In the early morning hours of April 10, 1949, Atlanta stayed awake for a farewell.

Streetcar Number 897—flat-wheeled, rattling, and well past its prime—rolled out of the Butler Street barn for the last time, carrying with it six decades of memory.

The Butler barn, the car barn for Atlanta’s streetcars, was used for storage and servicing. It was the system’s downtown home base and operations center and was located on the block bounded by Decatur, Butler streets, and Piedmont Avenue.

An early photo of the barn is shown below. The car on the extreme right is labeled as a River Line car.

Packed inside Number 897 were reporters, photographers, longtime riders, transit workers, and sentimental Atlantans who believed that some moments were too important to sleep through. By dawn, the city’s final electric streetcar would be gone forever, replaced almost immediately by buses and trackless trolleys. An era had quietly ended.

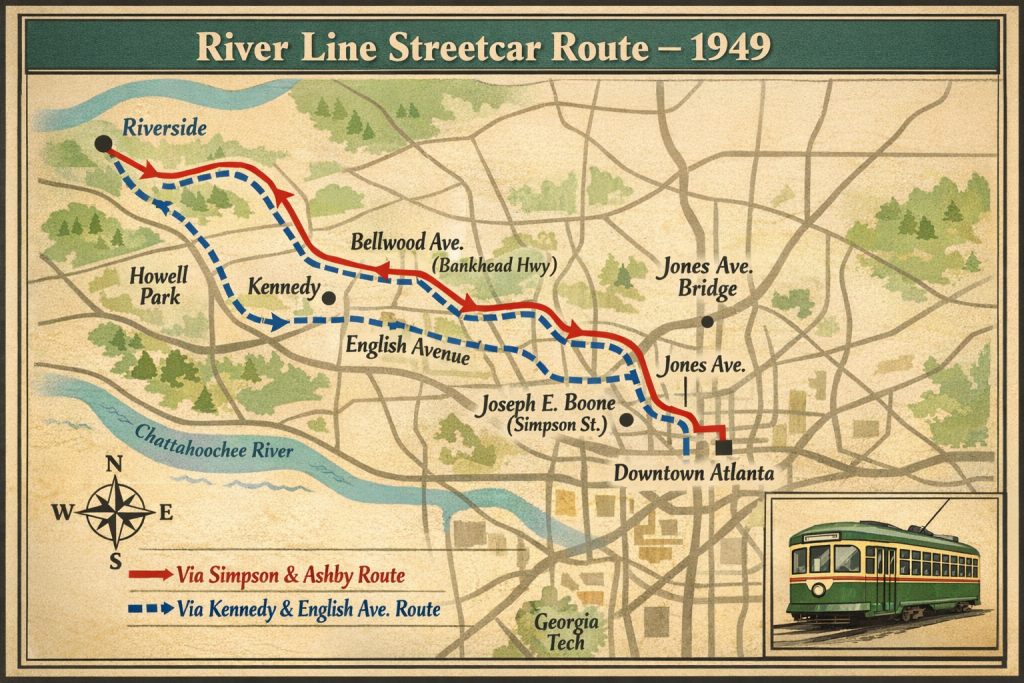

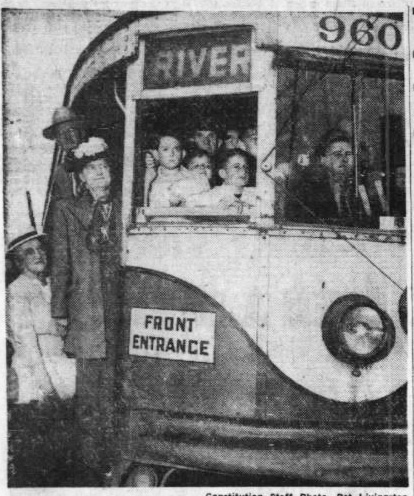

The last run took place on the River Line, the final remaining electric streetcar route in Atlanta illustrated below.

