beautiful, and highly cultured First Lady, one who not only spoke fluent French but effortlessly shopped in Paris and New York. Across the country, women unanimously agreed: This young woman was their new fashion icon. For his part, Halston had no idea what was coming.

This photo I’ve placed below shows Jacqueline Kennedy wearing Halston’s beige pill box hat during the Kennedy inauguration on January 20, 1961. You can see four past, present, and future First Ladies side-by-side during John Kennedy’s inauguration. From the left we see Pat Nixon, Mamie Eisenhower, Lady Bird Johnson, and Jacqueline Kennedy.

Jacqueline Kennedy also wore a pillbox hat on November 22, 1963 in Dallas, Texas. Many sources say that the First Lady wore the pink suit with matching hat at the request of President Kennedy who loved to see her in the suit. For many years there was a question regarding the suit’s designer, but was finally solved by Coco Chanel’s biographer, Justine Picardie. She was able to provide the details that the garment was made by Chez Ninon using Chanel’s approved “line for line” system with authorized Chanel patterns and materials.

Pink had become a go-to color for many women in the 1950s around the time First Lady Mamie Eisenhower had a shade of pink named for her. See my article titled Mamie Pink – A Signature Color here.

The suit became a representation of the assassination as it was stained with President Kennedy’s blood. Mrs. Kennedy continued to wear the suit at the hospital and during the return trip to Washington, D.C. Mrs. Kennedy resisted repeated pleas by White House staff who asked her if she wanted to change, but she wouldn’t saying, “Oh, no … I want them to see what they have done to Jack.”

While she had continued to wear the suit stained with blood, she had removed her hat. William Manchester wrote in his book The Death of a President, “The Lincoln flew down the boulevard’s central lane; her pillbox hat, caught in an eddy of whipping wind, slid down over her forehead, and with a violent movement she yanked it off and flung it down. The hatpin tore out a hank of her own hair. She didn’t even feel the pain.”

The pink pillbox hat the First Lady wore on November 22, 1963 in Dallas is as iconic as the pink suit that became stained with her husband’s blood, but there is a mystery surrounding it. While we know exactly where the pink suit is stored at the National Archives in Maryland including the temperature of the room, the whereabouts of the pink pillbox hat is lost to history, and it remains missing to this day.

Mary Gallagher, the First Lady’s personal secretary, who accompanied her to Dallas confirms William Manchester’s account writing in her memoir titled My Life with Jacqueline Kennedy, “Somewhere inside the hospital [that fateful day in Dallas], the hat came off. “While standing there I was handed Jackie’s pillbox hat and couldn’t help noticing the strands of her hair beneath the hat pin. I could almost visualize her yanking it from her head.”

Though often pressed for more details regarding what had become of the hat, Mary Gallagher would not discuss it further. Some sources state it was Secret Service agent Clint Hill who gave Gallagher the hat. He was the agent who can be seen jumping on the back of the presidential limousine in a desperate attempt to protect the President and Mrs. Kennedy. Agent Hill has written three books regarding his time with the Kennedys including Five Days in November.

Other sources say the hat traveled aboard Air Force One back to Washington, D.C. in a paper bag on the lap of one of President Kennedy’s baggage handlers. Yet another source says the hat was given to a member of the White House police who was to pass the bag with the hat inside to Agent Hill, but it wound up in the hands of Agent Robert Foster who was the agent assigned to protect the Kennedy children. Foster would later state he took the bag to the Map Room on the ground floor of the White House. It was there where he opened the bag and saw it was Mrs. Kennedy’s hat. From there the whereabouts of the hat grows murky. There are various online mentions regarding who had the hat and when, but at some point, the hat went missing and remains so to this day.

We know that the suit, blouse, handbag, shoes and even the stockings Mrs. Kennedy wore in Dallas that day ended up at the National Archives and Records Administration complex in Maryland. It arrived in the same dressmaker’s box the suit was delivered to Mrs. Kennedy when it was brand new. Some say in the days following the assassination, Mrs. Kennedy’s mother, Janet Lee Auchincloss, placed the suit in the box and wrote “November 22nd 1963” on the top and stored it in her attic. Eventually the box was given to the National Archives in Maryland, together with an unsigned note bearing the Auchincloss letterhead stationery. The note read: “Jackie’s suit and bag worn Nov. 22, 1963”.

Eventually Mrs. Kennedy’s daughter, Caroline Kennedy, the current United States Ambassador to Australia, became the legal owner of the suit and presumably the missing hat. She signed a deed of gift to the National Archives for the suit and a situation was worked out where the suit would not be displayed until at least the year 2063. Some sources provide a later date.

Only a handful of people attached to the National Archives have seen the iconic pink suit, but I do wonder what become of the iconic pink pillbox hat.

If you enjoyed this article, you might be interested in reading A Little Pin Money regarding a little-known fund that was established for future First Ladies by Henry G. Freeman, Jr. Click through to see how some First Ladies have used the money.

Leave a Reply