From time to time a friend will ask me about my writing.

Questions concerning what I’m working on, what topics I’m researching, or what to expect next with the blogs or my column with the Douglas County Sentinel.

It’s nice to have friends and family who are interested.

Last week I advised I was working on Woodrow Wilson’s time in Atlanta.

My friend was surprised and immediately said, “Wilson was in Atlanta????”

Yes! Woodrow Wilson spent a year in Atlanta after he finished law school. In fact, he arrived in the city without an official stamp of approval from the bar. He soon took the bar exam though…and passed.

In a letter to Charles Talcott, a classmate and friend at Princeton on September 22, 1881 Woodrow Wilson gave his reasons for wanting to settle in Atlanta, Georgia after school.

Wilson said, After innumerable hesitations as to a place of settlement, I have at length fixed upon Atlanta, Georgia. It more than any other southern city offers all the advantages of business activity and enterprise. Its growth during late years has been wonderful…And then, too, there seem to me to be many strong reasons for remaining in the South. I am familiar with southern life and manners for one thing – and of course a man’s mind may be expected to grow most freely in his native air. Besides, there is much gained in growing up with the section of country in which one’s home is situate, and the South has really just begun to grow industrially. After standing still, under slavery, for half a century, she is now becoming roused to a new work and waking to a new life. There appear to be no limits to the possibilities of her development; and I think to grow up with a new section is no small advantage to one who seeks to gain position and influence.

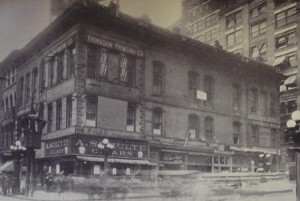

Upon arriving in the city of Atlanta Wilson set up shop partnering with Edward Ireland Renick, a former classmate. Renick already had an office at 48 Marietta Street which was then known as Concordia Hall…later the Ivan Allen Marshall Building at the the corner of Marietta and Forsyth Streets.

Their office was on the second floor in the back.

Their office was on the second floor in the back.

The building was demolished in the 1960s to make way for the First Federal Savings and Loan building.

Renick was living in the home of Mrs. J. Reid Boylston, a widow, who lived at 344 Peachtree Street on the west side of the street a little north of Pine Street. Wilson moved in as well and was soon attending the First Presbyterian Church of Atlanta, too.

In his book, Atlanta and Environs, Franklin Garrett recalls the inauguration of Governor McDaniel, and Wilson’s take on the whole scene advising Governor Alexander H. Stephens had died and James S. Boynton of Griffin, President of the Senate, succeeded to the office until a special election could be held. The Democratic Party met in April. Henry D. McDaniel, a banker, railroad director, member of the House from Walton County was nominated.

Garrett further advised that a young Woodrow Wilson witnessed the crowd assembling for the inauguration of Governor McDaniel from his office window. The next day Wilson wrote a friend in Berlin:

Governor McDaniel was inaugurated yesterday. As I sat here at my desk I could see from my office windows, which look upon the principal entrance of the big, ugly building which serves near Atlanta as a temporary capitol, the mixed crowds going in to secure seats in the galleries of the House of Representatives at the inauguration ceremonies.

They were probably not much entertained though they may have been considerably diverted, for our new governor cannot talk. He stutters most painfully, making quite astonishing struggles for utterance.

A Tennessean wag expressed great commiseration to Georgia in her poverty of sound candidate material, and offered to send some over from Tennessee for the relief of a state which was about to replace a governor who could not walk [Stephens] with a governor who could not talk.

McDaniel is sound enough in other respects, however, not remarkable except for honesty – always remarkable in a latter-day politician – but steady and sensible, all the harder worker, perhaps because he can’t talk….

Apparently Georgia didn’t mind a little speech impediment since they elected McDaniel in his own right in 1884.

Wilson gave Atlanta up in 1883 and enrolled at John Hopkins, but before leaving the city Wilson wrote, Here the chief end of man is certainly to make money, and money cannot be made except by the most vulgar methods. The studious man is pronounced impractical and is suspected as a visionary. Atlanta students of specialties – except such practical specialties as carpentering, for instance – are classed together as mere ornamental furniture in the intellectual world – curious perhaps and pretty enough, but of very little use and no mercantile value.

Interesting thoughts from from our 28th President about the city of my birth.

Leave a Reply