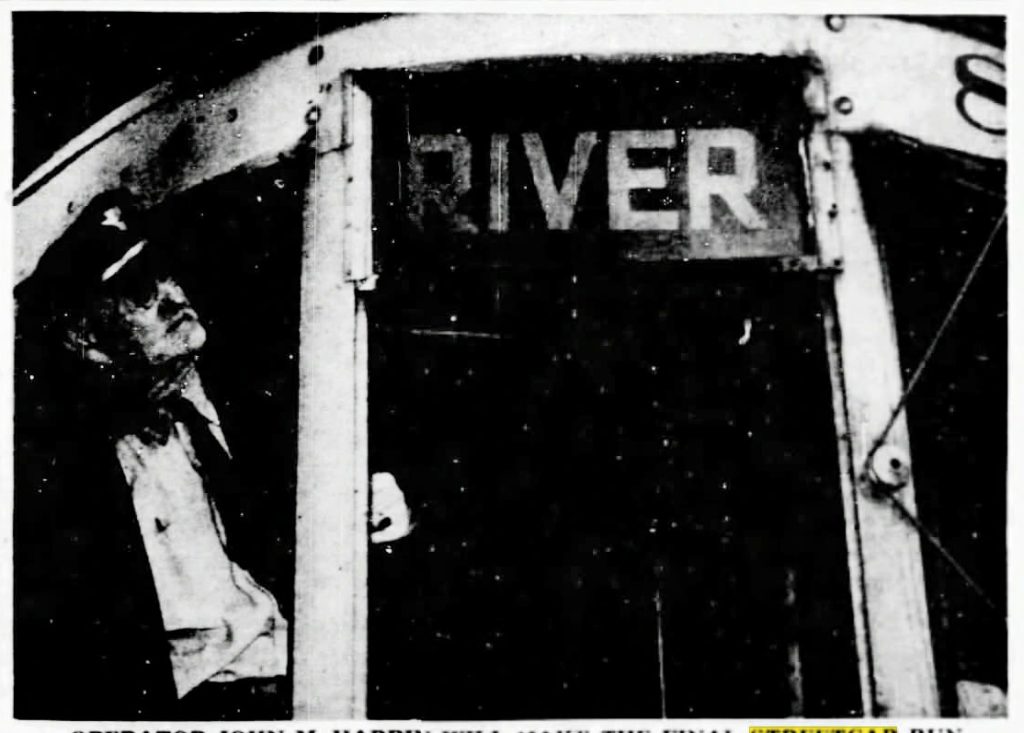

At the controls was John M. Harbin, a Georgia Power employee of 39 years and a River Line operator of five years. His presence was symbolic: Harbin had been born in June 1889, just weeks before Atlanta’s first electric streetcar made its debut and just three years before the River Line opened. In many ways, his life spanned the streetcar age itself.

Earlier that day between 2 and 5 p.m. free rides were given on the River Line cars for those going about their regular business and for some who wanted to participate in the historic day but didn’t want to stay up all night for the final run.

Some rode for the first time, some for the last. For some families, the last streetcar ride was a reunion with memory; for others, it was a quiet goodbye.

One nine-year-old named Clinton Storey rode the River Line with his grandfather, J.W. Storey, an operator who had spent 26 years on the route and would soon continue his work driving trackless trolleys. Another longtime operator, E.W. Moon, who had 32 years under his belt decided he would retire with the last streetcar route. Mr. and Mrs. Charles H. Vaughn took the final ride, too. They had met and fallen in love on the streetcar 25 years before.

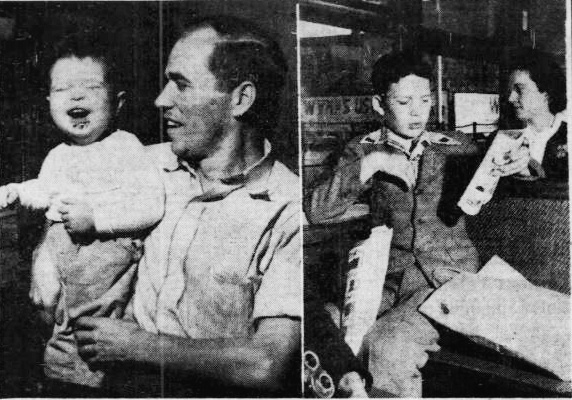

In the photo set below, you can see two-year-old Bernard L. Sullivan, Jr. and his father who lived on Hollywood Road (left) and thirteen-year-old James Worley of Austell. He was a regular passenger on the River Line and passed his time eating popcorn and reading a comic. His mom, Mrs. W.A. Worley, is seated near him.

