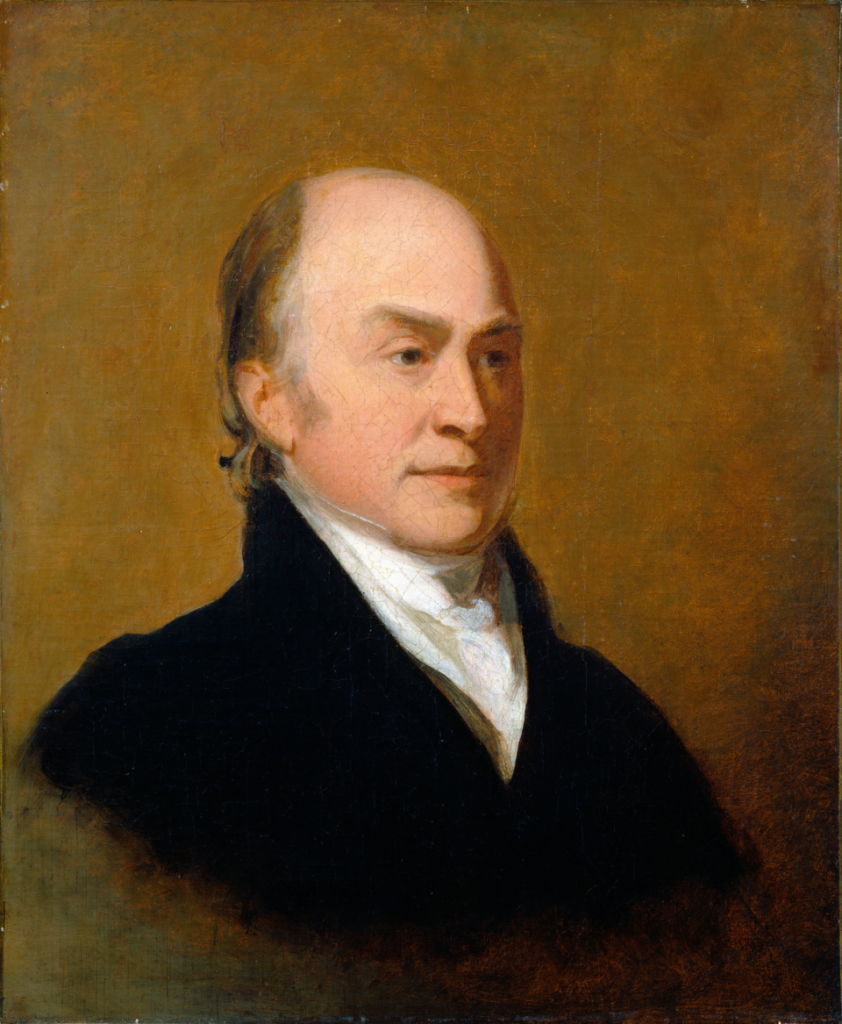

When James Monroe addressed Congress in December 1823, he could not have known that a few paragraphs embedded in an annual message would shape American foreign policy for more than two centuries. Yet the Monroe Doctrine—born in an age of sailing ships, European empires, and newly independent republics—continues to surface whenever the United States confronts instability or foreign influence in the Western Hemisphere.

Often dismissed as a relic of early American diplomacy, the Monroe Doctrine instead established a durable mindset: that events in the Americas are not distant concerns but matters of U.S. national security. Understanding why it was written, how it evolved, and why it is still invoked helps explain its enduring relevance.

What the Monroe Doctrine Says

On December 2, 1823, President Monroe delivered his annual message to Congress. Within it was a foreign policy declaration that soon became known as the Monroe Doctrine. Its core principles were straightforward:

- The Western Hemisphere was closed to future European colonization.

- Any attempt by European powers to interfere in the affairs of independent American nations would be viewed as hostile to the United States.

- The United States would not involve itself in European wars or internal political disputes.

- Existing European colonies would be left undisturbed, but expansion or recolonization would be opposed.

Together, these points asserted that the Americas constituted a political sphere distinct from Europe—an extraordinary claim for a young nation with limited military power.

Why It Was Necessary in 1823

The doctrine emerged during a moment of upheaval. In the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, Spain and Portugal were weakened, and much of Latin America had recently gained independence. American leaders feared that Europe’s conservative monarchies might attempt to reclaim those territories.

There were practical concerns as well. Recolonization threatened republican self-government, endangered U.S. security, and risked reinstating restrictive trade systems that would block American commerce. Although the United States lacked the naval strength to enforce the doctrine alone, British support—motivated by its own commercial interests—gave the policy credibility.

How the Doctrine Evolved

Initially ignored by Europe, the Monroe Doctrine gained force as American power expanded over time. It became a justification for increasingly assertive actions in the hemisphere.

In the 1860s, when France installed a European monarch in Mexico, U.S. diplomatic pressure helped force a French withdrawal. In 1904, Theodore Roosevelt dramatically expanded the doctrine with the Roosevelt Corollary, asserting that the United States had the right to intervene in Latin American nations to prevent European involvement. This reinterpretation justified U.S. military and political interventions across the region, including in Haiti and Nicaragua.

During the Cold War, the doctrine merged with anti-communist containment policy. The most dramatic example came during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the United States demanded the removal of Soviet missiles from Cuba. Similar logic was used to justify U.S. involvement in Guatemala in 1954 and Chile in 1973, where governments were overthrown amid fears of communist influence.

Why the Doctrine Still Matters

Though nearly two centuries old, the Monroe Doctrine continues to shape American strategic thinking.

Foreign influence remains a central concern. Where the original doctrine targeted European empires, modern applications focus on ideological, economic, and military involvement by outside powers—particularly Russia and China—in Latin America.

Transnational threats also play a role. Drug trafficking, human trafficking, and organized crime operate across borders and are often framed as hemispheric security issues tied to U.S. interests. Policymakers continue to justify partnerships and interventions using language rooted in Monroe-era thinking.

Economic and strategic priorities persist as well. From protecting the Panama Canal to opposing foreign military footholds in the region, the doctrine’s underlying logic still informs U.S. diplomacy and defense planning.

An Enduring—and Contested—Legacy

The Monroe Doctrine began as a defensive warning against European imperialism. Over time, it evolved—through the Roosevelt Corollary, Cold War interventions, and modern reinterpretations—into a broad framework for U.S. involvement in the Western Hemisphere.

It remains politically potent:

- As a justification for American action,

- As a source of skepticism and resentment in Latin America,

- And as a lens through which modern threats are interpreted as security concerns.

The Monroe Doctrine is often reduced to a slogan, stripped of its complexity. My aim here is not to defend or condemn its use, but to place it in historical context—how it began, how it changed, and why it continues to be invoked. Whether viewed as protection, overreach, or something in between, it remains a powerful tool for understanding how the United States defines its role in the Americas.

History reminds us that doctrines do not disappear. They adapt—reshaped by the fears, ambitions, and debates of each generation.

Leave a Reply