For that last and final streetcar trip passengers began gathering at the Butler barn around 2 a.m. Number 897 left the barn twelve minutes behind schedule at 2:52 a.m. due to the crowds of well-wishers, photographers, and reporters with approximately 40 passengers. Among the passengers were Fulton County Commissioner Jim Aldredge and former commissioner Charlie Brown.

At Five Points the car stopped so photographers could take more pictures, and City Policeman David Smith, a former streetcar operator, took the controller from Harbin until they reached Broad Street.

As the car bumped and swayed along the route passengers kept themselves busy talking to each other and taking pictures. Souvenir hunters removed signs from the car’s walls as well as the brass handles from the wicker seats.

When Number 897 reached Riverside, a large crowd was waiting. More passengers boarded, there were more camera flashes, and the streetcar turned back toward town for its final, final return to the barn.

The return trip was noisy, informal, and slower as if Number 897 knew the significance of the trip back to the Butler barn and wanted the trip to take longer than usual.

A few of the younger passengers did take a little snooze. Pictured below are Ed and W.P. Woolf, III (left to right) sleeping while their father, W.P. Woolf, Jr. has his arm around them as the car jostled along.

As the streetcar clanged and swayed through downtown, passengers sang Auld Lang Syne and I’m Heading for the Last Roundup.

Several men took turns at the controller – operators, supervisors, and officials – each wanting a hand on the machine that had carried Atlanta for generations. The group included transportation supervisor M.F. Jones and manager John Gerson of Georgia Power.

Lieutenant Carl C. Heard, a member of the Atlanta Police recalled that he had been riding the River Line since 1910.

As the car passed an all-night diner, waitresses stepped onto the sidewalk to watch Number 897 representing a bit of history pass by. At the next corner a policeman solemnly waved hello and after the car had passed gave it another wave of goodbye.

Once Number 897 reached the Butler barn passengers disembarked to watch the car continue into the barn where it came to rest, 35 minutes behind schedule at 4:20 a.m.

Atlanta’s streetcar era came to a full and final stop.

Yet that final ride was only the closing scene of a much larger story.

Atlanta’s streetcar age began sixty years earlier, on August 23, 1889, when crowds lined Edgewood Avenue to watch the city’s first electric streetcar clang into motion. Before that moment, Atlanta’s public transportation consisted of a single horse-and-mule line running to West End. Electricity seemed mysterious—almost theatrical—and skeptics scoffed that such machines could never last.

They were wrong—at least for a time.

The electric streetcar quickly reshaped Atlanta. Tracks extended outward, and the city followed them. Neighborhoods like Inman Park, Grant Park, West End, and areas along Ponce de Leon Avenue grew because streetcars made daily travel possible. Atlanta expanded not randomly, but along steel rails that carried workers, shoppers, and families across town.

Social life followed the tracks as well. In an era before movies and radio, riding the open-air streetcar was entertainment all by itself. Families boarded for outings to Ponce de Leon Springs or Grant Park Springs. Adventurous riders paid a nickel for the famous “Nine-Mile Circuit,” a thrilling loop through Peachtree, Highland Avenue, Boulevard, and back downtown.

Streetcars carried wedding parties, picnic groups, and—perhaps most strikingly—funeral processions. In the early twentieth century, it was common to see special streetcars waiting outside a home in mourning. Coffins were placed across seat backs, families boarded according to custom, and conductors rang two bells to signal the motorman to proceed. The streetcar carried the living and the dead alike, faithfully serving every stage of life.

By the early twentieth century, streetcars were inseparable from Atlanta’s identity. They clanged and jolted, swayed and rattled, and their seats were hard—but they got people where they needed to go. For decades, they were the city’s circulatory system.

Progress, however, is rarely sentimental.

By the 1940s, rubber-tired buses and trackless trolleys were faster, quieter, and more flexible than rail-bound cars. Tracks required maintenance; streetcars could not easily reroute. What had once been modern now seemed outdated. Georgia Power gradually replaced electric rail lines, and by the time Number 897 took her final run only the River Line remained.

On April 10, 1949, that final line disappeared.

When Number 897 fell silent, Atlanta did not pause. Buses and trolleys took over almost immediately. Traffic moved on. The city kept growing.

But something intangible was lost—the rhythm of steel wheels on rails, the clang of bells echoing through neighborhoods, the way Atlanta once grew by following the streetcar’s path.

The skeptics of 1889 were right, eventually. The streetcar did not stay.

It simply stayed long enough to build a city.

Leave a Reply